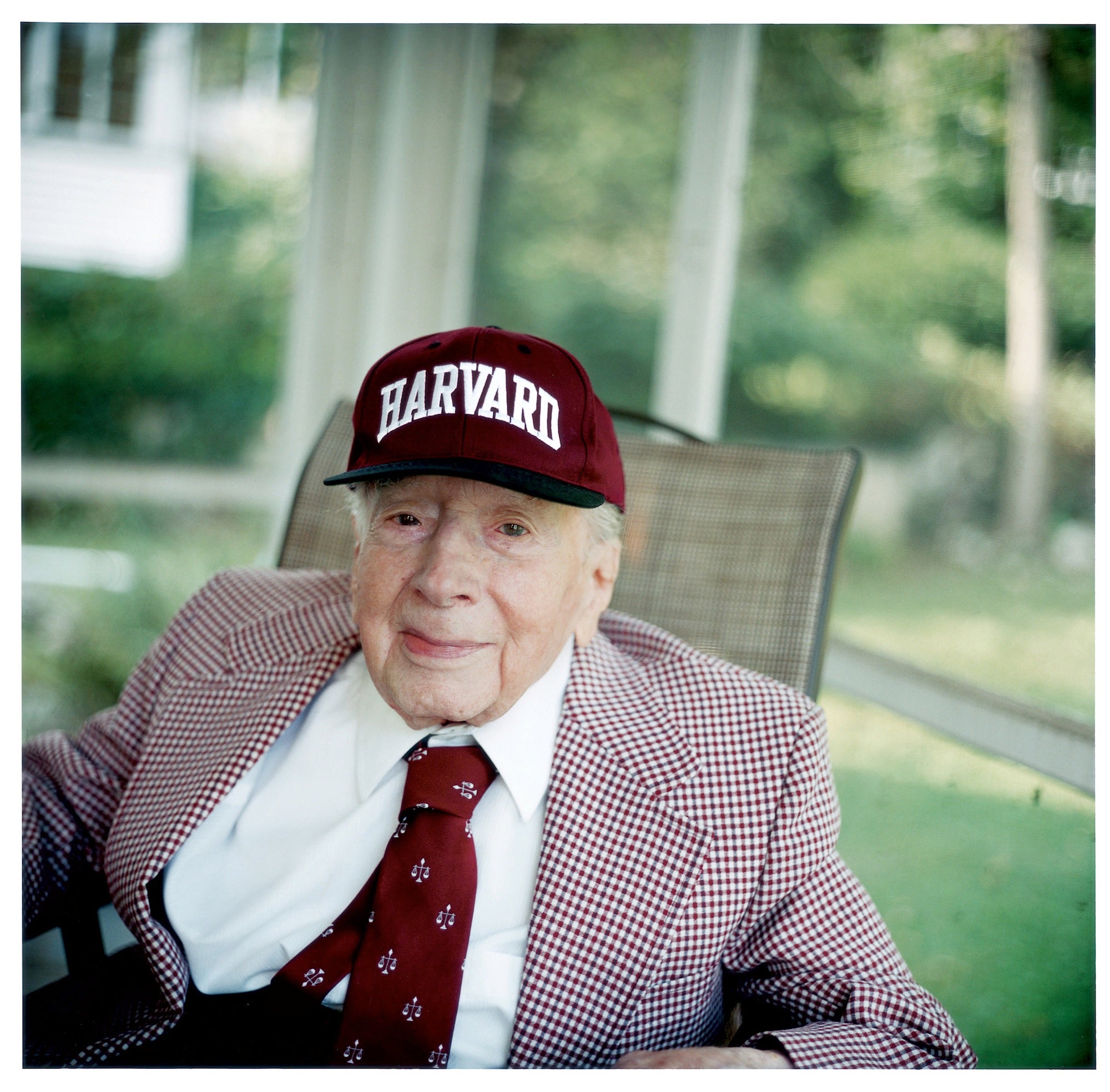

Walter Seward ’24 (’27), Harvard’s Oldest Living Graduate

Some honors take longer to attain than others. More than 75 years after graduating from law school, 108-year-old Walter Seward ’24 (’27) has earned distinction as Harvard’s oldest living graduate.

Born in Toledo, Ohio, on Oct. 13, 1896, Seward arrived at the law school when Roscoe Pound was dean and Edward “Bull” Warren 1900 and Felix Frankfurter 1906 were professors. Back then, LSATs didn’t exist, but Seward’s 1917 diploma from Rutgers easily got him in. Getting out with a degree was another matter. According to David Warrington, librarian for special collections at HLS, during Seward’s time about a third of every class dropped out. “Unless you passed the final exam,” said Seward, “you were out.”

A title attorney for many years, Seward married for the first time at 61. “I had established the idea that I would first have to get myself well settled before I could consider any marital propositions,” he said.

He met his wife, Florence Elizabeth “Betty” Gardner, a teacher 22 years his junior, in church. Their son, Jonathan, was born in 1960, and a daughter, Marymae Seward Henley, two years later, when Seward reached the age of mandatory retirement.

Seward delayed marriage and fatherhood, and he also appears to have postponed aging. He doesn’t wear dentures or need a hearing aid and uses eyeglasses only for reading. He lives in his own home in West Orange, N.J., and attends church every Sunday.

If there is a secret to his health and longevity, his daughter thinks it is exercise. He was a lifelong hiker and routinely did flexibility exercises. “Still to this day, he can lift his knee up and touch his chin,” said Henley.

Seward is happy for his longevity, but he’s not surprised by it. He doesn’t smoke or drink alcohol. He enjoys sweets, avoids caffeine and for many years regularly imbibed a mixture of honey and vinegar to ward off illness. A dose of tenaciousness has also helped. Nine years ago, he fell and broke his hip during a chapel service, but he refused to leave until the service was over.

In 1917, Seward was involved in an automobile accident that killed his father but may have saved his life. He was ineligible to serve in World War I because the leg he broke in the accident healed three inches shorter than the other. After his father’s death, he remained in New Jersey to complete the work his father began, preparing a map of Landis Township. Undecided whether to attend Harvard or Yale, he took the train to New Haven. When he got off at Yale, he had a look around. “I didn’t like it at all,” said Seward. “It was terrible.” He got back on the train and enrolled at Harvard.

Seward found his law school years to be a challenge. Classes were a tremendous amount of work, and with waiting tables to cover room and board, there wasn’t much time for anything else. But soon after Seward secured his LL.B., things got tougher. He had moved to Newark and was employed at Fidelity Union Title & Mortgage Guarantee Co. when the stock market crashed in 1929. “I had that job until things got so terribly bad, they had to fire everybody,” said Seward. “I had to pick up jobs now and then as best I could.” In the midst of the Depression, when one in four was unemployed, he found work at a classmate’s firm in New York City. In 1937, he returned to New Jersey, where he practiced law into his 90s.

“His life was always about working,” said Henley. “Retirement wasn’t really a thought.”

Seward, who attended HLS at a time when he says the law was a man’s profession, returned this past August and met with the school’s first female dean, Elena Kagan ’86. At a luncheon in his honor, the dean presented the once struggling student with a citation declaring Aug. 23, 2004, Walter Seward Day at Harvard Law School.

“It wasn’t easy getting through Harvard Law School the way I did it,” said Seward. “I managed it. I finally made it.”