When Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson ’04 was fresh out of college, she moved from Massachusetts to Alabama to work for the Southern Poverty Law Center, where she investigated hate groups and hate crimes. While there, she visited the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, and was inspired by the individuals who had “faced down significant violence, and some lost their lives, simply so everyone could vote.” Two decades later, she would return to the bridge as the last stop on a 2019 voting rights tour through Alabama that Benson organized for 20 bipartisan secretaries of state.

Benson enrolled at Harvard Law School with the singular goal of becoming a voting rights attorney. As a research assistant to former HLS Professor Christopher Edley Jr. ’78, she explored the intersection of academia and advocacy by working to pass the 2002 Help America Vote Act in the wake of the controversial 2000 presidential election. After graduating and completing a clerkship, Benson taught election law at Michigan’s Wayne State University Law School, where in 2014 she was appointed dean and became the youngest woman ever to lead an American law school.

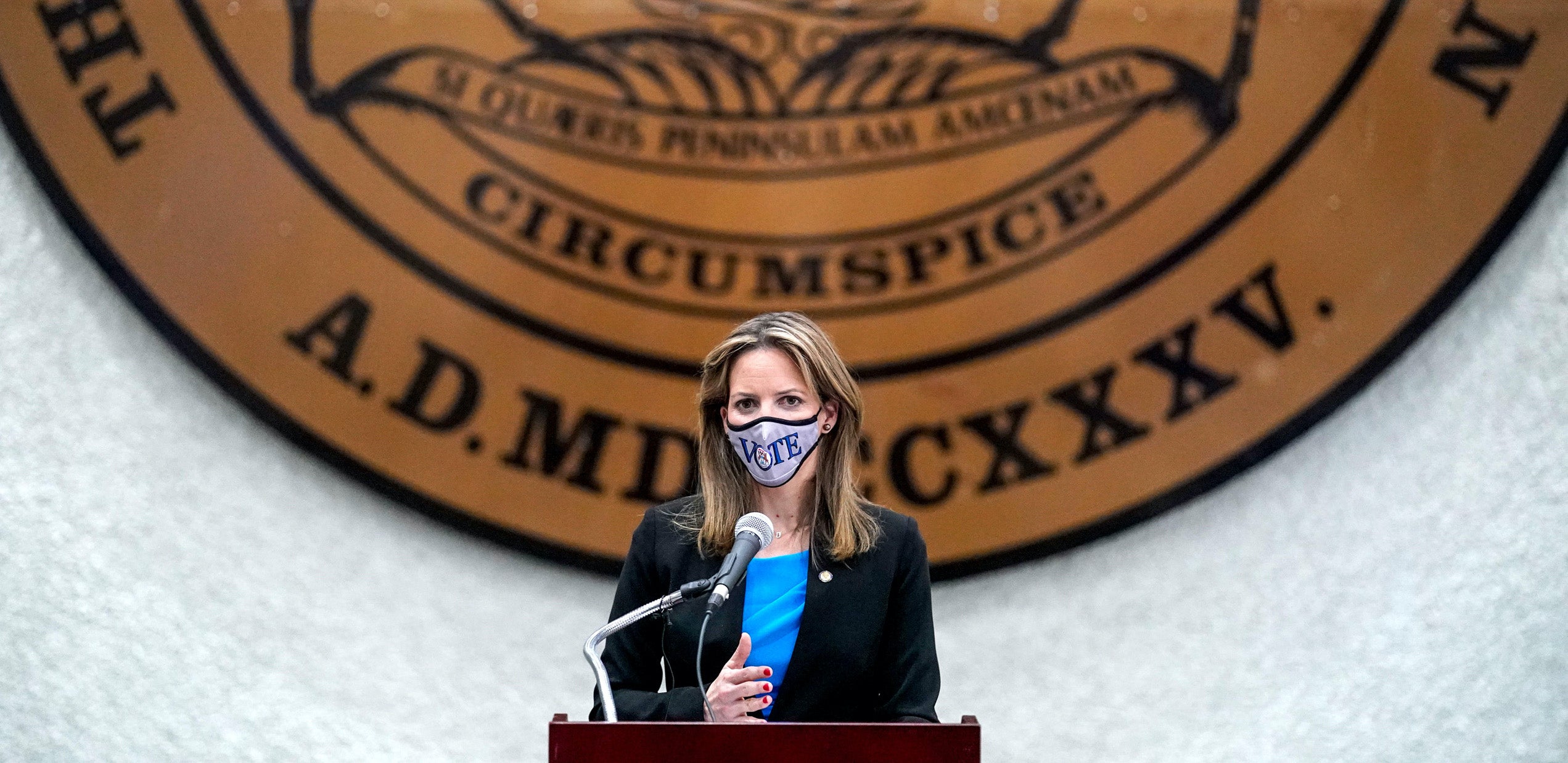

After an unsuccessful run for secretary of state in 2010, Benson ran again in 2018 and became the first Democrat in the seat since 1995. Now, as the head of elections in a closely watched battleground state, she is making the kinds of decisions that have brought new focus to the important work of election administrators. In the run-up to 2020, Benson worked to implement and promote unprecedented levels of mail-in voting and to ensure that in-person voting remained safe and accessible. She collaborated with both Republican and Democratic secretaries of state nationwide to develop plans and protocols for conducting an election likely to attract record participation even as a raging pandemic created staggering logistical challenges.

From an administrative perspective, the election turned out to be a “huge success,” said Benson. A record number of voters participated; few ballots arrived late or needed to be rejected due to voter error; in-person voting ran smoothly on Election Day; and votes were tabulated ahead of schedule. But as results poured in, so did massive public scrutiny and lawsuits as former President Donald J. Trump and his allies sought first to halt the counting of votes in the state, and later to overturn the results.

“We were prepared for everything with regard to this last election cycle, except for the levels to which people would stoop to try to stop democracy and deny the voice of the people.”

Benson was surprised by the vehemence of the distrust she saw, which grew in pitch before culminating in the unprecedented Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol. Protestors had gathered outside her home to chant “Stop the steal” as she and her 4-year-old son put up Christmas decorations. “We were prepared for everything with regard to this last election cycle, except for the levels to which people would stoop to really try to stop democracy and deny the voice of the people,” she said.

The 2020 election may be behind us, but Benson warns that in its wake, after a record-breaking turnout, the nation must reckon with concerted efforts in nearly every state legislature to reduce voting access. She sees a need for strong federal oversight to protect against the rollback of voting rights, coupled with state and local efforts to create greater transparency, and to reduce the role of partisanship, in election administration. “Voters want election administrators to be the referees of democracy, to guard every vote, and not put their thumb on the scale for one side or the other,” Benson said.

Until the coronavirus pandemic hit, Benson ran two marathons a year, including the 2016 Boston Marathon, which she completed just before giving birth to her first child. She thought the iconic race was out of reach, until she read about a woman who, like Benson, was eight months pregnant when she ran it. Suddenly, the same drive that would later guide her through an election cycle burdened by the dual crises of a global pandemic and a deeply divided electorate convinced her to give it a try. “I realized that I wanted to do it so that other women could believe they could as well,” Benson said. “You have power yourself over defining your limits and pushing your limits and defining the extent of what you’re going to do in this world.”