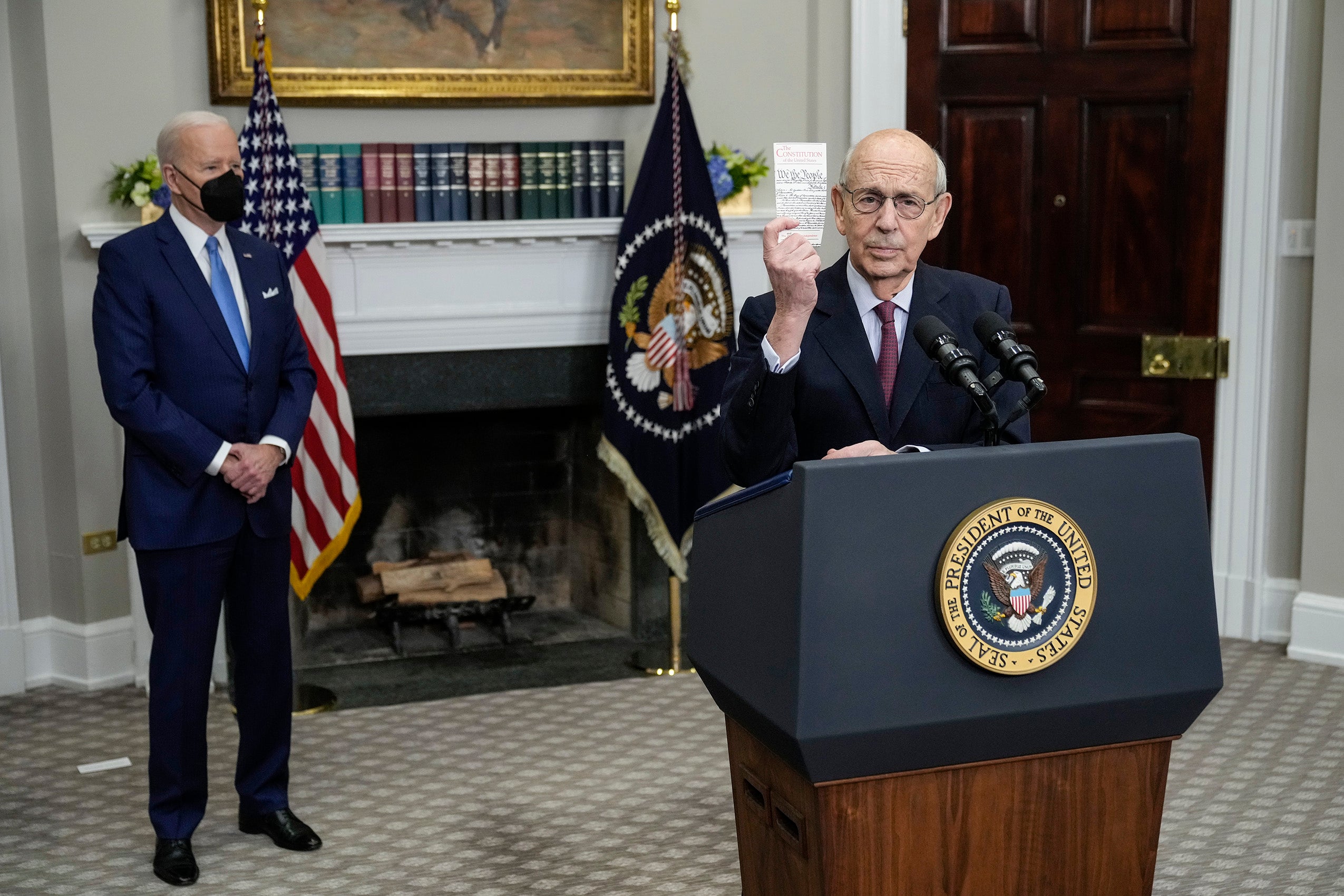

In the wake of the news that Stephen G. Breyer ’64, associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, will retire at the end of the current term, Harvard Law School faculty members – one of whom knew Breyer as a young law student – offer their thoughts on his tenure, legacy, and how the nation’s highest court could change after his departure.

Richard H. Fallon, Jr.

Story Professor of Law

Justice Breyer has distinguished himself as a moderately liberal Justice whose judicial philosophy emphasizes reasonableness, pragmatism, and civility. Although I applaud his judgment in recognizing that there is a time to go, the Court will miss both his intellectual and his personal virtues.

Charles Fried

Beneficial Professor of Law

As Yogi Berra said, predictions are always difficult, especially of the future, so I have nothing to say about whom Biden will appoint. It is rather time to reflect on the man whose announced intention to resign will precipitate a barrel full of speculation.

Stephen was my student in his and my first class at the Harvard Law School — Monday morning at 9 a.m., he as student and I as teacher. He was as clever, sophisticated and endowed with a pixieish sense of humor then as now. He has always been a close friend, in part because we have never trespassed on each other’s domains, in part because our wives have been close friends. There is one word that sums up his personality as well as his character: decency.

The public man is remarkably continuous with the private man. It has been often remarked that he never has a harsh word to say about his colleagues on the bench. But that is as true in his private conversations with good friends. It has so often happened that I would offer a critical judgment on some opinion of the Court, or on some controversial issue that the Court has decided (I never talked to him about cases before the Court or about to come to the Court), and he would explain to me the arguments on the other side, the side he disagreed with.

The genuine affection and good humor on display when he and Justice Thomas sat beside each other on the bench was just the disposition he showed in private. I recall when his uncle (“Uncle Leo”), a cranky and difficult but learned man who had lived a rather lonely life in Cambridge since his retirement, died, it was Stephen who organized a small memorial gathering in his garden, with a lovely spread put together by Joanna and a small photo of Leo on the same table. Of course I also remember the wonderful occasion when Stephen was received as a foreign member of the French Academy and he gave a charming discourse in flawless (much studied) French. He is, I believe, a Chevalier of the Legion d’Honneur. And there was the occasion on which we shared a taxi driven by a French speaking Haitian driver, and he regaled us with a recitation of the Renaissance poet Clément Marot: “Plus ne suis ce que j’ai été, Et plus ne saurais jamais l’être.”

We have reason to hope, however, that he will continue to be what he has been, and that we will profit from that.

Judge Thomas Griffith (Ret.)

Lecturer on law and former federal judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit

With Justice Breyer’s departure, the Court is losing an expert on administrative law at a time when several of the justices of the Supreme Court have called for a reexamination of that role. I hope that in the debate over his successor we will remember that Justice Breyer was adamant that judges must not be partisans in robes and in his observation that, in fact, they are not.

Vicki C. Jackson

Laurence H. Tribe Professor of Constitutional Law

When he retires, Stephen Breyer will be remembered, and missed, for his deeply thoughtful, learned, humane, and pragmatic approach on the Court. Each time I teach his dissent in the Seattle Schools case, I am struck again by his knowledge of constitutional history, his recognition of the real consequences of judicial decisions for those involved, and his appreciation of the role of democratically chosen bodies in finding ways to try to overcome the legacies of longstanding systems of racial subordination. His extrajudicial writings as a Justice have engaged with large issues, and I hope he will continue through his writing and speaking to engage with the grave challenges our country faces.

Richard J. Lazarus

Howard and Katherine Aibel Professor of Law

The best Supreme Court advocates learned to welcome Justice Breyer’s questions precisely because they were so differently pitched from those of his colleagues. Breyer’s clear purpose was to explain (at length) his current thinking about the case and then allow the advocate to respond. His goal has not been to trap the lawyer into making a concession or otherwise expose a weakness in the lawyer’s case. It has instead been to allow the lawyer to learn what Justice Breyer was thinking so the lawyer could let Breyer in turn learn if there were flaws in the Justice’s own, tentative legal analysis. In short, the questions were designed to ensure the best possible judicial decision making.