Racial reconciliation in America has been an elusive dream. To Bryan Stevenson ’85, the problem is that we haven’t been willing to tell the truth about our nightmares.

“Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror,” a report released in February by Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative, tells its piece of that truth in unflinching detail. Its pages lay bare a scheme of organized racial terrorism that murdered at least 3,959 people across the American South—retribution for “transgressions” like one man’s failing to call a police officer “Mister,” or a World War I veteran’s refusal to take off his Army uniform.

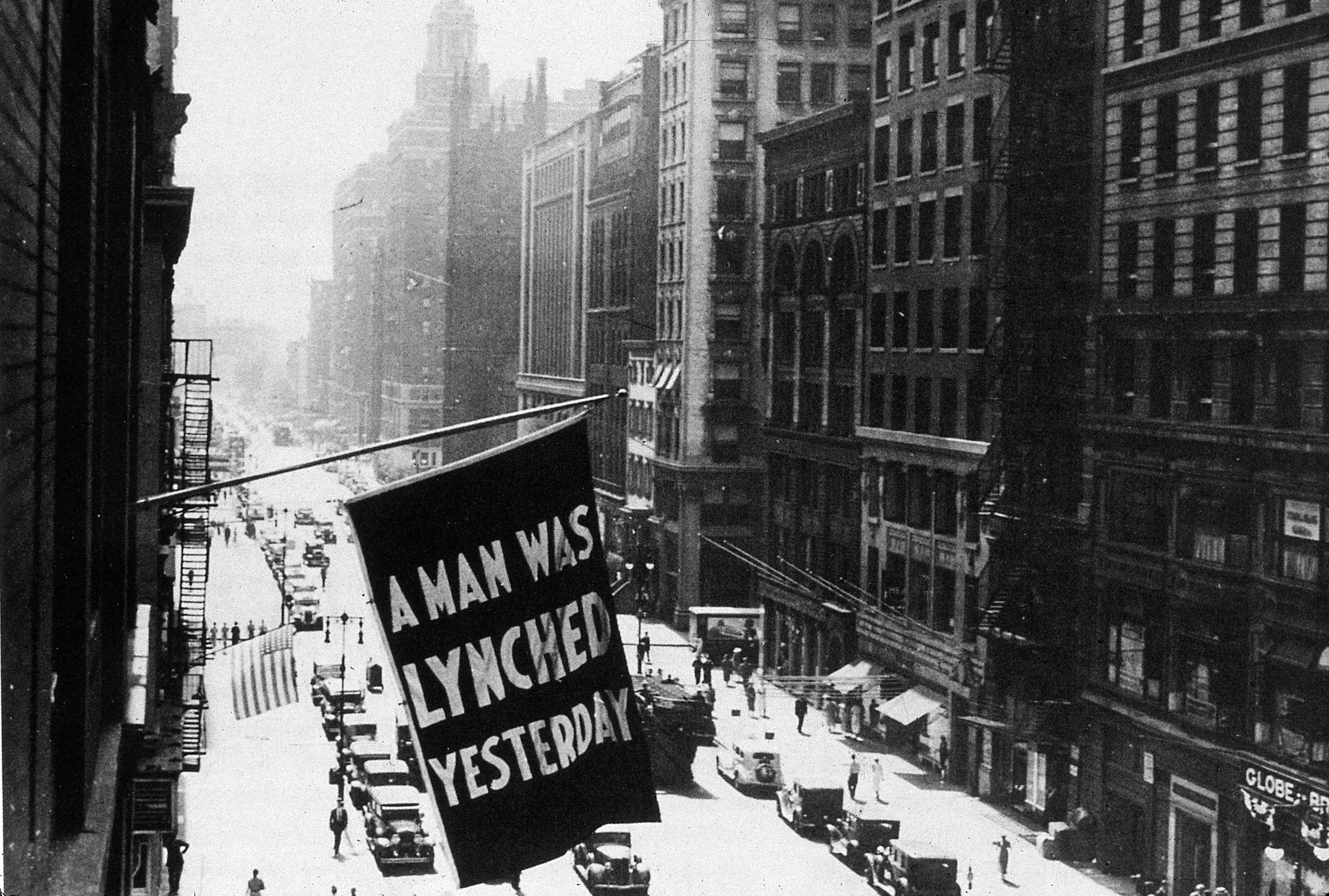

Images and anecdotes underscore a particularly public system of terror. A July 1919 Mississippi newspaper blares out in bold type, above the fold:

JOHN HARTFIELD WILL BE LYNCHED BY ELLISVILLE MOB AT 5 O’CLOCK THIS AFTERNOON

“Thousands of People Are Flocking Into Ellisville to Attend the Event,” reads the subhead.

A multigenerational crowd looks on, “enjoying deviled eggs, lemonade, and whiskey in a picnic-like atmosphere,” while two victims are tied to a tree, dismembered, and eventually burned to death. Another mob gouges out a man’s eyes with a scalding fire iron before shoving the poker down his throat, castrating him and slowly burning him alive.

Our criminal justice system, the report argues, remains contaminated by this history. Lynchings declined only as the court-ordered death penalty expanded, it notes, while African-Americans living today in communities where lynching was common remain “overrepresented in prisons and jails, and underrepresented in decisionmaking roles in the criminal justice system.”

There is no comfort in looking at this history—and little hope save the courage of those who survived it. But there may be no justice, Stevenson’s team maintains, until we stop looking away.