A desperately ill Minnesota man flies to Bangladesh to buy a kidney from a willing seller, rather than waiting for a donor and surgery at his local hospital. A parent in New York takes her severely autistic child to China for an unproven, even dangerous, experimental stem cell treatment that’s not offered in the United States. A dying woman in Maine flies to Switzerland, where a suicide clinic helps her end her life. An infertile couple in Florida have their sperm and eggs implanted in a woman in India whom they pay $4,000, a fraction of the price of surrogacy in the U.S. And a health insurance company urges its American customers to travel to Malaysia for cardiac bypass surgery, offering all kinds of incentives, including free airfare and hotel for them and a travel companion.

Comparison Shopping for Medical Care

According to some estimates, 2 million Americans a year are traveling overseas for major health procedures. Cost is the driving factor.

Hip Replacement

U.S. $75,000

India $9,000

Heart Bypass Surgery

U.S. $210,000

Thailand $12,000

Knee Replacement

U.S. $35,000

Singapore $13,000

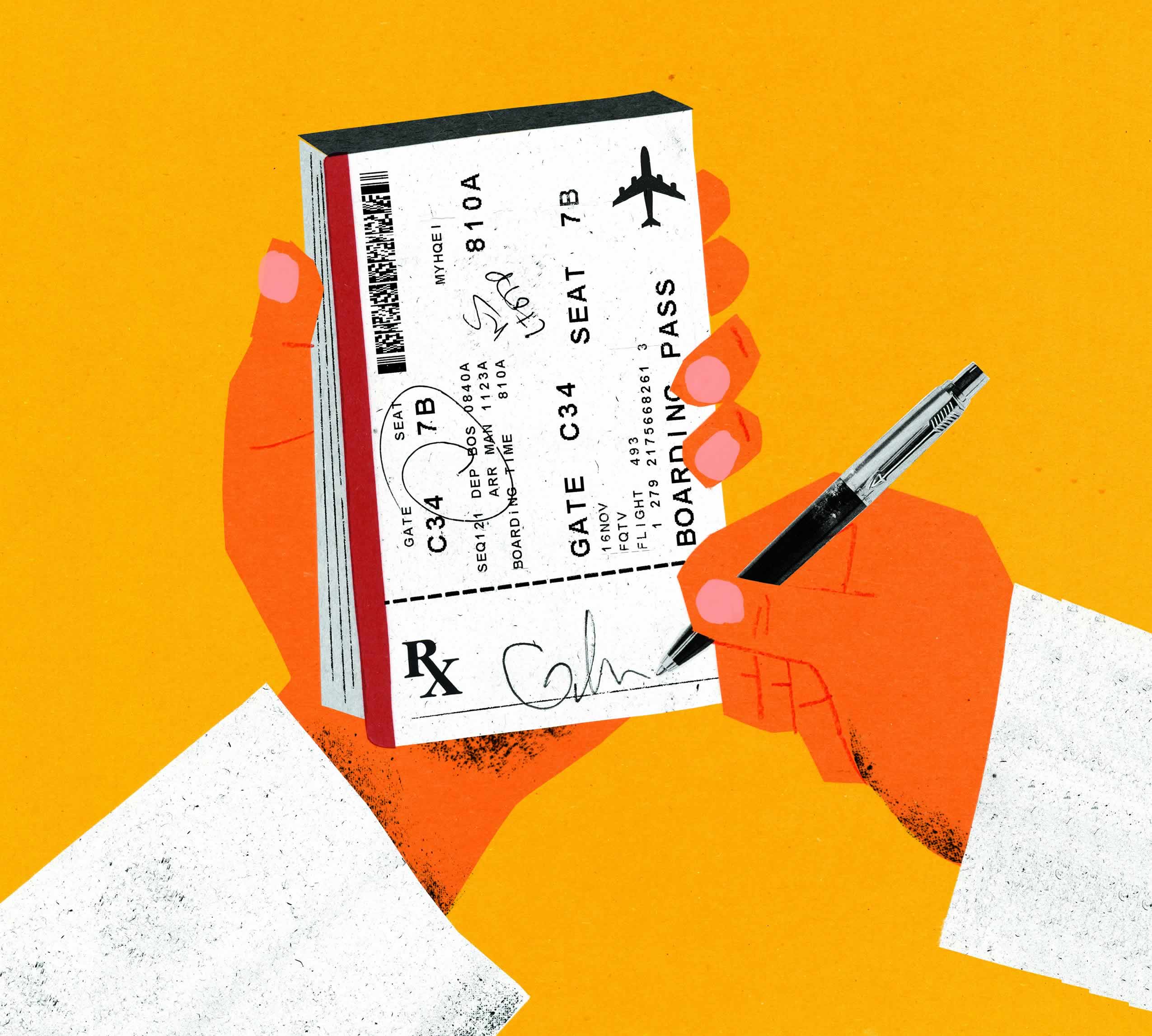

Medical tourism—patients traveling from their home countries to another destination for medical care—is completely transforming the health care industry as we know it. Once the province of the uber-wealthy seeking radical cosmetic surgeries or treatments unavailable in the U.S., medical tourism has become an attractive option for many, especially the uninsured, since the cost savings are so dramatic. According to some estimates, about 2 million Americans a year are traveling overseas for major health procedures, from knee replacements to neurosurgery, with the number growing rapidly. And with the advent of the Affordable Care Act, better known as Obamacare, medical tourism will increase as insurance companies look to cut costs, predicts I. Glenn Cohen ’03, a Harvard Law professor and one of the world’s leading experts on medical tourism.

The four largest commercial health insurance companies in the U.S. have already launched or are considering medical tourism programs. It’s possible that in a few years, a significant number of Americans will travel abroad for their medical needs, a prospect inconceivable a decade ago, when U.S. medical care was perceived as the gold standard, and the thought of surgery in Mexico or Brazil seemed dangerous and strange.

For Americans, this new willingness to go abroad for care is driven primarily by cost. By one set of estimates, the out-of-pocket price of a hip replacement in the U.S. is $75,000, compared with $9,000 in India; heart bypass surgery costs $210,000 here versus $12,000 in Thailand. Those tenfold or more cost savings may be impossible to resist. Insurance companies are eyeing foreign health care as a way to save money, with self-insured employers, and even state and local governments, also exploring this option. A knee replacement that costs an insurance company $35,000 in the U.S. runs just $13,000 in Singapore; even with the added expense of airfare and a hotel for the patient and a traveling companion, it’s a huge cost savings.

But money isn’t the only factor. Other nations may offer treatments or procedures illegal or unavailable in the U.S., such as assisted suicide, experimental procedures or new drugs that don’t have FDA approval. Stem cell therapy—unavailable in the U.S. but offered elsewhere—is a prime example of what Cohen calls “circumvention tourism,” or people traveling to other countries for treatments banned here. More than 200 hospitals in China offer stem cell therapies to foreign patients, with the largest provider, Beike Biotechnology, charging $30,000 per treatment.

With so much money to be made from all forms of medical tourism, it’s no surprise that countries around the globe are looking to get involved. “I think most people underestimate the size of the industry and how sophisticated and business-oriented it is. There’s a huge amount of money flowing through the system, and everyone wants a piece of it,” says Cohen, who recently returned from a conference in Malaysia, and has been contacted by government officials in Fiji for advice on jump-starting a medical tourism industry. “With the combination of a strong tourism trade plus low health care costs and existing hospitals, a lot of countries see an opportunity to make money,” he says. “India is able to charge [Americans] considerably more than what they do to their domestic population, but it’s one-eighth of what the charge is in the U.S.”

However, the growth of medical tourism is raising a host of ethical and legal concerns, from a fear of substandard care in foreign medical centers to the potential exploitation of the poor who sell their organs or rent their wombs. If wealthy Westerners travel to poorer countries for health care at high-end clinics that employ the best physicians, where does that leave the local population for its medical needs? And why are health costs so low elsewhere? Are health care workers exploited with low wages or unconscionable working conditions?

Determining the best way to approach these issues is the province of Cohen, who this year was promoted to a tenured professorship at HLS, effective July 1. He explores them in his writing but also in courses, such as the Health Law and Policy Workshop and his seminar on Reproductive Technology and Genetics: Legal and Ethical Issues. He is also in high demand by governments, private companies, medical centers, and others, as they look to legal and other problems related to this growing industry.

“The space Glenn writes in is new territory, where things are happening but regulations and laws may not have caught up,” says Katie Kraschel ’12, an associate in the health care industry team at Foley & Lardner in Boston, one of the top health care law firms in the country, and a former student fellow at the HLS Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics, where Cohen is co-director. “We weren’t looking at current policies and asking how we could change them, but rather, in places where there are no policies, we are asking, Should there be one? What would it look like?”

Indeed, in the area of medical tourism, there is little regulation, to date. Cohen believes it would be a mistake to simply ban the practice, since, for many uninsured people, that would cut them off from their only affordable option for nonemergency care.

But there are questions regarding the quality of foreign health care—and the rights of patients who are injured during medical treatment abroad. Right now, there is very little data, Cohen says, although one study found that the morbidity and mortality rates for cardiac surgeries at two hospitals in Thailand and India were comparable to those of the best hospitals in the U.S. In the just-released “The Globalization of Health Care: Legal and Ethical Issues” (Oxford University Press), edited by Cohen, author Leigh Turner examines media accounts and finds 27 reported deaths of patients who traveled overseas for bariatric and cosmetic surgeries; but it’s unknown how many successful surgeries there were.

“So the biggest problem is that we don’t know much about the quality of care,” Cohen says. “We like to think the U.S. is the very best, but it turns out there’s a huge gap in mortality and morbidity from one hospital to another, and one region to another, in the U.S. So even if a [foreign clinic] isn’t as good as the best U.S. hospitals, how is it compared to the average U.S. hospital?”

If a medical tourist gets a bad knee replacement or comes down with a serious infection following bypass surgery, she’ll have a very difficult time getting compensation for her injuries. For various jurisdictional reasons, the medical malpractice laws in the U.S. only rarely apply to foreign defendants; even if they do, the amount of damages is likely to be quite low. Jumping right into this market are new companies offering medical tourism insurance: If you’re headed to India for bypass surgery, you can purchase a $1 million policy for about $6,000, to protect you if something goes wrong, Cohen notes. And insurance companies sending customers abroad have a strong incentive to see them return healthy, so they don’t end up paying for long recovery times or repair surgeries. It’s in their interest to “channel” patients to high-quality clinics that meet standards that could be set by an accreditation board, he says. Another possibility is getting foreign providers to agree contractually to submit to the jurisdiction of American courts for the purposes of medical malpractice actions, in exchange for referrals.

As for some of the more troubling kinds of medical tourism—such as kidney transplants—there are other concerns. “The bread and butter of kidney sales involves poor people in slums, mostly in Asia but elsewhere, too, selling their kidneys in a gray market,” says Cohen, whose article “Transplant Tourism: The Ethics and Regulation of International Markets for Organs” appears in the Spring 2013 issue of the peer-reviewed Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics.

He will also discuss these issues (along with all other aspects of medical tourism) in the new book he is working on, “Patients with Passports,” due out next year from Oxford University Press. As he writes: In Baseco, a slum in Manila, in the Philippines, 3,000 of its 100,000 residents have sold a kidney. Kidney transplant tourism is on the rise primarily because of the widespread availability of cyclosporine, an immune-suppressive drug which has greatly enlarged the potential community of kidney donors; increased demand in the developed world; and the failure to mobilize enough kidney donation to make up the gap. Buyers are willing to travel to India or the Philippines because they can simply purchase an organ rather than wait for a donated kidney back home, which they may never get. There are disturbing aspects, including that many kidney sellers, who are promised around $2,000 to $4,000, don’t get their full fee, and often complain of lingering health problems. Still, as Cohen writes, it remains unclear whether banning this practice is superior to attempts at regulation; many kidney sellers may believe they are better off, all things considered. And an outright prohibition would drive the practice into a full-on black market, far more dangerous to buyers and sellers. “I don’t think we can eradicate these markets altogether,” he says. “While many regret having done it, after the fact, others feel they benefited.”

Stanley Chen ’14, who holds a Ph.D. in philosophy, is working with Cohen on his medical tourism research and appreciates his approach, which gets at “the really complicated questions related to normative arguments,” says Chen. “For instance, why exactly do we think organ selling is particularly egregious? And if you do think it’s a bad thing, how do you structure regulations to deal with it?” He adds, “As philosophers, we generally deal with conceptual questions. One thing I like about Professor Cohen is he tries to do both. He cares a lot about practical ethics.”

Among the questions is the potential exploitative effects of Westerners’ purchasing their health care in other countries. “Like any type of outsourcing, we have a social responsibility to think about the effects that this outsourcing has on citizens of other countries,” says Kraschel, who has written about fertility tourism, a subject also covered in Cohen’s work. In particular, she studied the issue of American couples choosing women in other countries, such as India, to be gestational surrogates, since the cost is about $4,000 versus $25,000 or $30,000 in the U.S. Sometimes, the women receive even less than they were promised, and Kraschel sees great value in regulation of the agencies facilitating these transactions.

Another area that is troubling involves the stem cell industry. While there’s no scientific evidence that stem cell therapy is effective except in treating a few blood disorders, says Cohen, doctors abroad attempt to use it to treat conditions including spinal cord injuries, multiple sclerosis and Down syndrome. And there are documented instances where it has induced dangerous tumors. A recent study on stem cell tourism found that 45 percent of patients are under the age of 18, which Cohen finds particularly disturbing. “These parents are desperate, and their children have serious disorders, but at the same time, the risks abroad are really great,” he says. “How should physicians deal with a parent who wants to take the child abroad? Should they consider reporting these parents to the authorities because there is precedent for treating this as child abuse? Is that a good option here?”

Cohen believes that taking thoughtful approaches to keeping medical tourism safe makes far more sense than driving it underground with unrealistic regulation that consumers will ignore. Accreditation of foreign medical providers is one important step. And American authorities should pursue consumer-law actions against clinics making false claims, he suggests, although it may be impossible to get personal jurisdiction over them unless they have a U.S. office. New issues and concerns will arise as medical tourism continues to grow; Cohen, and his students, will be ahead of them.