Ketanji Brown Jackson ’96 took a historic step on June 30, when she was sworn in as the 116th justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, the first Black woman to ascend to the nation’s highest court.

“I have dedicated my career to public service because I love this country and our Constitution and the rights that make us free,” Jackson said at the White House on April 8. “It has taken 232 years and 115 prior appointments for a Black woman to be selected to serve on the Supreme Court of the United States. But we’ve made it. We’ve made it. All of us.”

A day earlier, the U.S. Senate voted 53-47 to confirm Jackson to replace retiring Justice Stephen G. Breyer ’64, for whom Jackson had clerked two decades earlier. As she stood on the South Lawn with President Joe Biden, who nominated her, and Vice President Kamala Harris, Jackson said, “We have come a long way toward perfecting our union. In my family, it took just one generation to go from segregation to the Supreme Court of the United States.”

It also took a supremely illustrious career. An honors graduate from Harvard College and Harvard Law School, where she was an editor on the Harvard Law Review, Jackson clerked for Massachusetts U.S. District Court Judge Patti B. Saris ’76, Judge Bruce M. Selya ’58 of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit, and Justice Breyer. She was an appellate lawyer in the Office of the Federal Public Defender in Washington, D.C.; worked as litigator with a private law firm; and served as assistant special counsel to, and later, a vice chair and commissioner on, the U.S. Sentencing Commission. In 2013, President Barack Obama ’91 appointed Jackson to be a judge on the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. In 2021, President Biden appointed her to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, replacing Merrick Garland ’77 when he became attorney general of the U.S.

During her Supreme Court confirmation hearings, Jackson — who had been confirmed three times previously by the Senate, for her position on the Sentencing Commission and the two federal judgeships — “handled herself with such grace, and perseverance and focus” over three grueling days of an often-contentious hearing, said Kimberly Jenkins Robinson ’96, her law school roommate.

Only once did Jackson give a glimpse into the extraordinary pressure she was under, when Sen. Cory Booker invoked Harriet Tubman, who relied on a star to guide and inspire her as a conductor on the Underground Railroad. “Today, you’re my star. You are my harbinger of hope,” Booker told Jackson. “This country is getting better and better and better, and when that final vote happens and you ascend onto the highest court in the land, I’m going to rejoice. And I’m going to tell you right now, the greatest country in the world, the United States of America, will be better because of you.” At that, Jackson, who’d remained a picture of composure, pulled out a tissue and discreetly dabbed her eyes.

Lisa Fairfax ’95, a law professor at the University of Pennsylvania who was a college roommate of Jackson’s and is one of her closest friends, introduced Jackson at the start of the hearings. “Her excellence, not just in pedigree and resume and experience, but the way she carried herself throughout the process, only confirmed what we all thought she was: brilliant,” said Fairfax.

After the Judiciary Committee deadlocked 11-11, Jackson’s confirmation went to the full Senate, where three Republicans — Sens. Mitt Romney ’75 of Utah, Susan Collins of Maine, and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska — voted with Democrats to confirm Jackson. At a campus event organized by HLS Student Government, the Harvard Black Law Students Association, and the Harvard Women’s Law Association, dozens of students erupted in cheers when the vote was announced.

After the hearings, Nina Simmons ’95, a New York City lawyer who roomed in college with Jackson along with Fairfax and Antoinette (Sequeira) Coakley ’95, asked Jackson how she was feeling. “She said, ‘It’s a lot — it’s just a lot,’” recalled Simmons. “I think she meant that from a historical perspective and a personal perspective, she understands she has a great responsibility and how historic this moment is, and she does not take that lightly.”

What She’ll Be Like as a Justice

Harvard Law School Professor Carol Steiker ’86, herself a former public defender and a teacher of Jackson’s when the latter was a first-year student, said she is “delighted that someone with that professional background will be on the Court,” because “it’s just very hard for other people who have not had the intimate experience of representing people facing criminal charges” to have the perspective of understanding the real-life implications. Over a third of those serving on the federal judiciary are former prosecutors, while less than 7% were public defenders, according to a 2021 study by the Cato Institute.

Stephen Rosenthal ’96 was a classmate of Jackson’s in middle and high school in Miami, then at Harvard College and Harvard Law School. “The justices of the Supreme Court will see in Ketanji an incredibly serious, thoughtful, nuanced person who can be very forceful in her convictions, but also very reasonable and pragmatic in the way she approaches an issue,” said Rosenthal. Breyer, too, was a pragmatist, he said, but Jackson brings a “very different life experience,” as a Black woman in America and through her varied experiences with the criminal justice system.

Before she became a household name as a Supreme Court nominee, Jackson was best known as the judge who ordered former White House Counsel Don McGahn to testify before the House Judiciary Committee, after then-President Donald Trump argued that McGahn, as a former presidential adviser, had absolute immunity from doing so. Jackson rejected that argument, famously writing, “Presidents are not kings.” During her confirmation hearings, she was asked about those words, and explained, “Our constitutional scheme — the design of our government — is erected to prevent tyranny.”

Jackson won’t change the ideological makeup of the Court, which now has a “6-3 supermajority of conservatives,” even though Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. ’79 sometimes abandons the other conservatives, said Richard C. Schragger ’96, a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law, who has remained friends with Jackson since their days together on the Law Review. Schragger believes that Jackson, like many others, is concerned that the Court has become too politicized, which is affecting public trust in the institution, and feels that she will be attentive to this challenge.

“I can only imagine what it must be like on the Court right now, especially in the wake of this leak of the draft opinion overruling Roe v. Wade,” said Steiker in a May interview. “It’s going to be very tense, I imagine. But I think the student that I remember, and the incredibly impressive judge whom we all saw on our televisions during her confirmation hearings, is someone who is going to be able to avoid as much as possible that kind of … animosity that seems to pervade political divisions everywhere.”

Rachel Barkow ’96, vice dean and professor at New York University School of Law, who also served with Jackson on the Law Review and later on the Sentencing Commission, added: “What we absolutely can be certain of is she will be thorough, fair and unbiased, and very careful. She’s not a flamethrower, so don’t expect her to become some kind of firebrand on the bench. I think she meant it when she said [during the hearings] that she is a very careful reader of text. She’s an originalist, as she said; she cares about the original meaning and history of the Constitution; and she has respect for precedent. The only time we had a difference of opinion on the Sentencing Commission, I came out in favor of the defendant and she came out in favor of the government. That’s an indicator that she’ll go where she thinks the law requires her to go even if she doesn’t agree personally.”

‘Believing in the Promise of America’

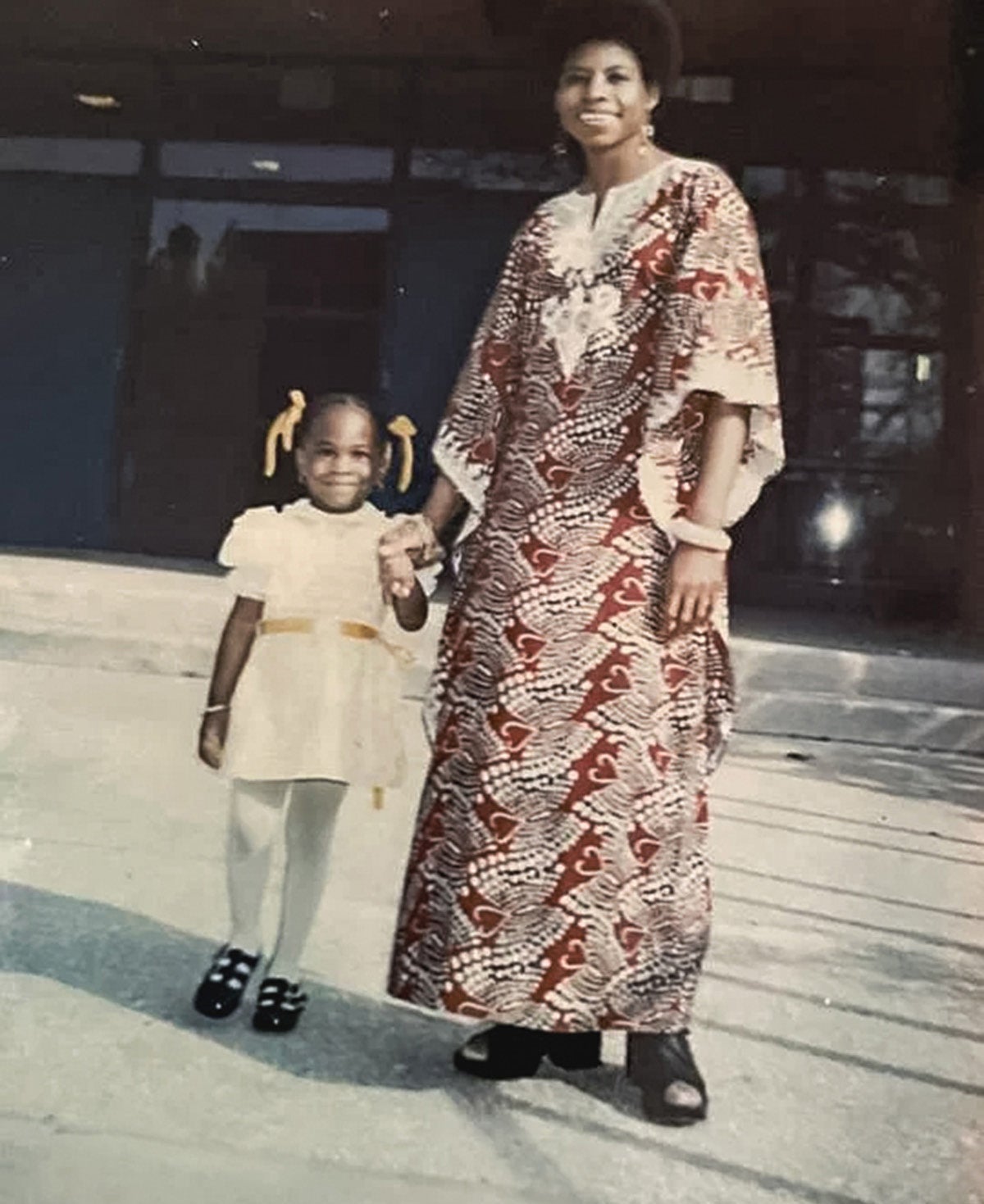

Born in Washington, D.C., Jackson was raised in Miami. Both of her parents were schoolteachers before her father went to law school and became attorney to the Miami-Dade County School Board, and her mother became a high school principal who was beloved, according to Rosenthal.

During their early years in college, Jackson sensed that her group of friends needed a break and invited them all to her parents’ home in Miami. “I think all of us were exhausted, feeling out of ourselves, not feeling comfortable, necessarily, with our Harvard experience,” recalled Simmons. “Her parents really took us in and made us feel at home and kind of loved us up. We got some of the strong support that she had her whole life.”

Another great supporter is her husband, Dr. Patrick Jackson, a surgeon whom Jackson began dating when they were undergraduates. “I remember Patrick coming to visit her” at the dorm at HLS, while he was in medical school, recalled Njeri Mathis Rutledge ’96, another friend from law school, now a professor at South Texas College of Law Houston. “He was downstairs, and I heard him say, ‘I love you, Ketanji.’ There was something so sweet about that moment that I’ve always remembered it.” The Jacksons have two daughters, Talia and Leila, who are “wonderful” and “level-headed,” said Simmons, “and that goes to not only their parents but their grandparents on both sides.”

Jackson was always “an incredibly dedicated student,” said Rosenthal, who was vice president of their high school senior class while Jackson was president.

“She was far and away the most successful member of our fairly illustrious speech and debate team,” he added, gaining a statewide and then national reputation, including during national competitions, some of which were held at Harvard. She was the kind of law student who read not only all the readings and recommended readings, but also all the footnotes and references in the footnotes, said Fairfax.

When Jackson was a trial court judge, Rosenthal’s law firm lost a case before her, and he argued the appeal. “Because she did such a good job in her opinion, it was like a nightmare to try to handle as the appellant,” recalled Rosenthal. “I lost the appeal, as I knew I would.”

“She’s extremely intelligent, probably one of the smartest people I know,” said Simmons, adding that parallel to her intellect, there’s an equally strong human side to Jackson: “She’s very warm and very funny. She does great impressions. She is hilarious. She’s a great dancer and she’s a fantastic singer with a great voice,” she said. Rosenthal and Jackson performed together in an improv comedy troupe in college, and Simmons recalled a college event where Jackson sang a Billie Holiday song wearing a flower in her hair like Holiday. “It was extremely powerful,” Simmons said. Not only is Jackson exceptionally talented but she’s “very humble about that. It’s that balance that so impresses people.”

Her friends also emphasized her kindness. Minutes before their lengthy 1L civil procedure final exam, Jackson reminded Rutledge to bring extra pencils and a cushion. “She cares about other people,” said Rutledge. When Jackson was going through the Judiciary Committee process for her first judgeship, Simmons was diagnosed with cancer. “She just appeared on my doorstep in the middle of everything she was going through,” she said. And during the grueling Supreme Court nomination hearings in April, Simmons and other close friends were texting with Jackson. “We were trying to keep her spirits up, and she’s asking about our families and our kids,” Simmons said. “That’s how she’s always been.” In early May, Fairfax was visiting Jackson, and instead of discussing the historic nature of Jackson’s confirmation or the enormous demands of her new position, “We spent most of the time talking about me and catching each other up on our families,” Fairfax said. “That’s typical of Ketanji.”

22 of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 116 justices (nearly 19%) attended Harvard Law School

Jackson has been an elected member of the Harvard Board of Overseers and, before that, an elected member of the Harvard Alumni Association, so her “roots and her engagement with Harvard run deep,” said Roger Fairfax ’98, dean of American University Washington College of Law, who knew Jackson at HLS and is married to Lisa Fairfax.

When Jackson’s name began to surface as a possible nominee this winter, Simmons and others gathered, in just three days, hundreds of signatures of support from Harvard alumni. “Many people really love her,” said Simmons.

“I just feel like a lot of people wish her well,” said Schragger. “It’s nice to see someone from Harvard Law School Class of ’96 be appointed to the highest court in the land, and I can’t imagine a better person than her to do it. … It’s good for us and it’s good for the country.”

At the White House, following her confirmation, Jackson mentioned with gratitude the people who had written to her since her nomination was announced, including many children. “[O]ur children are telling me that they see now, more than ever, that, here in America, anything is possible. They also tell me that I am a role model, which I take both as an opportunity and as a huge responsibility.

“[O]ur children are telling me that they see now, more than ever, that, here in America, anything is possible.”

“I am feeling up to the task, primarily because I know that I am not alone,” Jackson said. “I am standing on the shoulders of my own role models, generations of Americans who never had anything close to this kind of opportunity but who got up every day and went to work believing in the promise of America — showing others through their determination and, yes, their perseverance that good, good things can be done in this great country.”

“To be sure, I have worked hard to get to this point in my career, and I have now achieved something far beyond anything my grandparents could have possibly imagined,” Jackson said. “But no one does this on their own. The path was cleared for me so that I might rise to this occasion. And in the poetic words of Dr. Maya Angelou, I do so now while ‘bringing the gifts my ancestors gave. I am the dream and the hope of the slave.’

“So as I take on this new role, I strongly believe that this is a moment in which all Americans can take great pride,” she said. “And it is an honor, the honor of a lifetime, for me to have this chance to join the Court, to promote the rule of law at the highest level, and to do my part to carry our shared project of democracy and equal justice under law forward, into the future.”