American city life changed drastically when the coronavirus arrived in the late winter of 2020. Almost overnight, offices emptied, bars and restaurants shut down, and droves of people whose jobs or finances allowed it packed up and moved away. Now, three years later, cities are ready for a comeback, say several Harvard Law School alumni who have served as mayors of cities ranging in size from 100,000 to nearly 2.3 million people. And if local leaders do things right, they say, cities can come back stronger than ever before.

Urban America faced hard times long before the pandemic. Growing wealth inequality, suburban flight, and outdated infrastructure had already left many municipalities with strained finances and uncertain futures. But the pandemic, in addition to exacerbating the issues cities were already dealing with, posed a brand-new, nearly existential challenge of its own. In an October 2022 lecture marking his appointment as Steven and Maureen Klinsky Visiting Professor of Practice, Julián Castro ’00 described the dismay he felt when headlines of stories published in the early days of the pandemic repeated the conventional wisdom that cities were dying.

City leaders now confront a backlog of challenges, from the affordable housing crisis to climate change to public safety.

What once made American downtowns magical — bustling bars and restaurants, crowded concert venues, sports arenas full of cheering fans — now turned them into nightmares. Cities were left facing their “toughest years,” said Castro, a former mayor of San Antonio and secretary of Housing and Urban Development under President Barack Obama ’91.

As the pandemic disrupted and displaced lives, cities struggled with evictions and homelessness, rising crime rates, and shuttering businesses. As jobs and people left, tax revenues dried up, and local governments struggled to provide basic services. COVID-19 threatened the very point of cities, says John Cranley ’99, who served two terms as mayor of Cincinnati from 2013 to 2022. “The archetypal virtue that urbanists believe in is bringing people together in the beloved city,” where people of different backgrounds can work and live alongside each other, Cranley said. “And COVID sent the message for years for people to spread out and stay away from each other.”

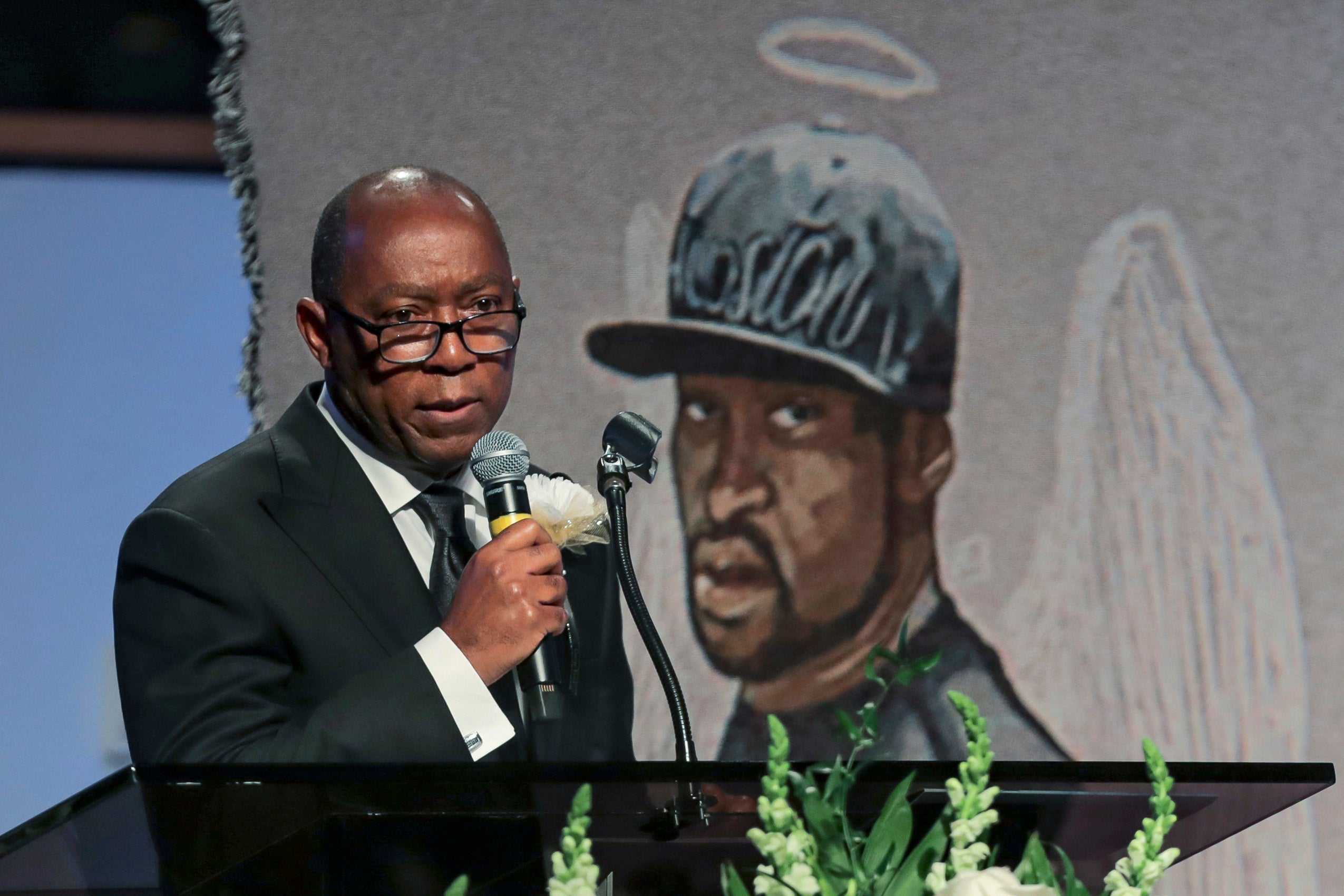

But as COVID’s immediacy wanes and the world begins to adapt to the endemic, local leaders must confront a backlog of challenges. The mayors of cities both big and small agree that while the problems faced by each differ in scope — as do resources available to solve them — cities nationwide are dealing with largely the same sets of issues. “We all do the same thing,” said Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner ’80, who for the past seven years has led the fourth-largest city in the nation. “Whether it’s COVID, monkeypox, flooding issues, homelessness, or public safety, we all have to address those issues in real time.”

Housing and affordability

Top of mind nationwide is the growing housing affordability crisis. Prices for single-family homes in the United States have skyrocketed in recent years, with pent-up demand during COVID pushing prices far past what many residents can afford. Home prices have increased by double-digit percentages, climbing as high as 37.1% year over year in Detroit. Rental markets have often followed suit. Though housing markets are expected to cool as mortgage interest rates climb, residents nationwide still struggle with affordability.

Despite record-breaking federal investment in state and local infrastructure, neither Rome nor Richmond can be built in a day. So, many cities, inspired in part by creative uses of public lands that arose during the pandemic, are trying to reuse and reimagine existing, but underutilized, spaces. As one example, Castro cites California’s Project Roomkey, an initiative that helped secure temporary housing for homeless people in unused hotel and motel rooms. The program later transformed into Homekey, involving the purchase and renovation of entire hotels, which can then provide permanent housing and support services for vulnerable communities.

“We will never be successful as long as the challenge is how to most fairly or least painfully allocate a shrinking pie or even one that is of a fixed size. We have to grow it.”

—Michelle Wu

In Boston, where little land remains open for development, Mayor Michelle Wu ’12 is focused on finding opportunities to build climate-resilient, accessible, and affordable housing on underutilized city-owned land. “We will never be successful as long as the challenge is how to most fairly or least painfully allocate a shrinking pie or even one that is of a fixed size,” Wu said in an October interview in The New York Times Magazine. “We have to grow it.”

In nearby Lynn, Massachusetts, the city has created an affordable housing trust fund with input from renters, developers, and other stakeholders, says Mayor Jared Nicholson ’14. The purpose is to raise and allocate funds from a variety of sources aimed at building more affordable housing. Lynn is also focused on ensuring that there are enough homes for residents of all income levels, and the city has attracted nearly $500 million in private development to build additional residences, says Nicholson.

Though housing is a nationwide problem, Nicholson says, local solutions are still needed. “It is important to not let the fact that an issue is bigger than just the city of Lynn be an excuse for not addressing it,” he said. “We can want to see and advocate for everybody to step up and help solve this problem and continue to do more for ourselves because it’s our residents who are struggling with the issue.”

Clockwise from top left: Boston Mayor Michelle Wu ’12; former Mayor of Cincinnati John Cranley ’99; Jared Nicholson ’14, mayor of Lynn, Massachusetts; Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner ’80; Julián Castro ’00, former mayor of San Antonio and secretary of Housing and Urban Development

Policing and public safety

The murder of George Floyd, and the protests against police brutality and racism that followed, sparked a national debate about the role of police and inspired calls for shifting funding from police departments to social services. In his Klinsky lecture, Castro cited Denver as having implemented one particularly successful example of this approach to criminal justice reform. In June 2020, Denver launched the Support Team Assisted Response program, an initiative that has sent mental health workers and EMTs to respond to crisis calls that previously drew a law enforcement presence. The program, which has responded to approximately 6,000 calls so far, is expanding due to its success, with one study finding that it resulted in significantly fewer criminal offenses and large cost savings. Inspired by such examples, Lynn is currently working on creating a similar unarmed crisis response team, according to Nicholson.

Rising crime rates, however, have posed a challenge, and, tasked with maintaining public safety, cities have continued to lean on traditional law enforcement responses. In Houston, a $53 million investment from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 has funded a larger police presence, a gun buyback program, additional domestic violence prevention outreach efforts, and an increased focus on youth services designed to draw adolescents away from juvenile crime and gang involvement. According to Turner, these initiatives appear to be succeeding in his city, with homicides and violent crime rates beginning again to trend downward.

Going forward, cities must learn to navigate these challenges with care and creativity, says Cranley. Work begun in his own city two decades ago may serve as a case study. In April 2001, a white police officer in Cincinnati shot and killed 19-year-old Timothy Thomas, an unarmed Black man, while attempting to arrest him for nonviolent misdemeanors. The killing set off four days of rioting and civil unrest and marked the largest urban disturbance in the U.S. since the 1992 Los Angeles riots that erupted after a jury acquitted police officers who had beaten Rodney King. In response, Cincinnati launched police department reforms known as the Collaborative Agreement, which brought police and local residents together to work collaboratively on questions concerning law enforcement within the Cincinnati community. “It completely changed the culture and ethos of our police department, and while the police resisted it 20 years ago, they now brag about it and are converts,” Cranley said.

He believes that the efforts have made a difference. After the murder of George Floyd, Cincinnati residents engaged in weeks of peaceful protests, and the city experienced relatively little of the unrest that plagued other urban areas. “All of our communications and relationships that we’ve built in 20 years paid off,” said Cranley, who shared the lessons learned with other mayors. “We’re not perfect, but we’ve made real progress, and I think it’s a role model for other cities.”

Public health lessons for the future

Though COVID’s impacts reached every sector of life, at heart, the pandemic was a public health crisis for which the country was woefully unprepared, say alumni mayors. “The pandemic really showed that the country’s public health infrastructure was underdeveloped,” said Nicholson. In response, he said, Lynn grew its public health team. The Lynn Public Schools also hired dozens of social workers and clinicians to address the related mental health crisis that became starkly apparent as the pandemic isolated individuals and families and disrupted every facet of normal life.

“There’s an opportunity [to take lessons] learned during the pandemic … to deliver health care more effectively.”

—Julián Castro

Cranley notes that throughout COVID, personal protective equipment and vaccines were distributed locally rather than federally, leaving cities to address a problem the country had not seen in more than 100 years. “Many people, myself included, were kind of uneducated on the role of public health because it had been so long since there was a major pandemic,” Cranley said. “There was no manual, and though we ultimately got money from the federal government, which we needed, we had to build the infrastructure ourselves.”

Castro is optimistic that, now that the infrastructure is in place, cities can use their more robust public health awareness, experience, and community engagement to improve health outcomes even in the absence of a crisis. He notes that, before the pandemic, people in poor communities often used emergency rooms in lieu of primary care physicians. That could change, Castro hopes, as an indirect result of successful, widespread vaccination campaigns, which brought preventive care to underserved communities. “There’s an opportunity in the realm of public health to take some of the lessons that were learned during the pandemic about being transparent and communicating with residents and … harness that in the future to deliver health care more effectively and to more people in a lifelong process,” he said in an interview.

Combating climate change

As many learned acutely during the pandemic, cities, despite their size, often face challenges that are national or global in scope. Perhaps the starkest example of this dynamic is climate change, a global problem that forces local communities to grapple with how to keep their residents safe when rising temperatures contribute to extreme weather patterns and natural disasters.

Houston has had to deal with seven federally declared disasters in the last seven years. Its mayor has tried to turn these catastrophic events into an opportunity for big changes.

Four months into Turner’s first term as mayor, Houston was hit with a devastating flood during which almost 24 inches of rain fell in 24 hours, flooding tens of thousands of homes, killing multiple people, and causing millions of dollars in damage. The following year, Hurricane Harvey brought approximately 52 inches of rain to the city. Houston has had to deal with seven federally declared disasters in the last seven years.

Turner has tried to turn these catastrophic events into an opportunity for big changes. Hurricane Harvey, which brought devastation straight to the country’s energy capital, helped kickstart a flurry of climate initiatives, he says. The famously sprawling city began building higher while adding environmentally sustainable and flood-resilient infrastructure. Houston partnered with energy and utility companies to convert all municipal operations to renewable energy sources. “The reality is, when you’re dealing with challenges or events that you either can’t foresee or you can’t prevent, cities and mayors simply have to manage the situation,” Turner said. “And if you weren’t someone who was just caught up on the environment, you had to look at the economic consequences of a failure to act.”

And while no one municipality can single-handedly reverse climate change, by virtue of their size, cities can take quick actions that still have significant effects, says Cranley. When the United States pulled out of the Paris Agreement in 2017, for instance, Cranley, like many mayors, vowed to make carbon emissions reductions anyway. By October 2021, Cincinnati had built the nation’s largest municipally owned solar farm. “Cities are far more direct, nimble, and on the ground,” Cranley said. “I could just do my thing on my own.”

The future of cities

Cities, like just about everything else, are different now. Cranley’s biggest fear is that, with the rise of remote work, they may never look again quite like they did before COVID. In 2020, Cincinnati’s population had just grown for the first time in 70 years, reversing a trend of decline that is widespread in the Midwest. But if people can live elsewhere without losing their livelihoods, Cranley fears there will be a return to population loss and urban decline. “For cities like Cincinnati, a permanent move to remote work by some significant portion of the workforce is an economic and existential threat to the viability of cities, which are premised on density and the proximity of where people live, work, and play,” he said.

The future of cities depends not just on attracting resources, but on using them to build more equitable communities.

But this is not the first time cities have had to adapt to a changing world. Nicholson points out that Lynn was once a proud industrial center (known as the shoe capital of the world), but the factories that once employed tens of thousands of residents have closed or scaled down and are unlikely to return to the same scale. So, Lynn has had to learn to pivot. Capitalizing on its proximity to Boston, Lynn has worked with trade groups to attract life sciences employers while simultaneously developing workforce programs to build necessary skill sets for the industry.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis LL.B. 1877 once described states as places that could “serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.” These days, Castro is optimistic that cities can play much the same role. One experiment he hopes they will undertake is to begin looking beyond their own boundaries and cooperate with suburbs to address issues as regions, rather than as individual localities. Regional economies are simply stronger than municipal economies, and regional solutions to problems are more likely to be successful than localized ones, Castro remarked during his Klinsky lecture. “The smartest cities are those that can find a way to begin a dialogue and ultimately to act in a regional way on economic development, on affordable housing, and on linking that affordable housing to transit opportunities and job opportunities,” he said.

“The limits of the city’s ability to raise revenue certainly is not a limitation on our imagination about how we can serve our residents.”

—Jared Nicholson

To a large extent, the ability of cities to successfully navigate these challenges will depend on more than just their willingness to collaborate with neighbors. Many cities’ fates rest on decisions made far beyond City Hall. In the past few years, urban centers have benefited from unprecedented sums of federal funding, including most recently from the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, which directed hundreds of billions of dollars toward energy security and climate change, much of which will be allocated via grants for local projects. But these funds will eventually and inevitably wane, particularly if feared significant economic decline comes to pass. “All water flows downhill, so whatever happens at the federal level, and whatever happens at the state level, cities will have to deal with whatever decisions are made above them,” Turner said.

But whether revenues rise or fall, Nicholson is optimistic that resourcefulness, creativity, and grit will help places like Lynn pull through whatever economic challenges arise. “The limits of the city’s ability to raise revenue certainly is not a limitation on our imagination about how we can serve our residents,” he said.

For Castro, the future of cities depends not solely on the resources that they can attract from state and federal coffers, but also on how they can use them to build more equitable communities. He hopes local governments will treat COVID as more than a temporary crisis, and instead as an opportunity to reimagine approaches to economic development, education, transit, and health care, all with the aim of creating spaces where people of all means can thrive. “I want the best of cities to continue to shine through, but for them to be places for everyone,” Castro said.