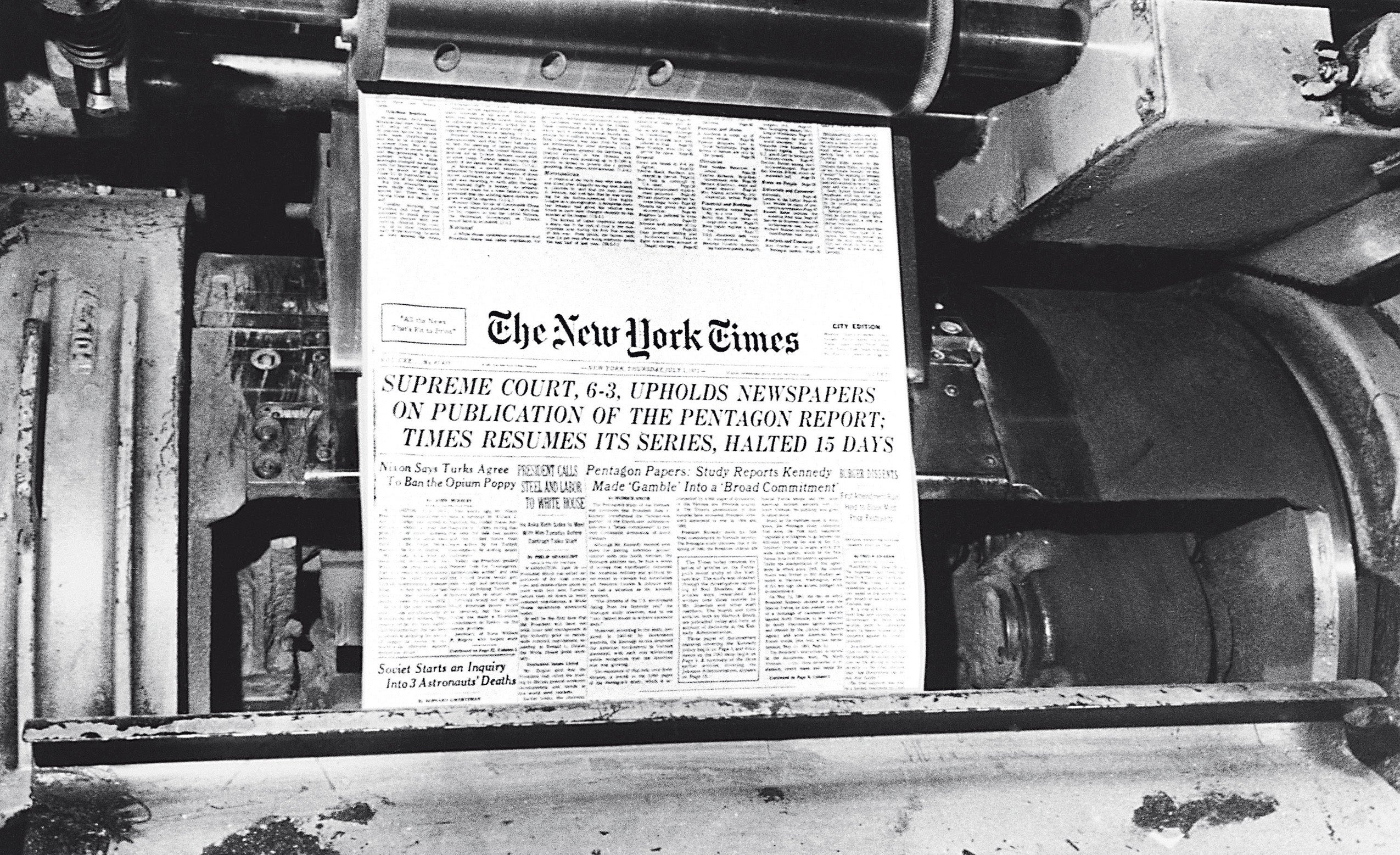

The First Amendment shields the press, Justice Hugo L. Black wrote 50 years ago in a concurring opinion in the Pentagon Papers case, so the press can “bare the secrets of government and inform the people.” In that historic ruling, the Supreme Court put an end to a temporary injunction against publication of the Defense Department’s secret history of the American involvement in the Vietnam War.

The ruling in the Pentagon Papers case legitimized the media’s status as what historian Stanley I. Kutler called “the people’s paladin against official wrongdoing.”

The Court allowed The New York Times, The Washington Post, and other newspapers to carry on publishing excerpts from the Papers’ 7,000 pages, revealing how the government used secrecy to deceive the American people about the nation’s disastrous role in the war. The advocates for the Times and for the government were eminent members of the Harvard Law School community: alumnus Alexander M. Bickel LL.B. ’49, a Yale Law School professor; and Solicitor General Erwin N. Griswold LL.B. ’28 S.J.D. ’29, who was HLS dean from 1946 to ’67 until he joined the Justice Department. The ruling legitimized the media’s status as what historian Stanley I. Kutler called “the people’s paladin against official wrongdoing.”

The ruling rests on the principle that free speech, embodied in a free press, is an essential element of American democracy. Except when publication would do grave and irreparable harm to the nation, the risk of damaging democracy by publishing information is preferable to the risk of undoing it by allowing the government to decide what citizens can know. When a government for itself supplants government for the people, the misrule of power displaces the rule of law: Autocracy takes over democracy.

The government based its case against the newspapers on the Espionage Act of 1917. That old law aimed mainly to curtail spying by punishing disclosure to foreign enemies of secrets about national security. In 1973, two years after the Pentagon Papers decision, the Columbia Law Review published an exhaustive analysis of the Espionage Act, explaining the law’s “fundamental problem”: It is “in many respects incomprehensible.” In a concurring opinion in the case, Justice Byron R. White had read meaning into the law, suggesting that it might be a crime for a newspaper to publish information classified as secret — and suggesting that the paper could be punished for doing so. The law review called White’s opinion “dicta amounting to admonition” — “a loaded gun pointed at newspapers and reporters who publish foreign policy and defense secrets.”

A concurring opinion in the case drawing on the Espionage Act of 1917 has been called “a loaded gun pointed at newspapers and reporters who publish foreign policy and defense secrets.”

That gun was also pointed at leakers. The Justice Department charged Daniel Ellsberg with espionage and theft for leaking the Pentagon Papers to the Times. At his trial in Los Angeles, Ellsberg was represented by Leonard Boudin, a renowned civil liberties lawyer who was a visiting lecturer at HLS, and Charles R. Nesson ’63, then a junior professor at HLS, now in his 55th year teaching at the school. Their client might have been convicted and sentenced to prison if another secret had not become public — the burglary of the office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist in search of embarrassing material at the behest of President Richard M. Nixon. Those “bizarre events,” as the judge called the incident, led to the end of Ellsberg’s case and helped propel the end of Nixon’s presidency. But it did not restrict the government’s authority to prosecute future whistleblowers.

In 1985, a federal trial court applied White’s logic from the Pentagon Papers case and convicted Samuel Loring Morison, a government analyst, for espionage and theft, for providing Jane’s Defence Weekly with photographs taken by a U.S. spy satellite of the Soviets’ first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier. Morison’s lawyer portrayed him as a whistleblower, who let the Western world know about the Soviet carrier. The lawyer contended that the benefit of publication outweighed the harm, since the Soviets already knew about the satellite. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit upheld the convictions, rejecting the argument that leaks to the press were exempt from the Espionage Act.

In January of 2001, before leaving office, President Bill Clinton pardoned Morison, after Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan told Clinton that the prosecution had been unfair, for “an activity which has become a routine aspect of government life: leaking information to the press in order to bring pressure to bear on a policy question.” (In the Pentagon Papers case, Max Frankel, the Times’ Washington bureau chief, made a similar point: “Without the use of ‘secrets’ that I shall attempt to explain in this affidavit, there could be no adequate diplomatic, military and political reporting of the kind our people take for granted, either abroad or in Washington and there could be no mature system of communication between the Government and the people.”)

Still, the precedent of Morison’s conviction for disclosing classified information to the press remains valid law. In the Obama and Trump administrations, the government indicted a dozen people for leaking secrets to the press, with the former normalizing the practice and the latter building on the norm. The 2013 case against U.S. Army Private Chelsea Manning for leaking a huge number of secret documents to WikiLeaks was among the most prominent examples. She was convicted and sentenced to 35 years in prison and dishonorably discharged (though President Obama commuted most of her sentence).

The Constitution, including the First Amendment, does not protect leakers against prosecution and punishment for unauthorized disclosures. But does it protect members of the media when they receive in a lawful manner classified information unlawfully obtained?

In 2013, The Washington Post reported, the Obama Justice Department decided not to indict Julian Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks, for conspiring with Manning because Assange did not leak the documents. As former Justice Department spokesman Matthew Miller told the Post, there would have been “no way to prosecute him for publishing information without the same theory being applied to journalists.” That created a “New York Times problem”: If the government indicted Assange, it would have to indict the Times and other news organizations and journalists that published the classified information. That impediment, however, didn’t stop the Trump administration, which indicted Assange in 2019 (the first time the government has prosecuted a publisher based on the Espionage Act), saying that Assange “is no journalist” and that the administration took “seriously the role of journalists in our democracy.”

The Assange case underscores how different the world is today from 50 years ago. The terrorist attack on the United States on Sept. 11, 2001, led to the expansion of the power of the executive branch and to the magnification of national security as an American concern, leading to a large increase in the number of people with security clearances and access to classified information. It also led to exponential growth in the amount of classified information — a realm “so large, so unwieldy and so secretive,” as The Washington Post explained, “no one knows how much money it costs, how many people it employs, how many programs exist within it or exactly how many agencies do the same work.” New technology has led much of the information to be digitized, making it much easier for secret information to be copied, leaked, and communicated over the internet — and for the government to track down leakers.

This April, First Amendment scholars Lee C. Bollinger and Geoffrey R. Stone published “National Security, Leaks and Freedom of the Press,” subtitled “The Pentagon Papers Fifty Years On.” They write: “[T]he risks of both too much secrecy and too much disclosure are arguably very different from what they were in 1971 and the ensuing decades.” They conclude that while national-security experts worry about too much disclosure and civil liberties experts warn about too much secrecy, their “profoundly important collective judgment” is that the current system of law and practices “has worked reasonably well.”

In the Bollinger-Stone volume of essays, Harvard Law Professor Jack Goldsmith contends that the small number of prosecutions of leakers compared with the large quantity and breadth of leaks since 9/11 reflects “an unprecedented growth in press freedoms in the national security context” — and that the Trump indictment of Assange confirms the norm of “greater protection of journalists” because the administration stressed that the indictment was no threat to the press.

Jameel Jaffer ’99, executive director of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, argues that the U.S. has “paid a staggering price for excessive secrecy” since 9/11; that leaks have exposed some of that price in the form of abuses at Abu Ghraib, the National Security Agency’s massive collection of Americans’ telephone records, and other violations of law, and have led to “significant adjustments to policies relating to interrogation, detention, surveillance, and extrajudicial killing”; and that, in addition to clarifying that American law distinguishes between leaking to the press and to foreign spies, the law should provide much stronger protection for leakers who are whistleblowers, because developments in the past two decades have made Americans “more reliant on whistleblowers even as they have made whistleblowing more difficult and more hazardous.”

Goldsmith and Jaffer disagree fundamentally about how much secrecy American democracy needs and whether the balance now unduly favors secrecy or free speech. They agree as deeply about the need for the press’s bright light to bare secrets of government. To Jaffer, that’s “crucial to our democracy.” To Goldsmith, it’s “vital.”

Lincoln Caplan ’76 is a visiting lecturer and a senior research scholar at Yale Law School and the author of six books, including “American Justice 2016: The Political Supreme Court.” He last wrote for the Harvard Law Bulletin in the Winter 2020 issue.