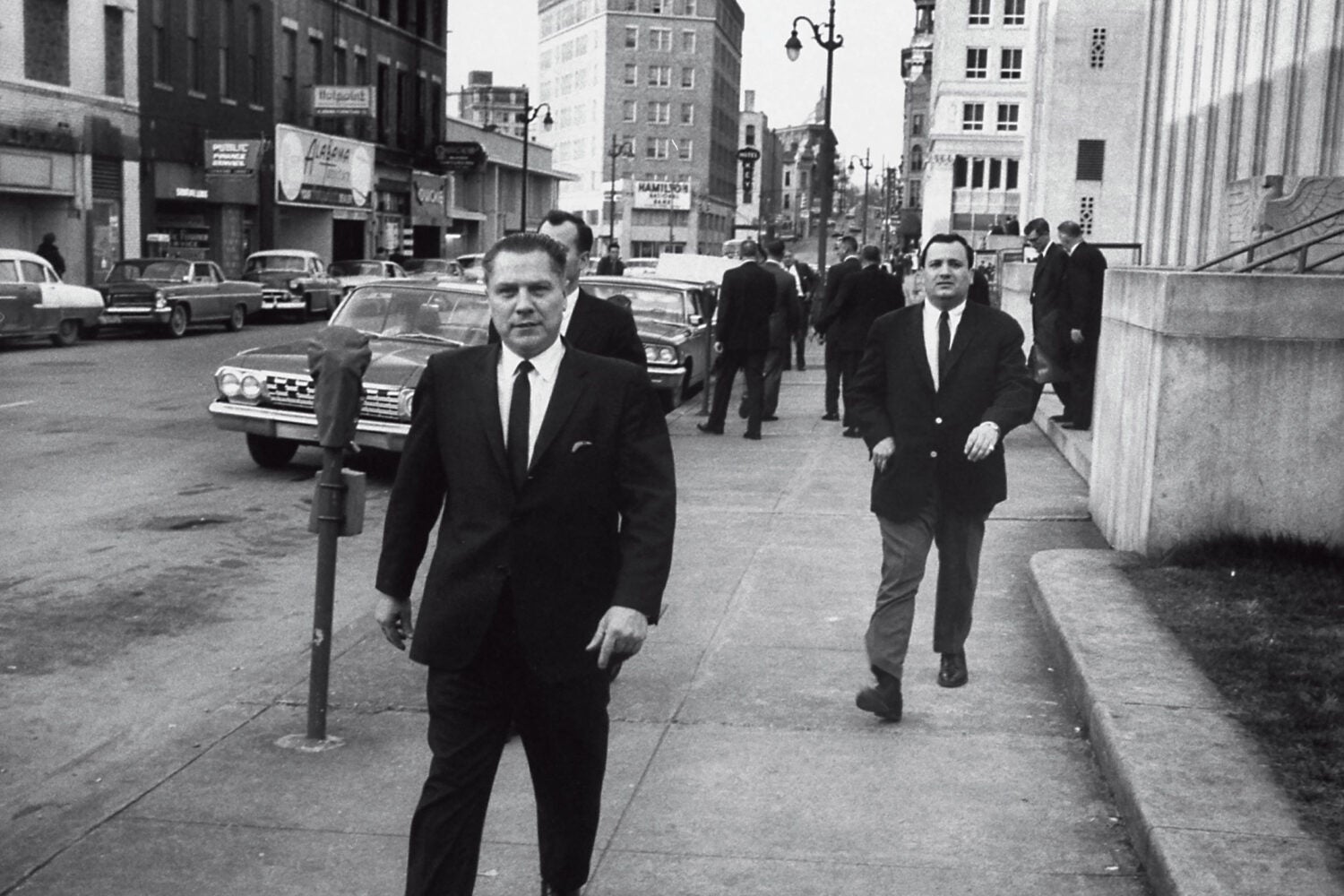

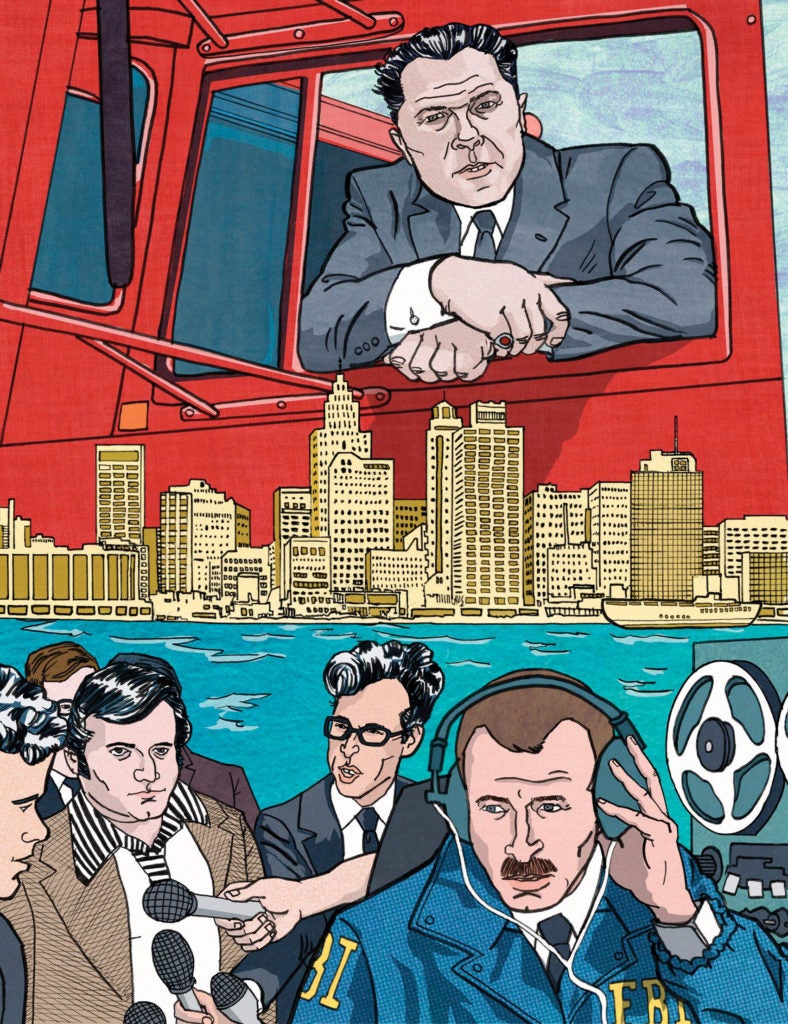

It’s one of the most notorious unsolved crimes in American history: the mysterious disappearance, in July 1975, of Jimmy Hoffa, charismatic former president of the powerful Teamsters union, beloved by union members, and a seminal leader in the American labor movement. Hoffa’s tight relationship with the Mafia became an obsession for Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, who in the 1960s created a “Get Hoffa” team that resulted in Hoffa’s five-year prison stint. Four years after being pardoned by President Richard Nixon, Hoffa disappeared. Though he was declared legally dead in 1982, his body has never been found, and his exact fate remains unknown despite vigorous efforts to uncover the truth by law enforcement, journalists, and filmmakers.

Goldsmith had one request of his stepfather: “you have to tell me the truth.” That was complicated.

Seven years ago, Jack Goldsmith, Harvard Law School professor and a former assistant attorney general in the George W. Bush administration, set out to solve the case. His motives were deeply personal: For 38 years the spotlight of suspicion had shone on Hoffa’s closest confidant, Charles “Chuckie” O’Brien, a rough-hewn union man with close Mafia ties and the inspiration for the consigliere character Tom Hagen in “The Godfather.” O’Brien, who has always proclaimed his innocence, is Goldsmith’s stepfather. If he was clean—and Goldsmith had no idea if he was—Goldsmith hoped to clear his name. It was, in many ways, an act of penance: In order to further his own legal career, Goldsmith for 20 years had refused any contact with his loving and supportive stepfather.

With the aid of his stepfather’s inside knowledge, Goldsmith was certain he would succeed where others failed. Now, after conducting dozens of interviews with FBI agents and other Hoffa experts, poring over thousands of pages of government documents including transcripts of illegal wiretaps, and spending thousands of hours in often-painful conversations with O’Brien, Goldsmith has written “In Hoffa’s Shadow: A Stepfather, a Disappearance in Detroit, and My Search for the Truth.” Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux this fall, the memoir-cum-whodunit has garnered rave reviews for its historical relevance, exquisite writing, and raw depiction of the complex relationship between Goldsmith and his stepfather. Bill Buford, former fiction editor of The New Yorker, calls it a “thrilling, unputdownable story that takes on big subjects—injustice, love, loss, truth, power, murder—and addresses them in sentences of beauty and clarity informed by deep thought and feeling.” HLS Professor Lawrence Lessig says, “This book will make you weep, repeatedly, for the injustice, and for the love.”

Goldsmith pulls no punches, especially when revealing his stepfather’s flaws, and his own.

“In Hoffa’s Shadow” is peopled by the parade of famous and sometimes-treacherous characters who touched O’Brien’s life: Robert F. Kennedy, Richard Nixon, major mob figures, federal prosecutors. In Goldsmith’s examination of some of the darkest aspects of 20th-century America—the violent history of organized crime, the growth of the surveillance state, the rise and decline of organized labor—he pulls no punches, especially when revealing his stepfather’s flaws, and his own. The most unusual aspect of “In Hoffa’s Shadow” is that it was born through a complex cat-and-mouse game between two men who love each other but have very different concepts of truth. “I had no expectations about what would happen when I started out on this book,” says Goldsmith in an interview with the Harvard Law Bulletin. “I really thought [Chuckie] had been given a bad shake.” Goldsmith believed that by pressing his stepfather for what he knew, and exhaustively analyzing all the evidence, he could at least “give him a fairer shake. That was my main ambition.” But he reveals a more wrenching motivation. “I wanted to make up for my past mistreatment of him,” Goldsmith admits. “I wanted to give him a fair shake because he had had terrible luck his whole life in terms of not just what happened to him with [Hoffa’s] disappearance but just about everything.”

While working on the book drew the two men closer than they’d ever been, “I had no idea what an ordeal it was going to be,” Goldsmith says. He had one request of his stepfather: “You have to tell me the truth.” It turned out to be a complicated request.

“Chuckie was committed to Omertà, I was committed to its opposite, but we were both committed to each other. . . . He was always on guard for forbidden topics, and was brilliant, when he wanted to be, at resisting my probes.”

—In Hoffa’s Shadow

For O’Brien, born in Detroit to a Sicilian mother with close mob ties, unvarnished truth-telling takes a back seat to Omertà, the Sicilian code of silence. Omertà “really ordered the way Chuckie looked at the world,” says Goldsmith. “It was at the core of his identity because it constituted honor and loyalty, and I think those are the two things he cares about most.” As Goldsmith pushed him to share what he knew, his stepfather’s reluctance to be forthright “wasn’t because he feared having to go to [witness protection] or he feared death,” says Goldsmith. “I think it was [because he thought] it wasn’t the right thing to do.” Things that his stepfather didn’t want to talk about—including exactly how much he knew about Hoffa’s fate—“were the things that I wanted to talk about most,” he says.

While he found it frustrating, “Over time, in a kind of perverse way, I grew to admire this,” says Goldsmith, “not because I admire what it represents in the organized crime world but because it was a principle that [Chuckie] really gave everything for in his life, and that he held on to for his entire life.”

“Chuckie was my third father, and my best.”

—In Hoffa’s Shadow

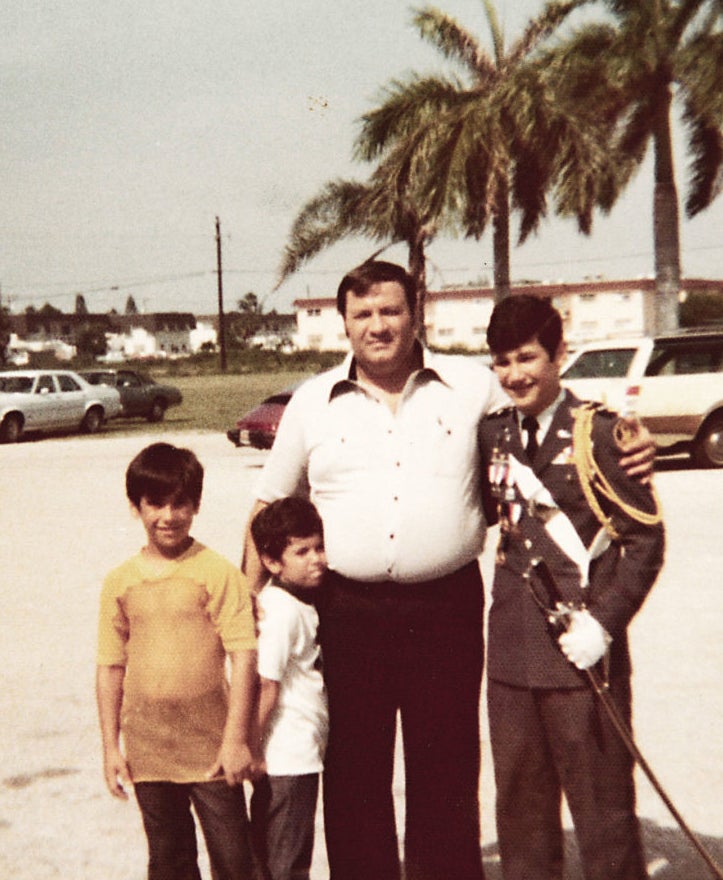

Before Chuckie O’Brien married Goldsmith’s mother, in 1975, Goldsmith had no consistent male figure in his life. “I was doing OK, but I wasn’t doing great,” recalls Goldsmith, whose birth father abandoned his family, and whose first stepfather, “distant but stern,” divorced his mother when Goldsmith was 11. His new stepfather was a steady force, physically strong and, “in a strange way, even though it’s not true of many aspects of his life, a morally strong person. I mean he had a strong sense of right and wrong.” Because of him, says Goldsmith, “I grew as a person and kind of on the right path in a way I’m sure I never would have.”

O’Brien’s unconditional love was all the more remarkable because of the intense stress he faced: Shortly after O’Brien entered Goldsmith’s life, Hoffa disappeared. The FBI quickly decided O’Brien was involved and leaked its suspicions to the media to pressure him into cooperating with the investigation. “And yet despite all that stuff going on, I remember those five or six years as a time of happiness and stability, strangely enough, and that’s all due to him,” Goldsmith says. In return, Goldsmith loved and admired his stepfather, “and of course that means that I came to admire the things he admired. I admired the Teamsters. I kind of had a sanguine attitude about what I understood as a teenager about the Mafia.” In fact, as a teen, Goldsmith knew Mafia boss Anthony Provenzano—who looms large throughout the Hoffa case—as the generous “Uncle Tony” who gave him and his brothers a pool table, and Goldsmith was treated to lunch by Anthony Giacalone, “part of my new family.” Only later did Goldsmith learn of Giacalone’s legendary propensity for violence and suspected role as mastermind in Hoffa’s case.

“I renounced Chuckie out of apprehension about his impact on my life and my career. . . Chuckie had done nothing affirmatively to hurt me, and indeed had only ever shown me love.”

—In Hoffa’s Shadow

In college, Goldsmith’s views shifted as he began reading about the mob and Hoffa’s disappearance. There was also the day when a “big, thuggish” repo man appeared at his door to repossess a car his stepfather had given him. “That, for a strange reason, scared the hell out of me,” says Goldsmith, who says that may have been the moment he decided that he couldn’t depend on his stepfather. After college, Goldsmith—who’d been legally adopted by O’Brien and taken his last name—went to court to change his name back to Goldsmith. It devastated his stepfather, and, as O’Brien’s legal troubles grew, “I basically tossed him under the bus.” Goldsmith winces now at the memory: “It was really an act of pretty extraordinary disloyalty.”

His rejection of his stepfather accelerated. During law school, Goldsmith took a job with a D.C. firm, Miller, Cassidy, Larroca & Lewin, where three of the name partners had been involved in Robert Kennedy’s efforts to get Hoffa. Goldsmith didn’t tell the firm of his own connection to Hoffa, and he now believes that he chose the firm because it included lawyers “who Chuckie knew and didn’t like, and they represented a conception of justice in the legal profession that was exactly the opposite of what [Chuckie] represented.”

Without the baggage of his stepfather—Goldsmith received security clearances after proving he’d cut off all ties to O’Brien—his career soared. In 2003, as assistant attorney general in charge of the Office of Legal Counsel in the Justice Department, Goldsmith concluded that Stellarwind, George W. Bush’s secret post-9/11 warrantless surveillance program, had serious legal problems, as he detailed in his 2007 New York Times bestseller, “The Terror Presidency.” Late one night, while researching the history of government surveillance, Goldsmith came upon a citation to O’Brien v. U.S., which had overturned his stepfather’s conviction for stealing a statue of St. Theresa from a sunken ship in the Detroit harbor because it was based on illegal wiretaps. “Basically, it was a validation of something he had told me a lot as a kid, which is that ‘these Justice Department sons of bitches, those elite, terrible people in the Justice Department, they break every law there is. They were bugging us and wiretapping us, and they were hounding us for violating the law, but they were violating the law,’” says Goldsmith.

The parallels with Goldsmith’s concerns about Stellarwind were striking. “I was sitting there working on a program that had many of those characteristics … reading about something similar that had happened to him that he had always told me about that I didn’t believe,” recalls Goldsmith. Over time, “I changed my views on a lot of things as a result.” Perhaps most consequentially, Goldsmith says, he came to “appreciate the dangers and evils of the surveillance state.” While he sees government surveillance as a vital tool for security, “I learned that there were these cycles of abuses related to surveillance and the government has a tendency to cut corners the way Chuckie said.”

The discovery of his stepfather’s Supreme Court victory prompted another major shift in Goldsmith. “I hadn’t thought about him in a long time; frankly, that was the beginning of a process that led us to reconcile.”

“We had barely spoken for two decades by the time of my service in the Justice Department. I left government in 2004 to become a professor at Harvard Law School, and soon afterward Chuckie and I patched up and once again grew very close. . . . ‘You don’t need to apologize, Son,’ he said. ‘I understand why you did what you did.’ And that was that. . . . For the rest of his life, he acted as if those twenty years didn’t happen.”

—In Hoffa’s Shadow

In 2012, Goldsmith began to research the Hoffa case and related issues. Through his research, Goldsmith says, he gained a much deeper appreciation of the American labor movement and the American worker that he had always had a kind of abstract academic attitude toward. “I had kind of favored employers over labor. I had a market theory about the way the world is supposed to work, and that didn’t survive untouched by this examination.”

His stepfather described carrying cash to a hotel room so president Nixon would commute Hoffa’s sentence.

His hundreds of conversations with O’Brien led to fascinating revelations about important historical events, including his stepfather’s jaw-dropping account of carrying a million dollars in cash to a hotel room so that Nixon would commute Hoffa’s prison sentence, a payoff about which rumors have swirled for decades. “There are a lot of things that I didn’t include in the book that he told me because I couldn’t verify it and I didn’t want to make the book sensationalistic—a lot of things,” says Goldsmith. “But that one I included because I was convinced by it.”

While always careful not to breach Omertà, his stepfather did share his eyewitness accounts of other major historical events; for one, he scoffed at longstanding rumors that Hoffa was involved in the assassination of John F. Kennedy. “I believe him on that, too,” says Goldsmith, although O’Brien says Hoffa did assist in providing airplanes and equipment for the Bay of Pigs invasion. One of the book’s many colorful anecdotes involves O’Brien delivering a human head from a cadaver to the editor of The Detroit News as a warning. After enormous effort, Goldsmith was able to corroborate the story, but he has no idea if it inspired the infamous horse-head-in-the-bed scene in “The Godfather.”

“The gods just decided to position him where so much of his life would be chewed up in the clash between an implacable government and an implacable Mafia.” —former FBI investigator Jim Dooley

—In Hoffa’s Shadow

But the key mystery, of course, was Hoffa’s fate. “What is truth when it comes to the Hoffa disappearance? This is one of the many frustrations I had in writing the book,” Goldsmith says. “There are literally 45 years of encrusted misinformation that has grown up in the public about what happened to Hoffa,” in large part due to strategic leaks to the media by law enforcement.

Ultimately, Goldsmith was unable to unmask what happened to Hoffa. However, after a meticulous scouring of all of the evidence, he is convinced his stepfather wasn’t involved in Hoffa’s death. “I don’t think he would have done it. That would have been the ultimate conflict for him, Omertà versus his love of Hoffa. I don’t think he had to face that.” Nor does he believe O’Brien actually knows who acted on the afternoon of July 30, 1975. “I think he knows more than he told me, but I don’t think he knows that.”

Key FBI investigators also became convinced that O’Brien wasn’t involved in Hoffa’s disappearance. One agent in particular offered to help clear O’Brien’s name; the FBI agreed that if he came in for one more interview, they would give him a letter exonerating him. Though in ill health and skeptical of the offer, O’Brien agreed, and Goldsmith accompanied him to the meeting. But for inexplicable reasons—perhaps embarrassment over the government’s having fingered the wrong man for so long—then-U.S. Attorney for Michigan Barbara McQuade refused to follow through.

“The world still thinks he did it, but the government came to believe he had nothing to do with it,” says Goldsmith. “I so wanted him to have that letter for all the pain he had gone through. I was absolutely furious, but there was no recourse.”

There is a paradox at the heart of this story that may help assuage Goldsmith’s regret for the way he treated his stepfather: Had he not rejected his stepfather for two decades, it’s unlikely Goldsmith’s legal career would have carried him to a top position in the Justice Department. And without those prestigious credentials, would the FBI have assisted him in his research? Would the U.S. attorney have agreed to meet with Goldsmith as he urged them to exonerate O’Brien?

“There is no doubt that these people knew who I was from the Bush administration, and there is no doubt that they talked to me and arranged this deal and we had these conversations and they trusted me in part because of that. … [T]hey might not have done that for just anyone,” Goldsmith agrees.

Still, it wasn’t enough. O’Brien, who never trusted the feds’ offer, was perhaps less disappointed than his stepson.

O’Brien, who recently turned 86, lives in Florida with Goldsmith’s mother, Brenda, and is a doting grandfather to Goldsmith’s children. “We talk every day, and he is a great guy and my children love him,” says Goldsmith. “He has just got this weird charm and integrity. It’s very hard to explain.” Goldsmith planned to publish the book after his stepfather’s death. But a new Martin Scorsese movie, “The Irishman,” was scheduled to be released in the fall of 2019, and, like so many films and books, it portrays O’Brien as complicit in Hoffa’s vanishing. O’Brien wanted his truth to be told.

“He knew that I had a lot of evidence that cleared him from the charge, so he wanted the book out,” says Goldsmith, who shared the manuscript with his stepfather last spring. “I said, ‘What do you think?’ And he had a very sad face, and he said to me: ‘I read every word. You wrote a great book. Congratulations.’” Goldsmith, always alert to his stepfather’s truth-shaping, wonders: “Did he actually read every word—is he OK with it? Did he not read it because he didn’t want to know? Did he read it and hate it, but he loves me so much he wants me to publish it? I don’t know. I still don’t know.”

“I wasn’t looking out for Chuckie [in the past and it] made me wonder how much I was looking out for him in writing this book.”

—In Hoffa’s Shadow

While Goldsmith says he’d worried about reactions to the book and how they might affect his elderly stepfather, O’Brien was delighted with reviews that believed the evidence cleared him of involvement in Hoffa’s disappearance. Still, there are “a lot of other ways it might be viewed and a lot of mean things that might be said about him and me,” Goldsmith says.

But he has no uncertainty about his stepfather’s feelings for him. “My favorite picture in the book is Chuckie wearing his Harvard T-shirt,” he says. Although Goldsmith has worked for institutions O’Brien doesn’t think much of (such as Harvard) or that he outright hates (the Department of Justice), nonetheless, “He is very proud of me, and it makes me very happy,” says Goldsmith.

“We ended up in a very, very amazingly great place as a result of this, but it was not … a single easy line. It was an extremely complicated experience.” As for the Hoffa disappearance, now that the book project is completed, Goldsmith says, “We haven’t talked about it since.”