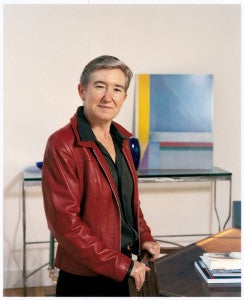

Janet Halley, an authority on legal issues surrounding gender, identity, and sexual orientation, has been appointed professor of law at HLS.

“Janet Halley is one of the nation’s leading scholars of the law, politics, and theory of sexual orientation and group identity,” said Dean Robert Clark ’72. “She is renowned for her work in family law, the theory of social movements, and law and culture. She is both an experienced attorney and a bridge between the worlds of law and literary criticism. I am delighted that Professor Halley has chosen to continue her exciting and important work as a member of the Harvard Law School faculty.”

Most recently professor at Stanford Law School and a visiting professor at HLS last year, Halley brings a literary background to her teaching of the law. She praises the opportunity for the “rich exchanges between legal studies and the humanities” at HLS and Harvard University. Before gaining her J.D. from Yale Law School in 1988, she taught English for five years at Hamilton College after earning a Ph.D. in English Literature from UCLA in 1980.

“My literary critical background has shaped the way that I study legal questions,” she said. “I tend more than some of my colleagues to see a legal event as a social text that can be read.”

For example, Halley cites the government’s policy on gays in the military as an evolving text, all versions of which must be read to understand their full ramifications. The policy was revised four times in 1993, according to Halley, and each change blurred the line between conduct and status. According to Halley, the result has been “interpretive paranoia.” One woman in the military told Halley that women in her unit feared being discharged if they had short hair and a black watchband because that had become a sign of lesbian conduct.

“The wool was pulled over people’s eyes. That policy is worse than people think,” said Halley, who wrote Don’t: A Reader’s Guide to the Military’s Anti-Gay Policy (Duke University Press, 1999). “In regulating sexual conduct, the policy regulates sexual status. You have to be a patient reader to see that.”

Halley is currently working on a critique of sexual harassment laws. She expects that she will recommend an elimination of the distinctive legal idea of sexual harassment in order to return to a focus on sex discrimination.

“I’m amazed at what’s going on in the whole landscape of sex harassment,” she said. “From a queer theoretic perspective, what we have now looks repressive and even possibly unfeminist.”

In her teaching, Halley examines “identity politics” as it relates to legal contexts. With Colorado’s ballot initiative Amendment 2, for example, which called for “no protected status based on homosexual, lesbian, or bisexual orientation,” lawyers on the pro-gay side argued that homosexuality is an immutable characteristic because it is genetic, according to Halley. Such a controversial stance, she says, betrays the pitfalls of claiming rights based on a gay identity. “I always felt the claim that ‘I can’t help it’ wasn’t a very dignified way of affirming one’s erotic projects,” Halley said.

Halley conceded that many people would disagree with her—including many feminists and gay-friendly thinkers.

“My idea of what we’re supposed to do with tenure is to use our brains and not hold back on what we think is right to say just because someone can co-opt us,” Halley said. “I’m delighted to have my new colleagues and this wonderful university and the smart students here to learn from and learn with. That’s what I’m here to do.”