When the COVID-19 pandemic brought the global economy to a near halt in March 2020, lawyers — like everyone else — wondered how the crisis would affect not only their health and personal lives but also their work lives.

For private law firms, there were fears the crisis would significantly impact their financial security. Would legal work dry up? Would there be widespread layoffs at law firms? To the surprise of almost everyone, 2020 ended up being the best year that many law firms had ever had — followed by an even better year in 2021. Per-partner profits at the largest U.S. firms rose 13% in 2020, according to Am Law’s annual report, and close to 20% in 2021. Lawyers found themselves billing more hours than ever before under once-unthinkable circumstances, including working from home during lockdown and litigating trials online.

At the same time, the pandemic created enormous pressure for the services of legal aid organizations that provide free or low-cost legal representation. According to the HLS Office of Clinical and Pro Bono Programs, the number of inquiries from people seeking legal aid has more than tripled since 2020.

In the past several years, seismic events have intersected in powerful ways and contributed to huge demands for legal services, says Professor David Wilkins ’80, faculty director of the Harvard Law School Center on the Legal Profession, a research organization dedicated to providing a deeper understanding of the rapidly changing global legal profession. He cites the global health crisis; a complex global economic crisis born of the pandemic and other disruptions including the war in Ukraine; and increasingly urgent calls around the world for social and racial justice, sustainability, and economic equality. Globalization, technology, and demands for social justice — significant trends before 2020 — became “turbocharged,” Wilkins says, by the pandemic and other events that year, including the murder of George Floyd.

Seismic events have intersected in recent years and contributed to huge demands for legal services.

As a result, companies, government entities, and individuals turned to lawyers for help on things like the government stimulus packages that drove trillions of dollars into the economy, the wave of bankruptcies that took place during the pandemic, labor and employment matters, and the pressure companies have increasingly faced from stakeholders to take a formal stand on issues of public note.

“All of these issues are landing on desks of lawyers in law firms, in-house legal departments, and government offices,” says Wilkins. “The pandemic and related issues have highlighted the importance of law and lawyers — in fact, the rule of law has never been more important.”

J. Tracy Walker IV ’90, managing partner at McGuire Woods, which has 21 offices in the U.S. and abroad, has experienced some of the trends Wilkins describes. While deal work and litigation were down through most of 2020, deal work picked up considerably toward the end of that year, and the firm saw increased demand throughout 2020 from many of its longstanding clients, particularly those in heavily regulated industries such as big banks and utilities, Walker says. And 2021 saw a “huge uptick” in many practice groups including private equity, health care, debt finance, securities, and employment litigation. The demand for the firm’s services “was so high that we had significant concerns about lawyer burnout,” he says.

Demand for pro bono and low-cost legal services put immense pressure on the public interest sector as well. “The intense stresses of the pandemic — the fear, the isolation, the losses of jobs, routines, and people — were especially difficult for people in our client communities,” says Esme Caramello ’99, faculty director of the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau and a clinical professor of law. “People who were barely able to afford rent to begin with now really had no way to pay it; people with moldy and roach-infested apartments had to stay inside them 24 hours a day; tensions rose in already-violent relationships; co-parenting became fraught because of fears of spreading a deadly disease; and low-wage immigrant workers became even more vulnerable to mistreatment in the workplace when so little work was available.”

Government aid programs during the pandemic, including unemployment and rent assistance programs, were “desperately needed,” adds Caramello, but difficult to navigate without a lawyer’s help.

As levels of social and economic uncertainty rise, lawyers — both private and public sector — are increasingly called upon to help their clients and their organizations navigate those uncertainties to achieve their economic and policy goals,” says Scott Westfahl ’88, director of HLS Executive Education. In the executive education programs over the past two years, “private- and public-sector lawyers have been sharing with us that they have never felt more stretched, or more needed, in their organizations. General counsel and law firm leaders are expressing that they are both exhausted but also proud of the impact they have been able to have in the past two years.”

The toll it takes

Though perhaps not facing the challenges of those most severely impacted by the pandemic, many lawyers nonetheless found themselves, at its height, working from home, supervising children unable to go to school, and dealing with health issues, their own or others’. And even before that, the younger generation of lawyers, like other millennials, was already resisting long-entrenched elements of practicing Big Law, such as brutally long hours. Over the past two years, leaders in the legal industry have worried more about how to attract and retain top talent.

In particular, Westfahl notes, some of the partners he’s spoken with have emphasized that they must address the “record attrition rates, burnout, and mental health and family challenges that working remotely imposed on their associates,” adding, “What we’re concerned about is sustainability” from a quality-of-life perspective. In the fall, Wilkins and Westfahl are launching a new HLS Executive Education program, “Leading the Law Firm of the Future,” where they will be providing frameworks and ideas for law firm leaders to adapt their business models toward what they are calling “sustainable profitability,” says Westfahl. In other words, profitability must be reconciled with a healthy working environment.

For lawyers, the challenges wrought by the past two years give us “an exciting opportunity to be engaged in really the most pressing issues facing our world today,” says Wilkins, who is vice dean for Global Initiatives on the Legal Profession at Harvard Law School. “But it’s also a challenge because lawyers and law firms or legal departments have had to fundamentally adapt and change the way in which they’ve always operated” — primarily, by working remotely instead of in an office with colleagues, holding meetings online, and learning how to try cases and present hearings effectively via Zoom or other online platforms.

“Ultimately, I think it’s going to be an exciting time for our students and graduates because I think there’s going to be a lot of change,” Wilkins says. “A lot of that will be good and exciting change — although, like all changes, it may have its painful and rocky moments.”

As many companies and schools have returned to in-person life, Wilkins and others at CLP are examining which innovations from these past few years are worth retaining. Moving some aspects of the judicial process online, for example, can help to make justice more affordable and accessible. But does that mean all courts should migrate online?

“Everyone is really struggling to understand what this new world is going to look like, and there’s no answer,” at least not yet, he says. “At the Center on the Legal Profession, we are trying to do a number of things we hope are helpful.”

There’s one thing of which Wilkins is certain. “No one,” he says, “thinks we’re going to go back to the way it was in 2019.”

Adapting to online adjudication

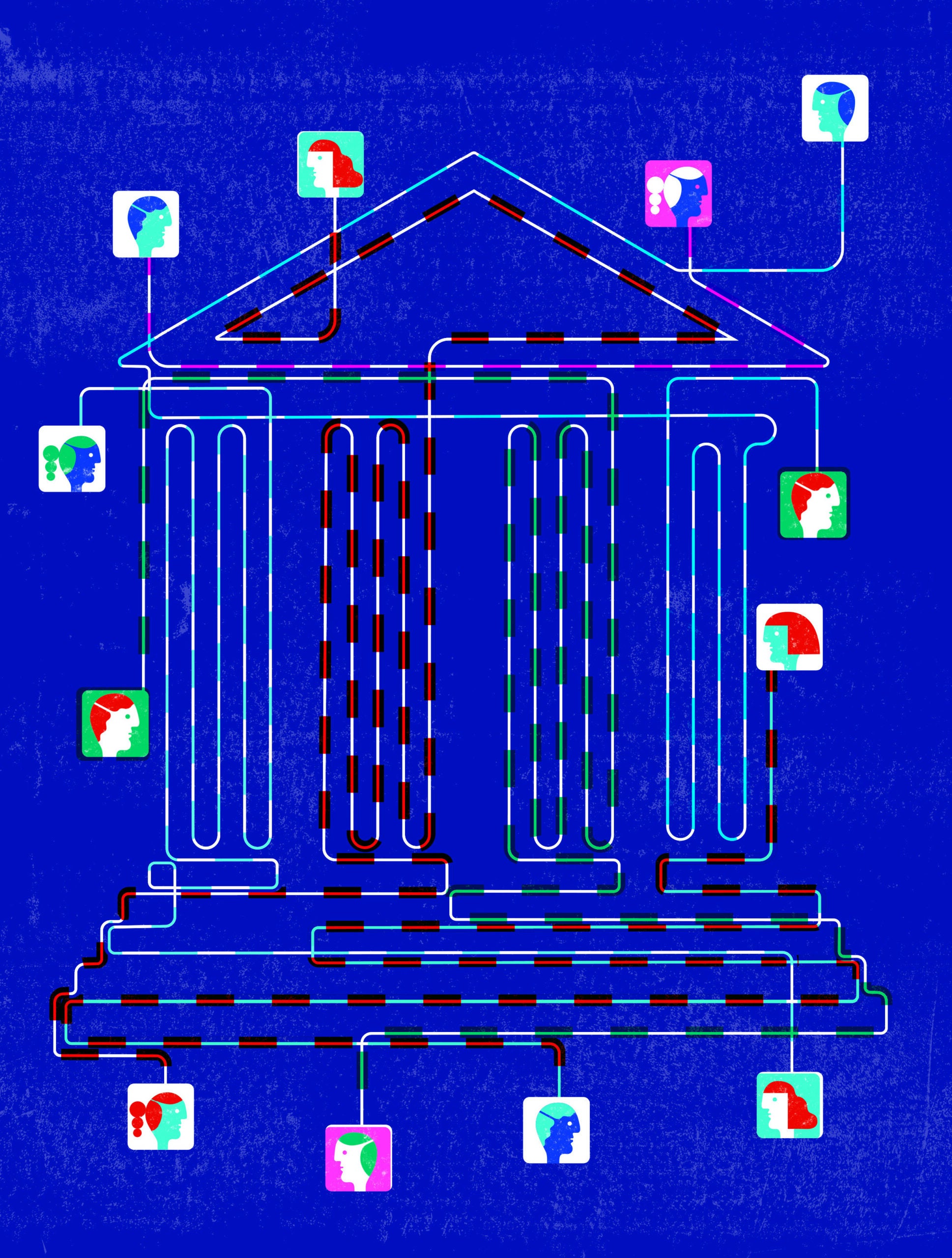

For a profession renowned for its resistance to change, the transformation from in-person to virtual legal practice was surprisingly swift. In April 2020, the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act authorized federal courts to hold civil and some criminal proceedings by teleconference. A month later the U.S. Supreme Court took the unprecedented step of hearing oral arguments via telephone.

According to empirical studies, judges and lawyers report being satisfied, for the most part, with video hearings during the pandemic, says Richard Susskind, an international expert on the legal profession and author of “Online Courts and the Future of Justice,” who collaborates frequently with Wilkins and others at the Center on the Legal Profession. On the other hand, online court proceedings were hard to access for many who don’t have the needed technology, including elderly people and low-income populations. Online litigation rules were also constantly changing, and the courts were moving slowly in the online format, says Caramello, so getting an abuse protection order or child support, for example, was “nearly impossible without a lawyer.” With legal aid organizations stretched thin, online adjudication may not, in reality, provide increased accessibility for everyone.

For a profession known for its resistance to change, the shift to virtual practice was surprisingly swift.

As the world tiptoes back from the worst of the pandemic and returns to some semblance of normalcy, industry leaders are working to identify which aspects of their work are best done in person and which are done well in the virtual world, “sometimes even better than in real life,” says Wilkins.

Litigators at WilmerHale, an international law firm with 1,000 lawyers, participated in a number of virtual civil trials in 2020, according to Jamie Gorelick ’75, a partner at the firm and deputy attorney general in the Clinton administration. “I really like oral argument online. It has advantages that outweigh the disadvantages, but trials are tough,” in part, Gorelick explained in a 2020 webinar presented by CLP, because it’s much harder to manage witnesses during cross-examination when you’re not in the same room.

Kathleen Sullivan ’81, a partner at Quinn Emanuel and chair of the firm’s national appellate practice, has engaged in a number of online appellate arguments since the beginning of the pandemic. She agreed that online oral advocacy offers some advantages. Having to fly across the country for a 15-minute oral argument is inefficient and costly for clients, she said in the webinar, and collaboration within a legal team, including sharing real-time impressions of the argument in order to make on-the-spot adjustments, is much easier online. Still, the advantages should be weighed against what’s lost. A Zoom or Teams hearing simply can’t match what Sullivan, quoting Susskind, calls the “majesty” of the courtroom setting, which impresses upon everyone, including the litigants, that their case is important.

Understanding the implications of that loss of formality also concerns Sanjana Parikh, a 2020 graduate of the University of California, Berkeley School of Law, who, as an exchange student at Harvard Law School in spring 2020, took the Legal Profession seminar taught by Wilkins and Bryon Fong, executive and research director of CLP. The class studied Susskind’s book on online courts, in which he argues that greater use of technology, including virtual courts, would greatly reduce case backlogs and improve access to justice.

Parikh, now an associate in the technology transactions and data privacy practice at Latham & Watkins in Washington, D.C., wrote a paper for the class that raised concerns about Susskind’s proposal. While she isn’t opposed to online court proceedings, she urges that their look and design be carefully considered — with input from jurists and lawyers (a point with which Susskind agrees) to retain the respect for the judicial system. “The visible markers that this is a temple or a hall of justice, a place where justice will be done, where people are treated equally — all of that, the black background on Zoom fails to capture,” she says.

Susskind doesn’t propose a full-bore replacement of all in-person courts but argues that for many kinds of cases, online courts — where the judge, lawyers, and litigants are all online — make a lot of sense. But judges and lawyers have traditionally been resistant — until the pandemic. At least 160 jurisdictions have been running courts remotely since the pandemic started, he notes. “I have no doubt that COVID has opened people’s minds to new ways of working, and changed some minds,” says Susskind, technology adviser to the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales.

Still, he adds, “It’s an oversimplification to say, without qualification, that [the pandemic] has fundamentally accelerated the uptake of technology.” Videoconferencing has been used in some courts since the 1980s, he points out, and he sees today’s online adjudication not as a technological breakthrough but as simply doing the same things in a different way. True technological breakthroughs in the legal industry — such as the use of artificial intelligence — have been backburnered for the time being because of the pandemic, says Susskind.

‘The most exciting time in the world to be a lawyer’

What is safe to say is that as the legal landscape expands, many young lawyers are questioning the traditional trajectories of career success. “The market for top talent has never been as global or as transparent as it is now,” says Westfahl. “In a global and transparent market,” he adds, people “can vote with their feet and move to other positions where they are more likely to find more of the balance they want. What we are also seeing is that more of them are opting to start their own businesses, which is a lot easier to do now with lower-than-ever barriers to entry for startups.”

“I think today’s best HLS graduates are not only looking for meaningful work to do but also conscious of the overall impact of the institutions in which they are working,” says Caramello. “To retain them for more than a few years, law firms will need to prioritize internal work on diversity, equity, and inclusion and reduce the work hours to give young lawyers a chance to build rich lives outside of work. They’ll also need to significantly improve their structural support for pro bono and social justice work and think harder about what they might refuse to do on behalf of paying clients.”

“I think the emergence of issues around sustainability and social justice and stakeholders is being driven in large part because millennials and now Gen Z are ascending into top positions throughout every aspect of our society,” says Wilkins. “This provides a space for new ideas and new approaches to solving what have been incredibly complex, intractable problems in our world, and a new energy around trying to find solutions.”

This past spring, Westfahl and Farayi Chipungu, an adjunct lecturer at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, co-taught the first-ever Adaptive Leadership course at Harvard Law School. Adaptive leadership “is particularly useful in times of uncertainty because it distinguishes between technical challenges — where expertise exists and you invest time, money, and resources to solve the challenge — and adaptive challenges, where the world is changing, and addressing the challenge requires a very different framework of leadership,” says Westfahl. “Our profession now faces many challenges that are much more adaptive than technical, such as how to create a more sustainable law firm business model, what the new world of work should look like, or how to make real progress on advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion across our profession.”

The good news, he says, is that the disequilibrium in the system caused by the disruption of the past few years has enabled more people to challenge the way things have always been done. At Kirkland & Ellis in Chicago, for example, Jaisel Patel ’20, who works in the area of mergers and acquisitions, works three days in the office and two days from home, an arrangement perhaps unimaginable at most big firms before the pandemic proved it was feasible. Though Patel says he is “not working less, necessarily,” the flexibility of working some days from home makes for much better work-life balance. “It’s been great,” he says.

Westfahl says he is “optimistic that we’ll see increasing progress on workplace flexibility, new business models, and greater advancement of women and people of color into leadership roles, in part because of the disruptions we have been facing.”

Wilkins agrees. “I tell my students,” he says, “that it’s the most exciting time in the world to be a lawyer because you can be part of these transformations.”