Geraldine Umugwaneza LL.M. ’05 doesn’t think she could live in the Rwandan village where her family was murdered. After the 1994 genocide, the looting and violence left her mother’s house a frightening shell. But what scares her more is the idea that even today the neighbors might kill her, too.

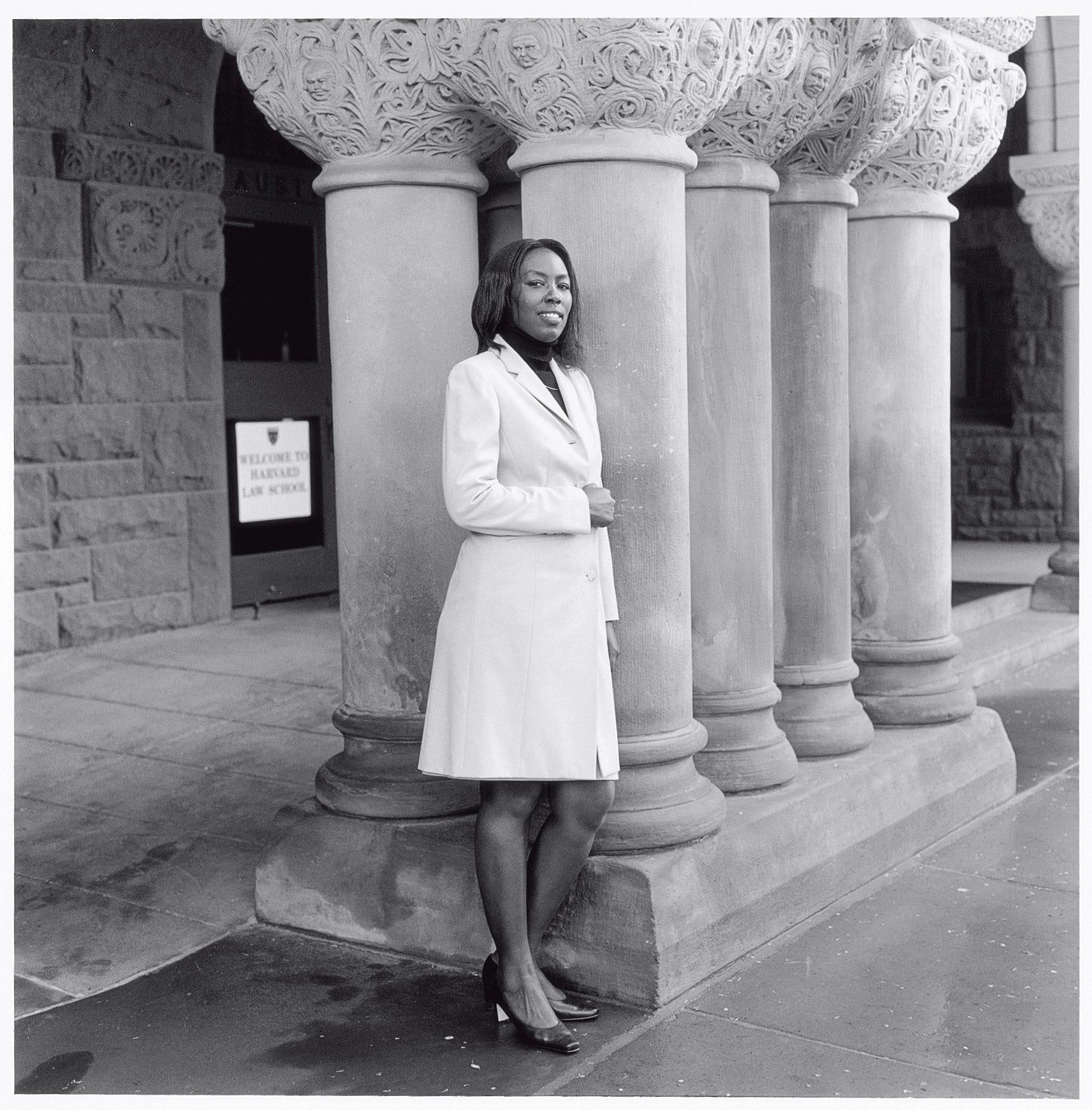

That a former Supreme Court judge should have such fears says a lot about the challenges that face Rwanda.

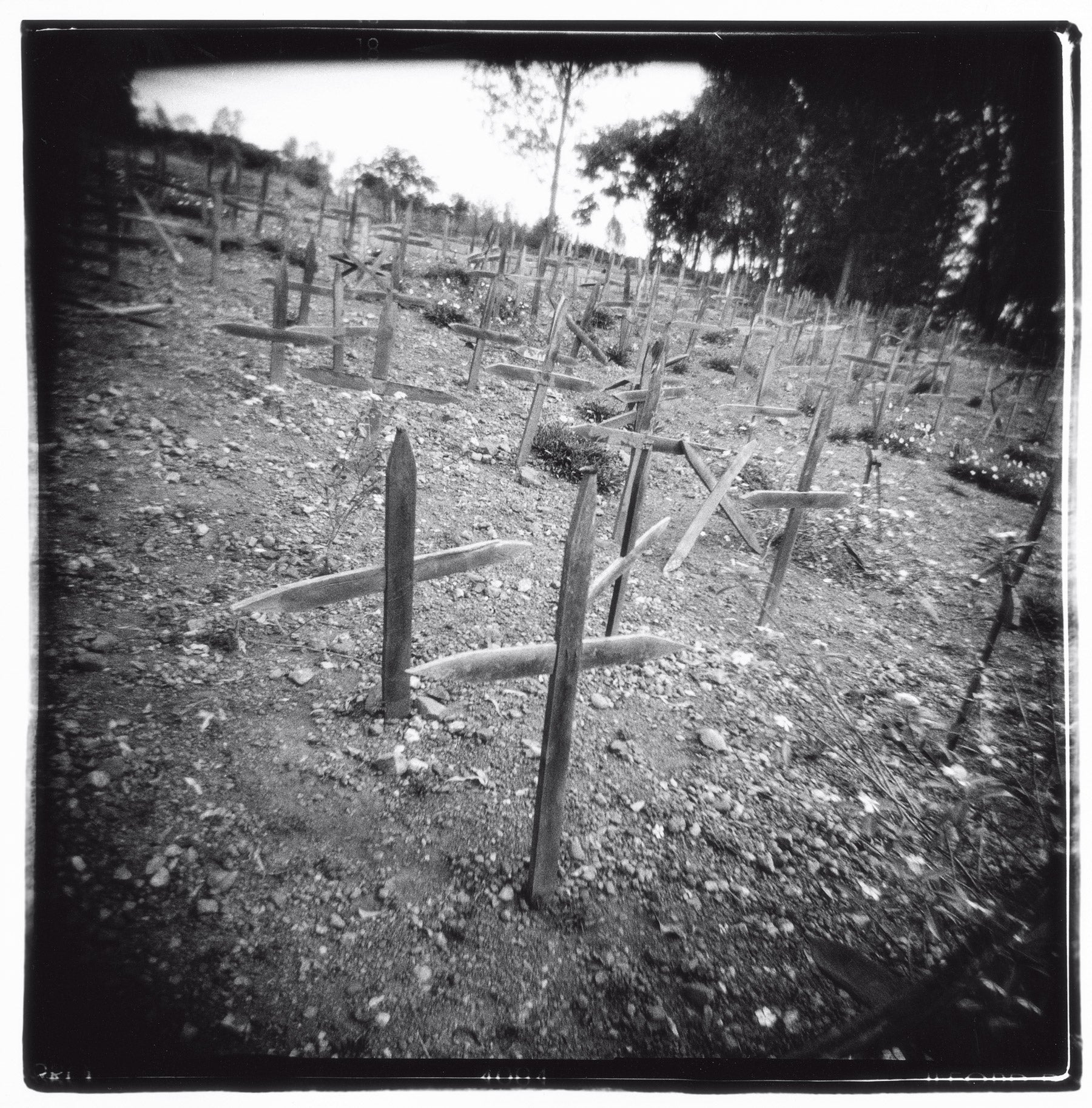

The government estimates that as many as 1 million people– one-eighth of the population–participated in the 100 days of killing directed by Hutu extremists against at least 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus. In a country where so many who were victimized live in proximity to so many who are complicit, how do you seek justice?

Umugwaneza believes it’s her obligation to try. Born a refugee in Uganda, she dreamed of the day she would go home to claim her identity. Violence against Tutsis had driven her parents from Rwanda in 1973, and it wasn’t until 1984 that her family took a chance on moving back. Umugwaneza stayed on in Uganda with one of her sisters to finish her education. By the time she crossed the Rwandan border, at age 20, the genocide had taken the lives of her mother, grandmother and four of her siblings. It left her driven to help put her country back together.

After studying law at the National University of Rwanda, she started by advocating for thousands of widows of the genocide. Most of the women had been raped and many had HIV or AIDS. By 1996, about 70 percent of the remaining population was female, yet women had no right to inherit property or hold bank accounts. Umugwaneza is happy she played a role in changing the law. “They looked at me as a daughter,” she said. “I felt it was something I had to do.”

At the same time, the Rwandan government was struggling with what it had to do to respond to the genocide. Faced with an enormous backlog of prisoners awaiting trial, and few lawyers and judges (many had been killed), it drew on a traditional form of dispute resolution that promotes reconciliation between the perpetrator and the community, and offers a reduction of sentence for those who come forward and admit their crimes and ask for forgiveness.

Umugwaneza first served as a technical adviser to the Supreme Court, which was supervising the new “gacaca” (pronounced ga-CHA-cha) system, named for the grass where the traditional hearings took place. In 2002, when she was 28, she was appointed a judge in the chamber of the Supreme Court charged with implementing the program. She traveled to villages across the country where people were selected to serve on the local courts and hear testimony in front of the community in open-air hearings. There are now close to 12,000 such courts in a country about the size of Maryland. This spring, as Umugwaneza was finishing a paper on the courts as part of the LL.M. program at HLS, the first gacaca trials were held.

Umugwaneza explains that the system works in tandem with the conventional courts. As evidence is gathered, the crimes are classified. The majority of defendants, mostly those accused of having done the killing, are tried in the gacaca courts, where the maximum sentence is 30 years. The cases of those accused of having planned or instigated the genocide, on the other hand, are passed on to the conventional courts, which can impose the death penalty. The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, in Arusha, Tanzania, also relies on the gacaca courts for building its cases.

Human rights observers have raised possible problems with the system, including intimidation of witnesses, lack of due process for defendants who are not represented by counsel and the fact that accusations against soldiers of the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front that now controls the government are being overlooked.

“Observers have understandably raised critical questions about the gacaca courts,” said Professor Henry Steiner ’55, director of the HLS Human Rights Program, “but the courts also open up possibilities for seeking justice after genocide or other mass atrocities.”

Umugwaneza knows the system has its flaws. But right now she believes it’s her country’s best hope. After a genocide, only so much truth can be known, she says. But the gacaca process, she believes, is getting at a lot of it.

She is all too familiar with the brutality of that truth. The gacaca courts are meant to facilitate reconciliation. But forgiveness, she said, is something that has to be talked about on an individual basis: “Most of us are finding it very, very difficult–almost impossible–to forgive and reconcile.”

Last year gacaca had not yet begun in the area where Umugwaneza’s mother and siblings had lived with her grandmother (her father had died of illness in 1990). But when Umugwaneza returned there last April, members of the community helped her identify villagers they believed had killed her family. Some of the suspects were already in prison. Some denied the allegations. But she heard how her mother and grandmother had been buried alive. How a killer chopped off her sister’s arms and left her to suffer before she was hacked to death. How her brother was burned. How her youngest sister sought refuge with a cousin whose husband gave the 8-year-old up to be killed.

“They were not strangers,” she said. “They were not strangers.”

By then she’d known for years that her family had been murdered, but that couldn’t prepare her for what she found when neighbors pointed to where the bodies were buried: “I wasn’t ready to see my mother again.”

Yet she did what was needed and dug where she was told.

Although she’s reburied her family’s remains in the village cemetery, the memories stay with her. Without her faith in God, Umugwaneza says, she could never move toward healing. As for forgiving the people who slaughtered her family: “I have kind of forgiven. But having forgiven–kind of–that doesn’t mean that I don’t want these people to be prosecuted.”

Rwandan authorities say that over the past three and a half years, 75 percent of prisoners have admitted to crimes with the hope of receiving reduced sentences. Many survivors find this hard to accept. But at least, says Umugwaneza, now there is accountability.

“People may forgive, and eventually may be reconciled, but people are going to be punished. And that is also an achievement, to hold people accountable.”

When Umugwaneza returns home, she’ll work again in public service. Steiner, who supervised her paper on the gacaca courts, called her “an extraordinary woman, with extremely valuable perceptions about ideas like reconciliation and forgiveness.” Umugwaneza says her year in Cambridge was a gift–not just to her but to her society.

The girl who was a refugee in Uganda has grown up to claim her national identity and the complicated legacy that it brings.

“We destroyed our country. It was in pieces,” she said. “What we are trying to do through gacaca, through the reconciliation programs, is to pick up the pieces of our country and put them together and once again build a nation.”