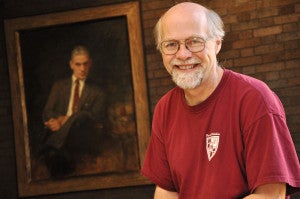

In September 1985, I stopped by Griswold 3S to pitch an LL.M. thesis idea to Professor Morton Horwitz. I was not committed to the topic: “Biography of the Reasonable Man.” My true goal was to view, at close vantage, a remarkable group of unreasonable men—the Crits: the Conference on Critical Legal Studies. Mort the Tort was one prong of the Unholy Trinity—three young leftist professors rocking and roiling legal education.

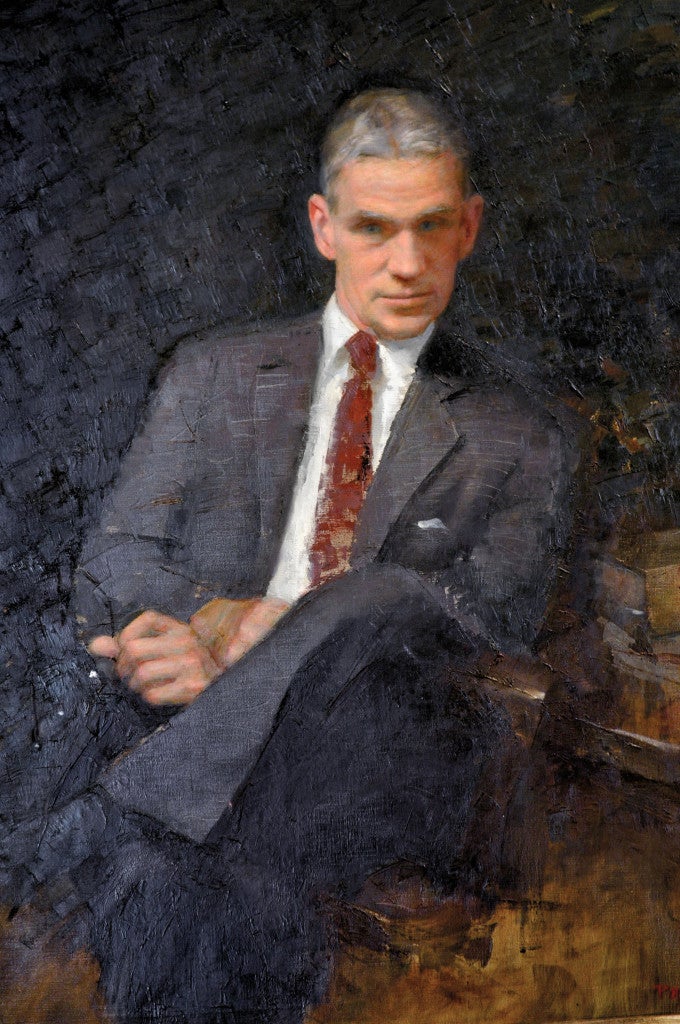

Waiting outside the office, I could not take my eyes off of the forceful, mysterious gaze of the man in the portrait on the wall. When Mort came out to greet me, I told him how much I admired the painting. “That’s Mark De Wolfe Howe,” he said, “the first Warren Professor. I’m the second.” He admired both the portrait and the man portrayed. Howe, a civil rights activist, had been the official biographer of Justice Holmes—although, at age 60, Howe died unexpectedly, leaving the biography unfinished.

Mark De Wolfe Howe (1933-1967), by Polly Thayer, 1970

Mort took me into his office and soon agreed to direct my thesis. After two months’ research, however, I realized that the Reasonable Man had lived too long—unreasonably long for an LL.M. thesis. Mort suggested an alternative, an independent paper on the evidence writings of James Bradley Thayer, an HLS professor from 1874 to 1902 best known for producing the first casebook on constitutional law and a theory of judicial review which influenced the likes of Hand and Brandeis. I took him up on the idea.

After my LL.M. year, I returned to teaching in Houston. Things got hot. By summer, tenure was out the window. One day, when I was wondering how I was going to feed my family, the phone rang—deus ex machina. A quavering voice identified the speaker as Polly Thayer Starr. We had never met, but I had heard about her—Quaker convert, renowned painter, and generous patron to HLS, where her grandfather, father and brother had been professors. Would I return to Cambridge, she asked, on her dime, to research the life of her grandfather?

More than 20 years later I ask myself, How was it that I was lifted out of the oily swamp and delivered up to the city on the hill? Mort cannot say, with certainty, how he chose the Thayer topic. My current hypothesis is that the handwriting was on the wall. The Howe portrait that arrested my attention that first day is signed “Polly Thayer, 1970.” Mort had known who the painter was all along, but I did not notice the signature until years later. By then, I had basked in Polly’s warm aura—at her Hingham estate, at the Quaker meetinghouse in Cambridge and at shows of her work on Newbury Street. And by way of her fond recollections, I had met her father (Dean Ezra Ripley Thayer) and brother (a Roman law specialist).

You can imagine, then, the black frame of mind I fell into when, walking through Griswold 3S three years ago and gazing at the fateful wall, I saw … a Kandinsky print called “Black Frame.” My friends in Special Collections said Howe was in a holding cell, getting ready to be ferried over the River Charles to the Depository. I felt the rustication ill-conceived. Why replace a talented, local woman’s portrait of a beloved teacher with a Rorschach card? And ill-timed. Ever-benevolent Polly had just died, at 101. I wrote out a clemency petition. Mort would sign, as would Professor John Mansfield, who had been Howe’s best friend on the faculty. Another denizen of Griswold, Professor Christine Desan, joined the rescue mission.

I wish I could say the crusade was arduous and dangerous; in fact, it ended before I could even circulate the petition. It’s true, we never dislodged the Kandinsky from 3S, but that was a good thing. From his old perch, Howe would be glaring at a coffee machine. Now, he has found a higher place. In 4N, he crosses glances with Thurgood Marshall. This seems apropos. For decades, John Mansfield administered the Mark De Wolfe Howe Fund, supporting legal history research and civil rights activities by HLS students and graduates. The memorial service for Howe in Memorial Church, in 1967, John recalls, ended with the great gathered throng singing “We Shall Overcome.”

The thrill of the rescue inspired me to look into the history of the painting. It seems that after his death, Howe’s students raised money for a portrait, but the funds disappeared. In 1969, Howe’s sister Helen wrote family friend Polly Thayer, mentioning the lost funds and wondering if she might do a portrait of Mark “out of love.” Polly was moved by this plea, and she completed the painting, gratis, in 1970. John Mansfield recalls walking up the stairs to Polly’s Back Bay garret backward, so anxious was he that the portrait would be unacceptable. But the moment he turned around and looked at the canvas, he saw his old friend again.

[pull-content content=”Jay Hook is a member of a research team — directed by Visiting Professor Daniel Coquillette %SQUOTE%71 — at work on a history of HLS due out by the school%SQUOTE%s bicentennial in 2017. Hook is now interviewing members of the Crit rebellion. Like Howe, at 60, he is the author of an unfinished official biography; his book will cover the three generations of Thayers on the HLS faculty. Meanwhile, he also represents indigent defendants in Middlesex County.” float=”center”]