Stephen G. Breyer ’64 has served as an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court since 1994. Hewas born and raised in California and attended Lowell High School in the San Francisco Bay area, where he competed in debating tournaments. He received his A.B. from Stanford in 1959 and studied economics and philosophy at Oxford University on a Marshall Scholarship.

After graduating from Harvard Law School, where he was articles editor of the Law Review, he clerked for Justice Arthur Goldberg during the Supreme Court 1964-65 term, helping Goldberg write his opinion in Griswold v. Connecticut, the landmark right-to-privacy case. Following a stint in the Justice Department’s antitrust division, he joined the faculty of HLS, where he taught full time from 1967 to 1980, with interruptions for public service. He was an assistant to Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox and later chief counsel to the Senate Judiciary Committee.

In 1980, President Carter appointed Breyer to a seat on the United States Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit, where he served–including four years as chief judge–until President Clinton elevated him to the Supreme Court in 1994.

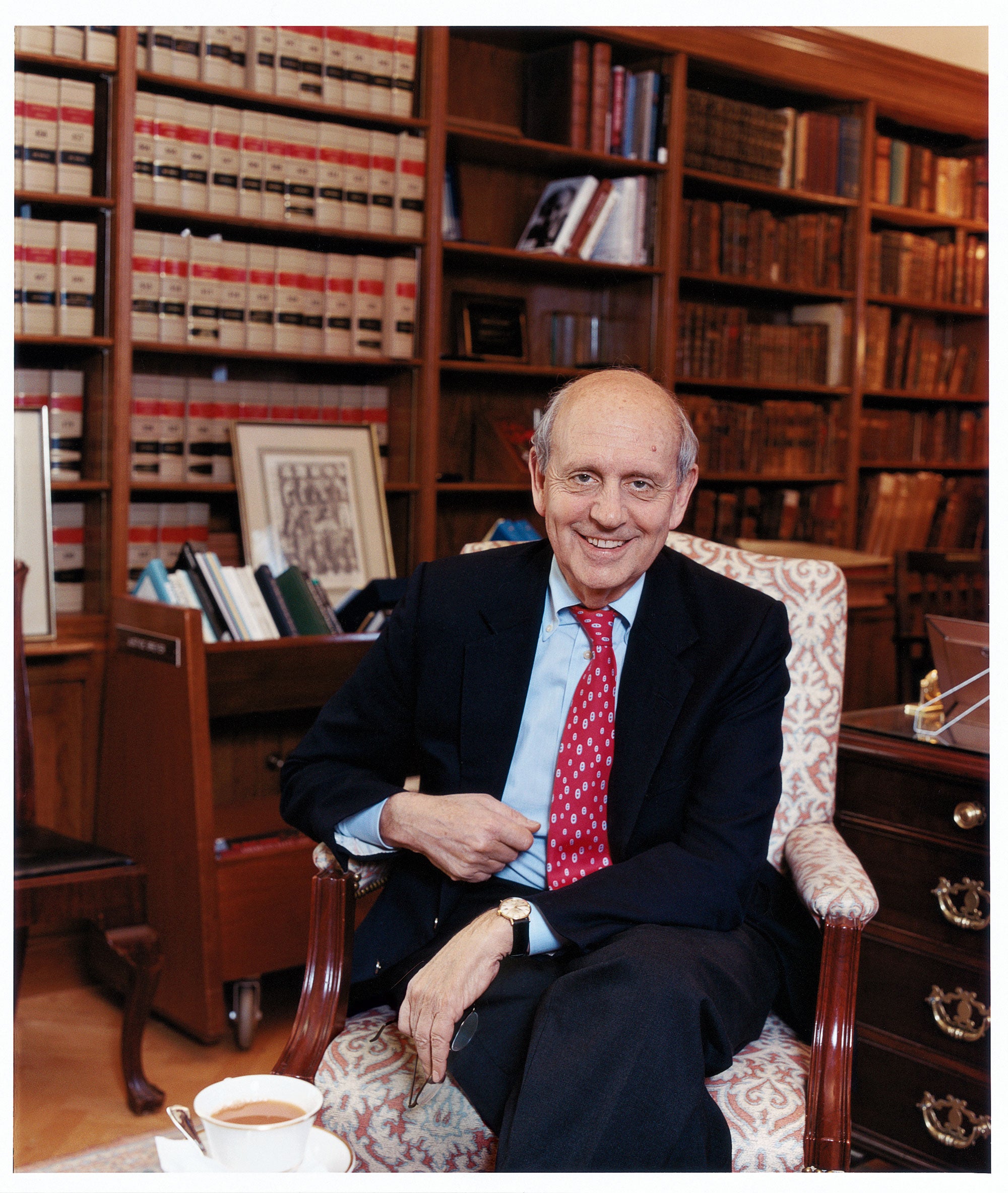

Recently, he welcomed Robb London ’86, editor of the Bulletin, and Michael Armini, HLS director of communications, into his chambers. After serving tea and throwing logs into a fireplace near Felix Frankfurter’s chair, Breyer discussed a range of issues, and also his new book, “Active Liberty: Interpreting Our Democratic Constitution,” in which he argues that judges should pay more attention to the framers’ purpose of maximizing citizen participation in the democratic process, and criticizes the “originalist” view of constitutional interpretation.

Q: Is there a typical day in the life of an associate justice of the Supreme Court?

A: The working life of the Supreme Court justice is reading briefs and writing opinions. So a lot of it is spent here at the desk, with my word processor. I usually say to students what I told my son when he was growing up: If you do homework very well, you will get a job where you can do homework the rest of your life.

We hear about 80 cases [each year] culled from close to 8,000 applications. Our standard for hearing a case is whether there is a need for a uniform rule of federal law. And there’s most likely to be that need if the lower courts come to different conclusions on the same question of federal law. If they all come to the same conclusion, there is less likely to be a need for us. Justice Jackson said once that we’re not final because we are infallible, we are infallible because we are final.

So we’re there when other parts of the system come to different conclusions. Now, that isn’t 100 percent of our criteria, but it is the main one. So out of those 8,000 cases–that’s about 150 a week–the law clerks in the building will write memos. There are about 30 law clerks, and they each write about five memos. And I’ll get a long stack, and I go through them to figure out what the issue is, primarily. Then almost every week we have a conference, and we will discuss those cases that any one of us wants discussed. And if there are four votes to grant the petition for a hearing, it’s granted. We can consider the same petition two or three times, if anyone wants to reconsider it. I talk to my law clerks quite a lot.

And the other part is hearing the cases, which is, as I say, reading large sets of briefs and listening to an hour’s worth of oral argument. And oral arguments are held in seven sessions across the year, and we’re all prepared–we’ve read the briefs, we’ve had our law clerks write memos, we’ve had a couple of discussions with our clerks. And then the nine of us are there, and the lawyers basically answer our questions for an hour. And that’s not an easy thing for a lawyer.

Then we have conference. When we conference the cases each week, we all are in the conference room by ourselves. And we go around the table in order.

The secret to the conference is, people say what they really think. They’re giving their true reasons for deciding a case this way or that way. And as long as it’s a very honest discussion, which it is, and people are talking about the reasons that are important to them, it’s possible for it to be productive. As soon as it becomes a debate, it’s not productive, because anyone can think of some argument that he thinks is better than somebody else’s argument. What is going to help is listening to the other person and trying to see what is of interest and concern to that other person, and then responding, appropriately.

So there is discussion. We have a tentative vote. And as a result of that vote, the opinion will be assigned to one of us. And then we start drafting. That’s why I say it’s reading, it’s writing. And that’s where my law clerks will do a long memo or a draft. I will then take the briefs, read them and write my own draft. Then the law clerk will redo it. Usually I have to write my own draft from scratch, basically two or three times. And then we go back and forth and the drafts circulate, and I hope they join. If I get five votes, that’s the majority. People can write dissents or concurrences. When everybody’s finished writing or joining, the case comes down.

Q: How often do you go into oral argument genuinely uncertain about which way you’re going to go?

A: You’re rarely uncertain. As soon as I read a question, I have a view. But the fact is, at the earlier stages of the case, although I have a view, I’m very open to changing my mind. Over time you become less and less willing to change your mind. For example, the old joke is that you read the petitioner’s brief, you say they’re right. You read the respondent’s brief, you say they’re right. Then somebody says they can’t both be right, and you say, “You’re right.”

So I go into oral argument almost always with a view. But quite often I’ll change it. How often? Maybe15 or 20 percent of the time. But more often than actually changing the outcome, it might change what I think is important, how to characterize it, what the arguments are. And sometimes, really, it will be radically different.

Q: Is your new book, “Active Liberty,” a deliberate rejoinder to Justice Scalia’s [“A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law” (1997)]?

A: No, it’s not a deliberate rejoinder. It is what I wanted to do as a judge. I’ve been a judge for 25 years. And I’ve been a judge on this Court for 11 years. And people sometimes want to know–I myself wanted to know–how is being a judge on this Court different from being an appeals court judge? Being an appeals court judge is totally different from being a trial court judge. They’re simply different jobs. And is the Supreme Court different again? I think it is, in a way. But the difference arises out of the fact that, unlike an appeals court, we have a steady diet of constitutional cases.

And then I think it inevitably forces a judge on this Court to try to see the Constitution as a whole. What does that mean? That you begin to take a view of it. And of course, I was curious if I could put down on paper what had been emerging as a view of the Constitution that I think informs my opinions. I’m interested in that, because I’d like to be reasonably consistent. I don’t know if I’m being consistent. I’m deciding each case as it comes along.

I was interested to go back, to see what I thought about the Constitution as a whole. And it does turn out to be a different view than Justice Scalia had. And I tried to put some of that down in this book. Many people have held similar views–but it’s an effort to put down on paper something of what I’d call a more traditional view of the Constitution. And if you are an originalist, that’s inconsistent with the way I see the job of interpreting the Constitution, and in this book I discuss that.

The [book] is not directly aimed at anyone. If there’s a direct aim, it’s to try to explain to people who aren’t judges and some who aren’t even lawyers, but certainly to law students, that from my perspective as a judge of this Court, the document that we interpret, the Constitution, is primarily concerned with setting up a democratic form of government. Not exclusively, but primarily. And there are other important parts as well, but that’s a very important part that people sometimes don’t notice, because it’s as obvious as the nose on your face.

I’ve become more and more convinced that if people don’t take advantage of those democratic institutions and participate in the democratic process, the Constitution won’t work very well. Because that’s what it foresees: participation in the democratic process.

Q: How are law schools doing today in terms of training tomorrow’s judges?

A: Well, the law schools are doing what they always did. They do it very well. [But] the law is so fractionated now. It’s terribly easy now for a graduate of a law school [to go] directly into a firm and spend his entire life learning nothing but the latest regulations of the bank regulators. That’s a pity, because it’s too narrow.

The great advantage of law always was that you could be a generalist. You have to specialize, but also you could be a generalist. And in particular, it’s supposed to give you enough time to participate in the life of a community. And it becomes harder to have a life that is satisfactory in terms of family, community and work. Law schools can’t easily control what law firms do, but they can encourage. The forms of encouragement are many–public service scholarships, forums where they can bring up issues with people in firms, participation by law professors in professional associations, like the ABA.

So I’d say the challenge for the law schools is the same as the challenge for every one of us, and that is how to prevent specialization from turning into balkanization. Can the law schools help? Probably, but only a little.

One of the courses I took in law school that made a tremendous impression on me was Agency with Professor Louis Loss and Professor Austin Wakeman Scott. Agency taught the notion that a lawyer is a fiduciary. A fiduciary does not get his reward in life from the amount of money that he earns. He gets it by practicing the profession for the advantage of someone else. If you see law as a path toward making a fortune, I would say that’s unfortunate. That isn’t the job of a lawyer. And the more that people think it is, not only is it harder to keep that general interest in the community, but the more they’re in a world they find unsatisfactory.

Q: Why is it controversial when a justice of the Supreme Court looks to foreign law for guidance?

A: Well, I think it’s controversial because the two cases in which that became an issue happen to be cases involving controversial subjects–the death penalty and the rights of homosexuals, gay rights.

By and large, I think it is not controversial. References to cases elsewhere are never binding. We’re interpreting the American Constitution, American law. And foreign case law is there by way of reference. It may show support or the opposite of what you should do. It’s like referring to a treatise or like referring to a professor’s work. But the more it refers to the values of people abroad, the more it seems as if the object of the reference is to promote values, the more controversial it is. The more the purpose of the reference is to look at how other people solve similar problems, the less controversial it is. And that’s as it should be.

Consider, for example, the question of how Israel deals with the problems of terrorism and security. Isn’t that something you’d like to know? Not that it binds us, but you’d just like to know what’s possible in trying to balance those different objectives.

More and more of the cases in front of us involve questions of foreign law. And we have to be able to look to others. The real obstacle is not posed by politicians. It’s ignorance, when we don’t know what the source is, and the lawyers who must tell us may themselves not be sufficiently familiar with the foreign sources, because when they went to law school, the professors were themselves not that interested.

We’re getting more and more briefs filed by the European Union, by Japan, France, Germany. Those briefs help.

Q: The death penalty is one place where we tend to differ with many foreign countries. What’s it like to approach a death-penalty case?

A: I didn’t have any death cases at all when I was in the 1st Circuit. [Here] there are quite a few. And when one comes up just prior to an execution, we’ll all consider the case, almost always. And there’s a system for doing so, but although it’s routine, it’s never routine, because from the beginning and continuously, one is fully aware of what turns on the decision. So it’s approached with caution and care.

Q: Does it affect you on a personal level?

A: These cases affect a lot of people.

My wife is a clinical psychologist. She works at Dana Farber. And she’s working with children, and many of them and their parents have terrible problems. So there are people in other professions who deal with the most difficult human problems on a daily basis. And I think here, as in all those jobs, you don’t ever become immune to or unaware of the consequence of what you’re doing. You take the job seriously and do your best.

Q: Quite a few states have judges who are elected. It sounds like that’s not something you would support.

A: No, the grave concern with the elected judge today is campaign contributions. A student of mine became chief justice of Texas. He told me he had to collect several million dollars in campaign contributions. Now, that is a debilitating influence, and at the very minimum it produces an appearance of justice for sale. It’s a very, very bad thing. But ultimately it has to be up to the people of the state to decide what to do.

Q: Of your predecessors on the bench and on this Court, whom do you admire the most and why?

A: I admire different ones at different times. I admire Brandeis a lot because he’d go into things in detail. He tried to be very fair-minded. He considered laws as a series of problems aimed at trying to produce a better system that worked better for people. He was practical. And he was basically a defender of civil liberties, but with care and caution in the analysis.