Harvard Law School’s new program, and its faculty director, aim to change the way we think about environmental law

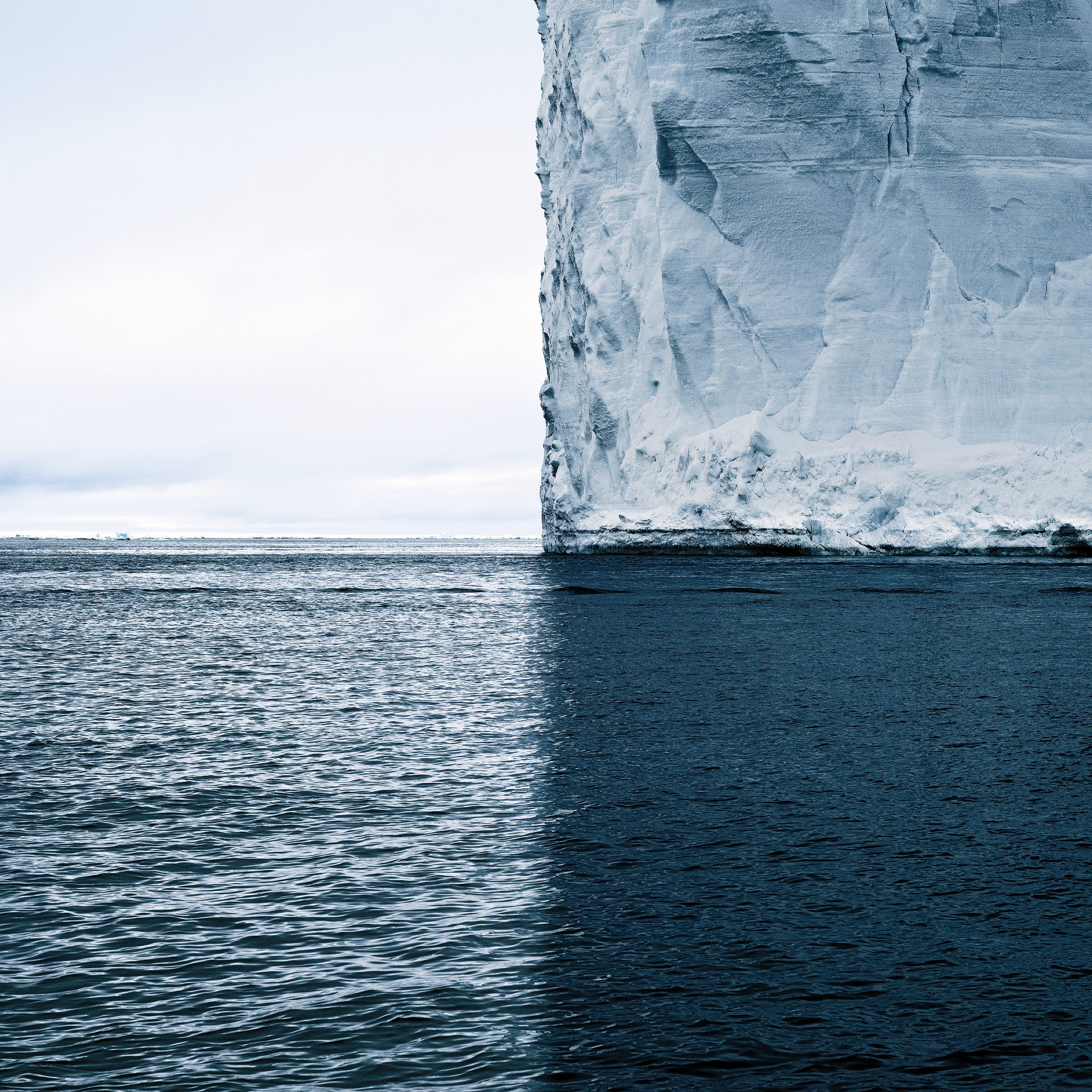

Rising sea levels, melting ice caps, increasing temperatures, struggling ecosystems, frequent and destructive storms—these are the early warning signs of global climate change. No one can predict all their implications, but experts say what is foreseeable could be devastating: diminishing fresh water supplies, destruction of coastal societies, droughts and floods, mass extinctions and rampant disease.

To avoid the worst impacts, scientists say, the global community must drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions—a task that will require a massive effort by individuals, businesses, NGOs and governments to develop and use regulatory, market and technological innovations.

How can lawyers help?

A Broad and Growing Curriculum

Since that first conference, the program has come a long way. It boasts a broad and growing curriculum; a new law and policy clinic; a mentoring program for emerging environmental law scholars; and discussion forums for national and international policy-makers, advocates, scholars, practitioners and investors.

“The timing is fortuitous,” says Antonio Rossmann ’71, an environmental law teacher at Boalt Hall and attorney with Rossmann & Moore in San Francisco. “Harvard will redefine environmental law education and set the national standard.”

That’s precisely what HLS Dean Elena Kagan ’86 had in mind when she made environmental law a priority upon becoming dean. “I wanted us to focus on these critical issues in really creative ways,” says Kagan. “Environmental problems will require solutions across borders and disciplines, both regulatory and market-based, and Jody Freeman, a superb scholar and teacher and a natural institution builder, is the perfect person to lead our efforts.”

Freeman brings a vision that’s intended to differentiate Harvard’s program from others, and to bring fresh ideas and solutions to the field. An instinctive convener and collaborator, she canvassed other leading law professors—including Georgetown’s Richard Lazarus ’79, Duke’s James Salzman ’89 and Robert Verchick ’89 of Loyola—and numerous prominent practitioners and policy-makers. The result: a program that is changing the way lawyers think about environmental law.

“A different role for lawyers”

Because environmental issues cut across every area of human endeavor, Freeman says, the program must train not only students who are planning environmental careers but also those who will practice in other areas of law. Litigation—the cornerstone of environmental law practice in the 1970s and 1980s—will always have its place, she says, but it’s now just one of many tools for addressing environmental issues. “Law students might wind up in business; they might wind up practicing law; they might wind up in politics. But they need to be exposed to a range of environmental issues, even if they don’t view themselves as ‘green’ or expect to work as environmental lawyers, because no matter what they do in the public or private sector, they’ll have an opportunity to impact the environment.”

When environmental law emerged as a discipline in the late 1960s, the priorities were all about cleaning up the air, water and land. The tools were legislation, regulation, enforcement and litigation. Today, climate change represents a new frontier, Freeman says, where we must rethink the world’s energy systems, invest in technology and engage with the developing world. Increasingly, environmental questions will be answered by what Freeman calls a “transactional market model”—at least as often as by the old litigation model.

“We are in an era when people are using markets as an approach to regulation, alongside and sometimes instead of command-and-control regulation, where government sets standards and requires firms to meet them,” Freeman says. “We’ve been building up to this point for a long time, but we’re now full-fledged in an era when regulators are going to be using instruments like markets more often, meaning the enterprise of system design on the front end, and enforcement on the back end, are both different. It calls for a different role for lawyers.”

To prepare students for that role, the law school now offers an expanding number of environmental law courses—a “suite” ranging from introductory basics to advanced and even cutting-edge legal work.

Key Players and Practitioners

Freeman teaches administrative law, environmental law, legislation and regulation, and natural resources law. Several other faculty members, including Assistant Professor Matthew Stephenson ’03 and Tyler Giannini, the clinical director of the Human Rights Program, teach related courses. And, when he arrives from the University of Chicago in the fall, the newly hired Cass Sunstein ’78, who has a strong interest in environmental risk and regulation, will join them.

The program also relies on a cadre of visiting practitioners renowned in the field. One of this year’s visitors, Roger Ballentine ’88, was a key White House adviser on climate change during the Clinton administration, and is widely recognized as a leading expert on the subject. In his seminar this past winter, students benefited from extensive interaction with guest experts, including U.S. Sen. and former Democratic presidential nominee John Kerry, who lectured and fielded questions for nearly two hours. Kerry, says Ballentine, was one of the earliest national leaders on the issue of climate change and is an expert in his own right.

A New Clinic

Another major goal was accomplished in 2007 with the launch of an ambitious new clinical program (see related story). Under the direction of Clinical Professor Wendy B. Jacobs ’81, students now have a broad array of opportunities to work on complex environmental law projects and cases. Some are off campus with government agencies and nonprofit organizations. Others are on campus, under Jacobs’ supervision—working on what she describes as “cutting-edge, real-time projects and cases.” A sampling of the projects includes greenhouse gas litigation; fighting false and misleading “green” product claims; a proposal for a permitting regime for ocean energy projects; and development of a liability framework for carbon capture and sequestration here and in China.

In a similar vein, Freeman has launched the biannual Junior Scholarship Workshop, in partnership with the environmental law programs at Berkeley and UCLA, to enable young scholars to submit their research and writing for critiques by seasoned academic mentors. The Environmental Law Program has also been a boon to HLS’s Environmental Law Society and the Environmental Law Review. Students have turned to Freeman and Jacobs for strategic advice and ideas, says the review’s managing editor, Matt Krauss ’09. Funding from the program has enabled the Environmental Law Society to hold more events, invite more speakers and send more students to high-level environmental conferences across the country, says Eric Ritter ’09, the society’s president. In January 2008, the Environmental Law Society and the National Security Law Society co-sponsored a talk at HLS by former CIA Director R. James Woolsey on the relationship between national security and climate. Says Freeman: “I know I’ve got a successful event when the groups that think they’re right-leaning and the groups that think they’re left-leaning co-sponsor it with equal enthusiasm.”

Startup Venture

Looking ahead, Freeman and Jacobs say there’s much more that they want to do. “We need people who believe in this program model,” says Freeman, “one that focuses on a wide range of regulatory tools, cares about business and seeks to engage students who are not already self-identified environmentalists. We need people who believe that Harvard Law School can have more of an impact than any other law school, who will be willing to finance it as it gets off the ground.” The program is a startup, she says, and it needs venture capital. With Kagan’s enthusiastic backing, she has logged thousands of miles flying around the country to drum up support.

What would the school do with the money? Hire more faculty members to further strengthen teaching and scholarship. Expand the clinical program by adding staff attorneys. Dedicate a full-time policy person to convene high-level events and engage with policy-makers in Washington, D.C., and the states. (The ELP now relies on an environmental law fellow—a paid student position—to help plan events and coordinate speakers. So far, Miriam Seifter ’07 and Meghan Morris ’08 have done so ably, Freeman says, but the impact of the position could be leveraged.) More money for additional staff would also make it easier to achieve another goal: injecting environmental law into the entire law school curriculum.

“We need people to help us draft curriculum ideas and think about little modules—a set of examples that you could integrate into other courses,” says Freeman. “What if we developed a set of materials for the bankruptcy courses about the relationship between environmental problems and bankruptcy? What if we designed a set of materials for the securities course that could expose students to environmental liability issues?” she asks, adding that lawyers will increasingly be expected to advise their business clients about legally mandated environmental disclosures.

As the program grows, Harvard Law School is putting the full force of its influence and talent behind solving the problem of climate change: In April 2008, the school held its second major conference on environmental law in two years, “Carbon Offsets: Opportunities and Challenges for State Carbon Trading Schemes.” In addition to scholars, the 18 panelists included representatives of state agencies, environmental organizations, industry and the banking sector.

For Freeman, bringing all of these interests to the table is essential. It reflects the kind of program HLS is building: cooperative, interdisciplinary and innovative. And it mirrors what’s necessary to thwart disaster and protect life on Earth.