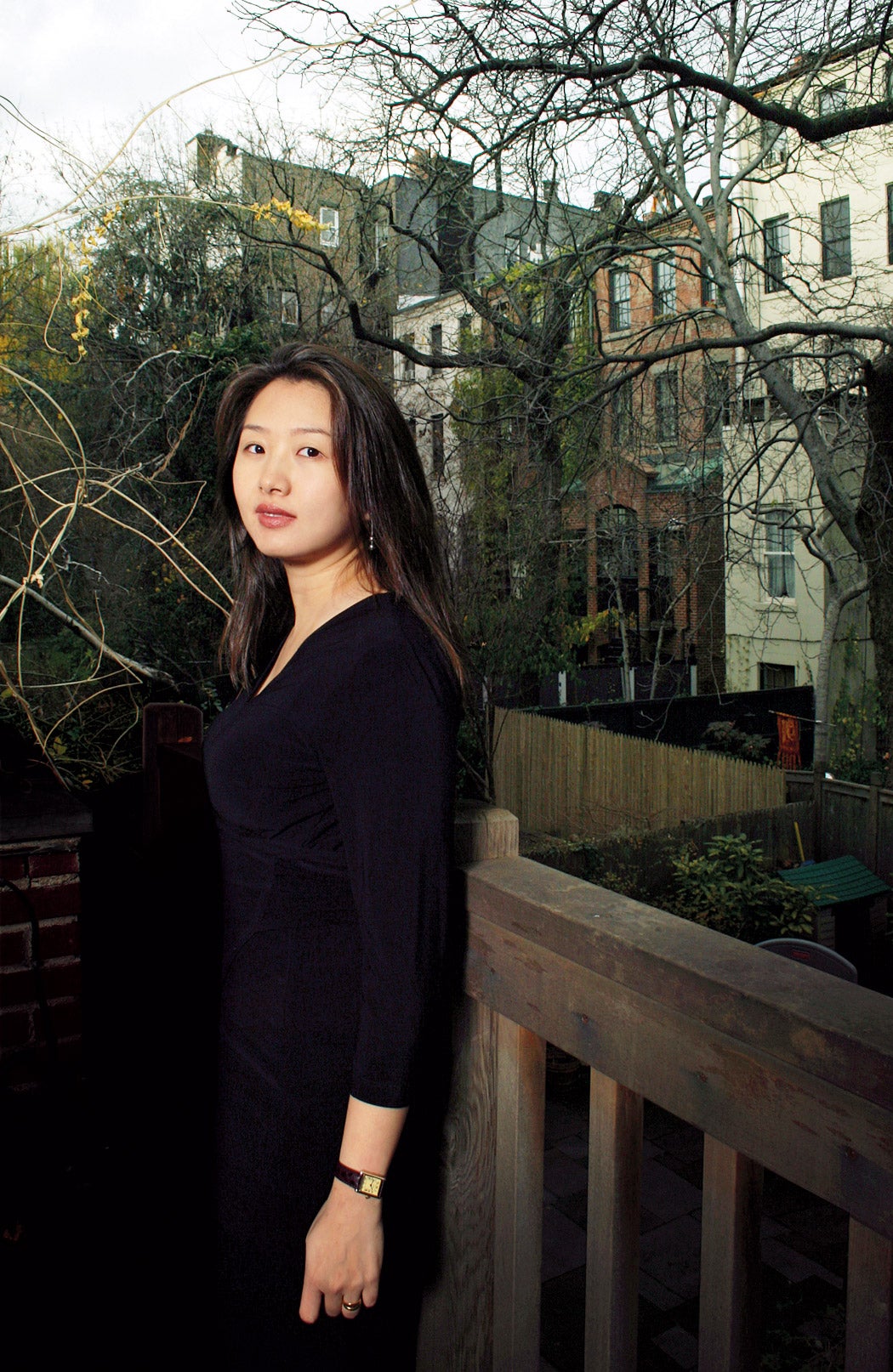

Over the past 30 years, feminists have struggled to make domestic violence a public issue—not just a family matter, but a crime recognized by the police and punished by the courts. But according to Assistant Professor Jeannie Suk ’02, in the process of correcting for shameful past inaction, the criminal justice system may now be too involved in private life. In a recent Yale Law Journal article, Suk takes a critical look at the use of protection orders. Who is being harmed, the Bulletin asked Suk, by these protective measures?

The criminal justice system’s growing control of the home harms women. The point of domestic violence protection orders—in fact, the point of legal measures against domestic violence—is to protect the autonomy of women.

When a woman seeks a protection order, you can be pretty confident that she believes it will improve her situation. But in many jurisdictions, the decision isn’t up to her. The moment a misdemeanor domestic violence arrest enters the system, prosecutors routinely seek a protection order banning the alleged assailant from the home whether or not the woman wants this. Then, in a standard exchange for a plea to a lesser charge or a plea that leads to dismissal, prosecutors might make that protection order “permanent,” essentially divorcing the couple.

Even if the woman asks her partner to come home, the relationship is illegal. The police may make unannounced visits to check that he isn’t around. His mere presence—even contact through a phone call—can result in arrest and imprisonment. In fact, that’s precisely the result the system seeks. It’s hard for prosecutors to prove violence when women won’t cooperate with the prosecution—especially in the case of misdemeanors, which don’t involve serious physical injury. But violations of protection orders are easier to prove. They become a proxy crime—a way of circumventing the burden of proof.

Frequently, women who are having their intimate relationships criminally prohibited by the state ask prosecutors not to intervene. Whose judgment on this is better—the prosecutor’s or the woman’s? Much law enforcement proceeds on the view that these women don’t know or can’t say what’s best for them because they are locked in a terrifying dynamic of abuse and coercion. I find that paternalism troubling when applied uniformly in a world of mostly misdemeanor arrests, especially considering that many women brought into the system are poor and, often, minorities.

Another problem is that there’s often no coordination between the criminal system and a family court that might deal with issues that arise when you separate a couple. Excluding a husband from the home may mean there is nobody to pay the rent and the bills. So imposing de facto divorce through the criminal system can be worse for the women than actual divorce, where alimony and child support can be set.

Now that we’ve had some success in getting domestic violence taken seriously as a public issue, it’s time to be vigilant that techniques of state control don’t negate the goal of that reform—to improve women’s autonomy.