For two decades, Professor Carol Steiker ’86 and her brother, Jordan Steiker ’88, a law professor at the University of Texas, have focused their careers on the death penalty, whether in the classroom or through scholarship, litigation, and law reform projects.

It is a passion they both absorbed in the chambers of Justice Thurgood Marshall, a fierce critic of capital punishment for whom they both clerked a couple of terms apart in the late 1980s.

In their latest collaboration, the Steikers have co-written a new book, “Courting Death: The Supreme Court and Capital Punishment,” in which they argue that the Court has failed in its efforts to regulate the death penalty since Gregg v. Georgia, its 1976 decision that allowed capital punishment to resume.

The Bulletin asked the Steikers what the future is likely to hold for capital punishment.

You note in the book that just six states conducted executions in 2015 and only three had two or more. Do you expect that the footprint of the death penalty will narrow any further?

Carol: It has shrunk so much that it’s hard to imagine it can shrink much more without disappearing. I don’t think it will expand, given the incredibly high cost of capital prosecutions, the left-right coalition questioning the practice, and the difficulty of obtaining lethal injection drugs. Given all of these dynamics, which are showing no signs of shifting, I think we should expect either continued shrinkage or continued marginalization of the practice even in states that authorize it.

Jordan: The decline in death sentencing is not only more dramatic but more telling than the decline in executions. It suggests fewer executions going forward and much less political commitment to the process.

You suggest it might be possible for the states that still have the death penalty to make improvements to how it is administered—by limiting the number of aggravating factors, for instance. Or is that a nonstarter politically?

Carol: It’s possible that could happen in a few states, but only in states that are on the road to abolition rather than states that are committed to the practice. History has shown over time that there’s inexorable pressure to expand the list of aggravating factors. Criminal justice administration is driven by anecdote: Something terrible happens, and lawmakers pass the equivalent of a Megan’s Law. One of my students took a picture with his phone while working in New Orleans, where he noticed a sign in a taxi that said it’s a capital crime to kill a taxicab driver in Louisiana. You see that dynamic constantly. Courts say the death penalty should be reserved for the worst of the worst, but the opposite has happened in the 40 years since Gregg.

From Harvard Magazine

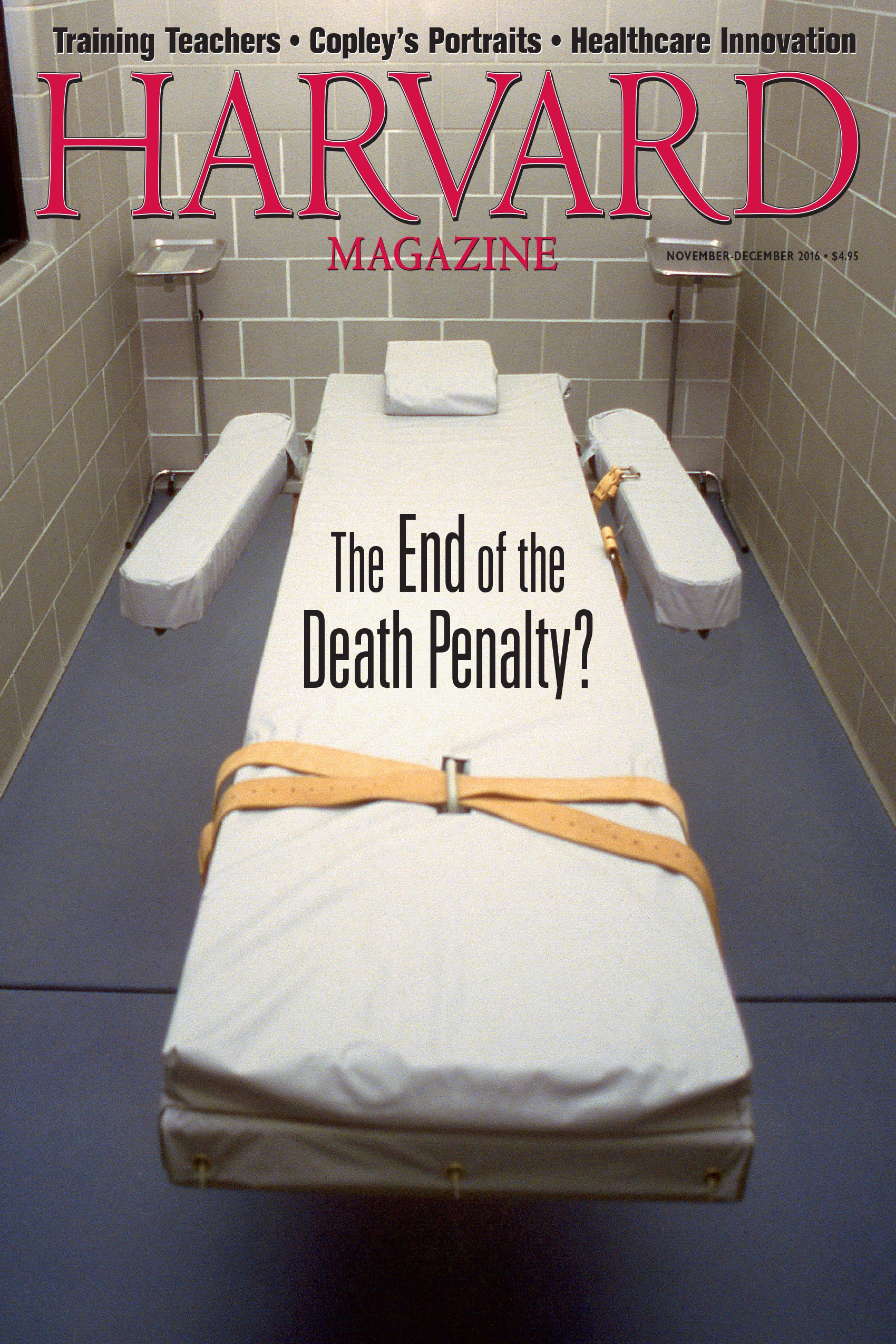

Death Throes: Changing how America thinks about capital punishment

By Lincoln Caplan ’76

Fifty years ago, American support for the death penalty was as low as it has ever been: more Americans opposed it than approved it. Violent crime in the country was low. The number of executions annually was a small fraction of the historical peak in the 1930s. These conditions set the stage for the modern era of the death penalty in the United States.

Read the entire article in the November-December 2016 Harvard Magazine

You predict a trajectory heading toward a “categorical constitutional abolition.” Is that a matter of years or decades away?

Carol: In the book we predict abolition within two decades, assuming that the Court either remains where it was politically before Justice Scalia’s death or moves further to the left.

Jordan: Around the world, one common path to abolition has been first to abolish the death penalty for ordinary crimes and then later to abolish it for treason or other crimes against the state, which in the contemporary world is terrorism. In the United States, the federal death penalty is so anemic, such a small part of American death penalty practice, that we might bypass this two-step process.

VIDEO: On Oct. 27 as part of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Series on Violence and Non-Violence, Harvard’s Mahindra Humanities Center hosted a discussion with Carol S. Steiker and Jordan M. Steiker on their new book. Additional panelists included Charles Fried, Beneficial Professor of Law at HLS.

What might be some of the consequences of abolishing the death penalty for the broader criminal justice system?

Carol: The death penalty tends to shine a spotlight on the inadequacies of the criminal justice system. If a case is not capital, it is hard to get as much attention, even where there is an egregious miscarriage of justice.

Jordan: On the other hand, the end of the death penalty might contribute to further reflection on the extraordinary punitiveness of our criminal justice system more broadly, and open the door to political and legal challenges to other prevailing practices.

The popularity and prevalence of the death penalty ebbed and flowed in the last century. Could you foresee renewed calls for its return post-abolition if there is a similar surge in violent crime in the future?

Carol: We view the death penalty as in a terminal decline. In the 1960s and 1970s, when crime was rising, the Court had not yet attempted to regulate the death penalty and fix its many shortcomings, whether racial discrimination, wrongful convictions, or arbitrariness throughout the process. Now, we’ve had 40 years of “mend it, don’t end it” that have been spectacularly unsuccessful. So even were we to face rising crime rates, there wouldn’t be the same naive optimism that we can make the death penalty work for us, because we’ve had all these years of it not working well at all.

Jordan: So many times throughout our history, the death penalty appeared to be moving in one direction, and then it shifted or transformed. One notable lesson of the history of the American death penalty is the sheer unpredictability of those movements. But for all the reasons Carol said, we believe the death penalty is in a terminal decline and there are many institutional conditions that make its revival very unlikely. But who would have predicted this election cycle and the shifting political climate we’re living in now compared with just a year ago? So it’s best to remember the wisdom of Yogi Berra about the difficulty of making predictions, “especially about the future.”

On Nov. 18, a multi-panel conference sponsored by the Criminal Justice and Policy Program at Harvard Law School explored themes in Professors Carol Steiker and Jordan Steiker’s new book, “Courting Death: The Supreme Court and Capital Punishment.” Topics for discussion included race and the American death penalty; constitutional regulation; and the criminal justice system. Donald B. Verrilli Jr., former Solicitor General of the United States, held a question and answer session for conference participants. Video of the entire conference is available in the playlist below or you can watch on YouTube. For more information, visit the website of the Harvard Law School Criminal Justice Policy Program.