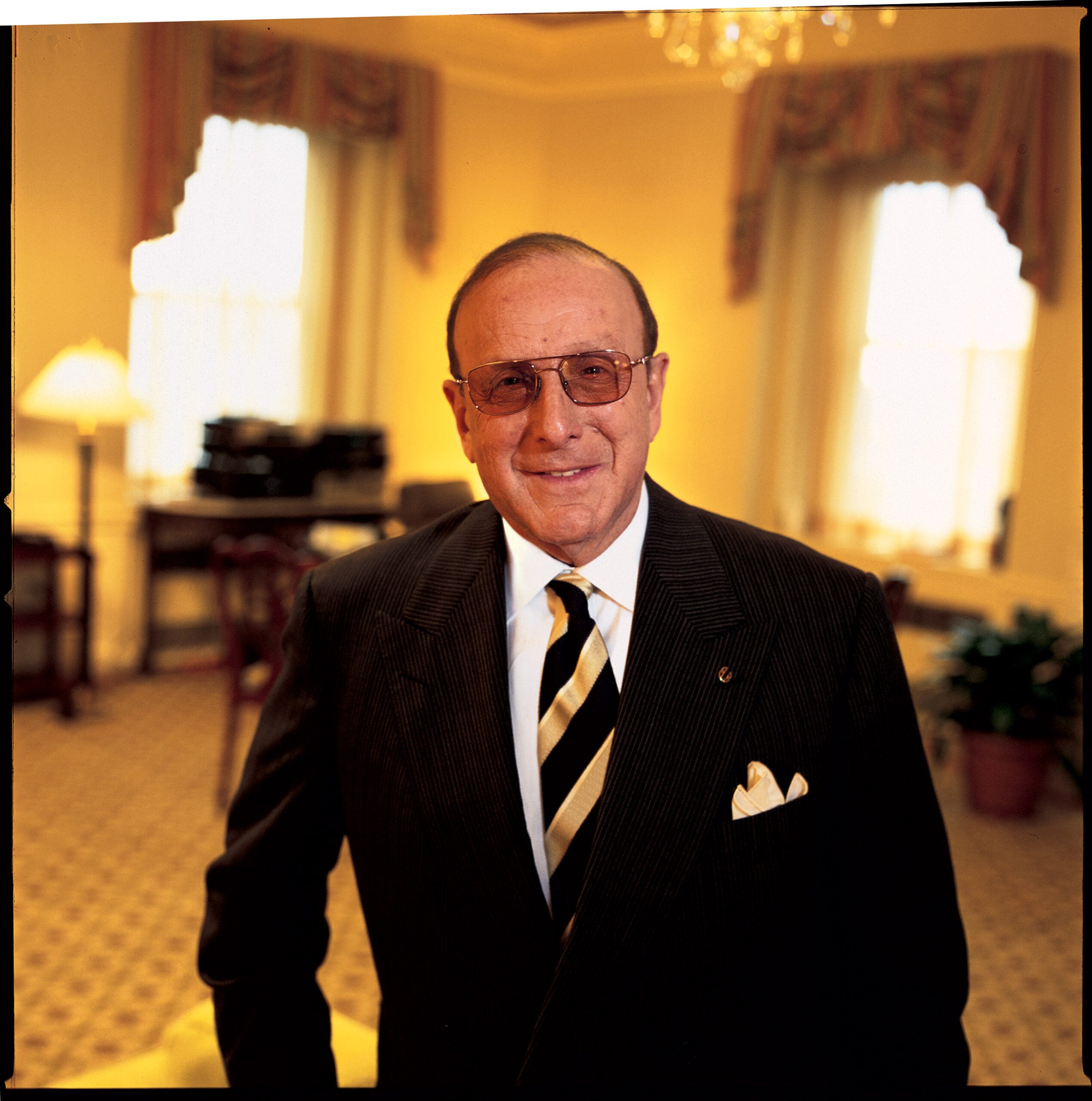

After 25 years at Arista Records, Clive Davis ’56 hopes the hits will keep on coming.

“It was the most vigorous year of uncertainty that I’ve ever had in my life.”

Clive Davis ’56 was not talking about the past year, when the music executive was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame while reports swirled about the end of his 25-year reign at Arista Records. The time was long before Clive Davis discovered and signed a coterie of talent that reads like a Who’s Who of recent music history. Indeed, it was long before Clive Davis knew a thing about music.

It was during his first year of Harvard Law School, when achieving the one and only career goal he ever envisioned for his life–becoming a lawyer–seemed even more precarious than discovering a multiplatinum artist. It was then that a Jewish kid from a working-class background in Brooklyn found himself for the first time living outside New York, in an elite institution, surrounded by students molded by the best preparatory schools, and feeling the pressure to maintain a B average to keep his HLS scholarship.

“I had so many adjustments at the time, it was hard to single one out,” said Davis. “This change was magnified by the campus of Harvard and the different nature of the student body.”

Davis kept his scholarship at HLS, buoyed by the knowledge that education was a means to “rise above your station.” That meant, to him, becoming a lawyer. For what else could a young man from a modest background, who spoke well, who studied hard, do?

He would soon find out.

* * *

Today, Clive Davis lives high enough in the sky to see beyond Brooklyn from his midtown Manhattan penthouse. He is 67, an age when he may be expected to look back at his career and the successes that afforded him his luxurious surroundings. And he will gladly recount those flush times, as well as some tough times, though he reserves his greatest passion for considering the times ahead.

The press, however, has focused on the recent times. Many media outlets reported that Davis was engaging in a high-stakes imbroglio last year with BMG Entertainment, the corporate parent of Arista Records, which declined to renew his contract as head of the label. Many artists praised Davis and some criticized BMG for its treatment of him.

But for Davis, the entire story can be synthesized in one word: Business.

Credit: Roger Ressmeyer/CORBIS Clive Davis admires the performance of Aretha Franklin in 1981. Davis has been credited with reinvigorating Franklin’s career in the 80’s.

“I certainly have had to live with a few months where the speculation was puzzling, and the facts were very simply those of business,” said Davis. “There was never a question that BMG wanted a major involvement with me. That was never up for grabs.”

At issue, said Davis, were his contract, his age, and his equity stake in Arista. Davis cited the retirement policy of Bertelsmann AG, the media giant that counts BMG as one of its units; executives in the company’s German headquarters must retire at 60. As the end of his contract approached last year, Davis said BMG balked at signing him to a new deal with Arista because of his age. In addition, according to Davis, the company devised a succession plan that did not reflect his partnership interest in Arista.

Nevertheless, Davis emphasized that BMG from the beginning wanted him to remain with the company, offering him a lucrative corporate chairmanship. It was not the first time he had such an offer; years before he was asked to become chairman of Warner’s music group. His answer to both offers was the same.

“For me–loving music–to be on a corporate level is not what I [want to] do,” said Davis.

Instead, Davis eventually accepted a deal from BMG that gives him a 50-percent equity stake in a new record label that was launched in October. Called J Records, after Davis’ middle name, Jay, the label boasts more than four times the financing of any other newly formed record company, according to Davis. In addition, the company is stocked with many top-level executives from Arista and has also acquired several artists formerly with the Arista label. Davis late last year announced the signing of Luther Vandross, who, like Santana, will create an album featuring a variety of other performers.

The new venture, Davis said, makes him “feel as excited and buzzed about music and what I do, and the process and the challenges and the creative opportunities, as I ever did.” Davis had other offers, from Internet companies to competing record companies. But nothing compared to the opportunity to start a new company, particularly after enjoying a final year of unprecedented profits at Arista, he said.

“It’s better to try to reinvent it with this kind of momentum than to try to top a billion [dollars] in worldwide sales,” Davis said. “And I was able to have a situation where I owned 50 percent of the company, so this is not only with no regret, but it is a far better business than every other kind of deal imaginable.

“There were companies offering me different combos of artists [and] unbelievable offers to compare and choose from. I hope that at the end of any contract you have these opportunities. I never felt beleaguered or uncertain.”

Davis founded Arista in 1974 and built it into a company that he estimated would be worth $3 billion on the open market. The label made an immediate impact with a number-one hit from Barry Manilow, grew with the record-breaking debut of Whitney Houston, and, as of late, is basking in the success of the Carlos Santana album Supernatural, one of the best-selling albums in history and a musical concept whose very idea was shaped and nurtured by Davis. After he saw Santana play at Radio City Music Hall, Davis knew that the musician still had the skills that made him a guitar god in the ’60s. But it’s not the ’60s anymore, and Davis, who has always prided himself on keeping current in music trends, conceived a way to turn a legend into a phenomenon.

“I felt that someone who had his virtuosity, that if we made a radio-friendly album, Santana could reemerge. [But] never to the extent to which it’s soared,” said Davis. “So I did architect a blueprint that half the album would be him doing radio-friendly Latin-African rhythms in the tradition of ‘Oye Como Va’ and ‘Black Magic Woman’ and ‘Evil Ways,’ and I would be entrusted with the other half, which led to the [songs] ‘Smooth’ and ‘Maria, Maria,’ and Dave Matthews and Everlast cuts that became the hallmarks of this all-time album.”

At the Grammy Awards ceremony in February last year, Davis won three awards for producing Santana’s and Whitney Houston’s albums in addition to winning a lifetime achievement award. The event marked one of three capstones to Davis’ career, all occurring nearly simultaneously. In March, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. And in April, he presided over a star-studded 25th-anniversary celebration of Arista, later aired on NBC, in which artist after artist sang their hits, and also sang th” praises of the man responsible for the record company. Yet before Arista Records was even born, Davis was already a force in the music business.

* * *

Davis achieved the goal that he set when he went to HLS. He began his career in a small law firm, which he chose over a big firm to “get out of that factory kind of assembly line of performance.” Yet the firm lost its major client a year later and was forced to lay off Davis and other associates. He didn’t know it then, but it was the best thing that could have happened to him, for he found a new job at Rosenman, Colin, Kaye, Petschek and Freund. The firm trained him in estate planning, contracts, tax, and corporate law. It also indirectly led him to the music industry.

“That is where luck plays a role in your life,” said Davis. “You’ve got to seize the opportunity if it is presented to you, but without question I could have gone to any one of hundreds of firms.”

CBS, one of the firm’s clients, owned Columbia Records, which offered Davis a position in its law department with the opportunity after a year to become general counsel. The offer meant not only more money, but a chance to work in a more entrepreneurial environment, according to Davis. Though he had never considered the record business, he soon learned that he had found more than just a job.

“It was a crash course in learning the totality of the business,” said Davis. “And so I just plunged in the same way I plunged in at school. Never taking anything for granted, and using hard work as the mechanism to trigger opportunities. I plunged in and found that I love music. Found that I loved what I did, and that I was consumed by it and I couldn’t get enough of it. And it contrasted with my previous experience, which was, quote, work. This was work but it was the awakening to what was to become a life’s passion.”

That passion catapulted him to the presidency of CBS Records in 1967, a year in which he truly grasped the power of a musical revolution. That year Davis attended the Monterey Pop Festival and heard the whiskey-soaked voice of Janis Joplin and knew, as Bob Dylan (another Columbia artist) once sang, that the times they are a-changin’.

“It obviously became a turning point in music,” he said. “It was a society-changing event as far as the people who were attending, coming out of Haight-Ashbury, questioning tradition and lifestyle. It was the electrification of music and the amplification of what had been pretty much acoustic before that in the folk-rock area. So it was eye opening and exhilarating at every turn. Obviously capped memorably by the discovery of Janis Joplin.”

In a position for the first time to discover and nurture artists, Davis signed Joplin. She wanted to mark the momentousness of the occasion in a way befitting her spirit, and the spirit of the times. So she offered to have sex with Davis. “I don’t think it became a trend,” Davis said drolly.

Though Davis politely declined Joplin’s offer, he soon made a name as a record executive who became intimate with his artists. Not in any social way, Davis emphasized, but by building relationships with artists based on a mutual love for music and an ear that could bring out the best in their songs. With Joplin, for example, Davis helped shape her first hit single, “Piece of My Heart,” urging her to repeat the chorus of what became her signature tune.

Other artists that Davis brought to the Columbia stable included Blood, Sweat and Tears, Chicago, Santana, Billy Joel, Bruce Springsteen, and Pink Floyd, which he signed for the bargain price of $300,000 before the group made the top-selling album Dark Side of the Moon. The record company—known for its aversion to rock or pop music before Davis’ presidency—doubled its share of the market in three years of his leadership. After a decade in the business, Davis had become the preeminent record executive of the era.

And then he was fired—not only fired, but literally escorted out the door. CBS alleged that Davis had used company money for personal expenses. Davis denied the charge, which came amid an unrelated governmental investigation of payola and other alleged violations within the record industry. According to Davis, an employee of the record company forged documents with Davis’ name and stole company money. When confronted, the employee tried to implicate others in the Columbia Records division in order to exculpate himself, Davis said.

“[CBS] had no idea whether these charges were true or false, but they were very concerned about their network license,” Davis said. “There was a new president who had only been there a few months who I didn’t know and, notwithstanding the fact that on a legal investigation there was certainly no wrongdoing, panic set in and this was the solution. I was expendable. So was that shocking? Was it traumatic? Yes. A whole year or year and a half where you can’t say a word because your lawyers are telling you you’ve got this governmental investigation going. The company arbitrarily was protecting itself, but on a personal level it was pretty hopeless.”

After writing a best-selling autobiography, Davis eventually pleaded guilty to one count of tax evasion—not because he did anything wrong, Davis said, but in order to spare himself and his four children from a highly publicized trial. Plus, he wanted to devote his time to the launching of a new company: a label he named after his secondary school honor society, Arista Records.

* * *

Clive Davis is listening to Dido Armstrong sing in a hotel room in London. It is 1997; she had been lead vocalist for a British band and is trying to launch a solo career. Almost no one in America knows her name. Until Davis listens.

In fall 2000, blocks away from Davis’ penthouse in Manhattan, a music superstore adorns its windows with a larger-than-life poster of Dido Armstrong. Her debut album, No Angel, has gone gold.

This is what Clive Davis likes best about his job.

“Certainly that first appraisal, to be able to spot a unique talent and say yes,” he said. “And then to see that artist become a worldwide success. There’s a lot of steps in between, you know. So it’s hard to leave out the process. But the discovery is the most exciting.”

He has done the same for Whitney Houston, 19 when he saw her for the first time performing in a club; Barry Manilow, an unknown opening for Dionne Warwick; and Bruce Springsteen, who played for Davis in his office before playing in any arena. They, and other artists he has signed and cultivated over the years, differ in musical style but share one important attribute, he said.

“You look for stars. You look for the makeup of [artists] who can have long-lasting careers and who could be headliners,” said Davis. “At the 25th-anniversary show of Arista, you would go from Santana to Barry Manilow to Sarah McLachlan to Annie Lennox to Puffy [Combs] to Aretha Franklin to Whitney Houston and Patti Smith. And the common thread is that they’re stars and each one would come out and take the audience off its feet.”

More stars are out there, people whose names nobody knows–for now. Clive Davis knows he’s going to find them.