He was a baker with a high-rise dilemma.

His bakery shared a wall with a doctor’s study next door. And the machines he used to create his confections were so noisy that the doctor couldn’t use his consulting room. In short, the baker was interfering with the doctor’s ability to use his property in a manner typical for the neighborhood. The doctor sued, and won, obtaining a court order requiring the baker to stop using the machines.

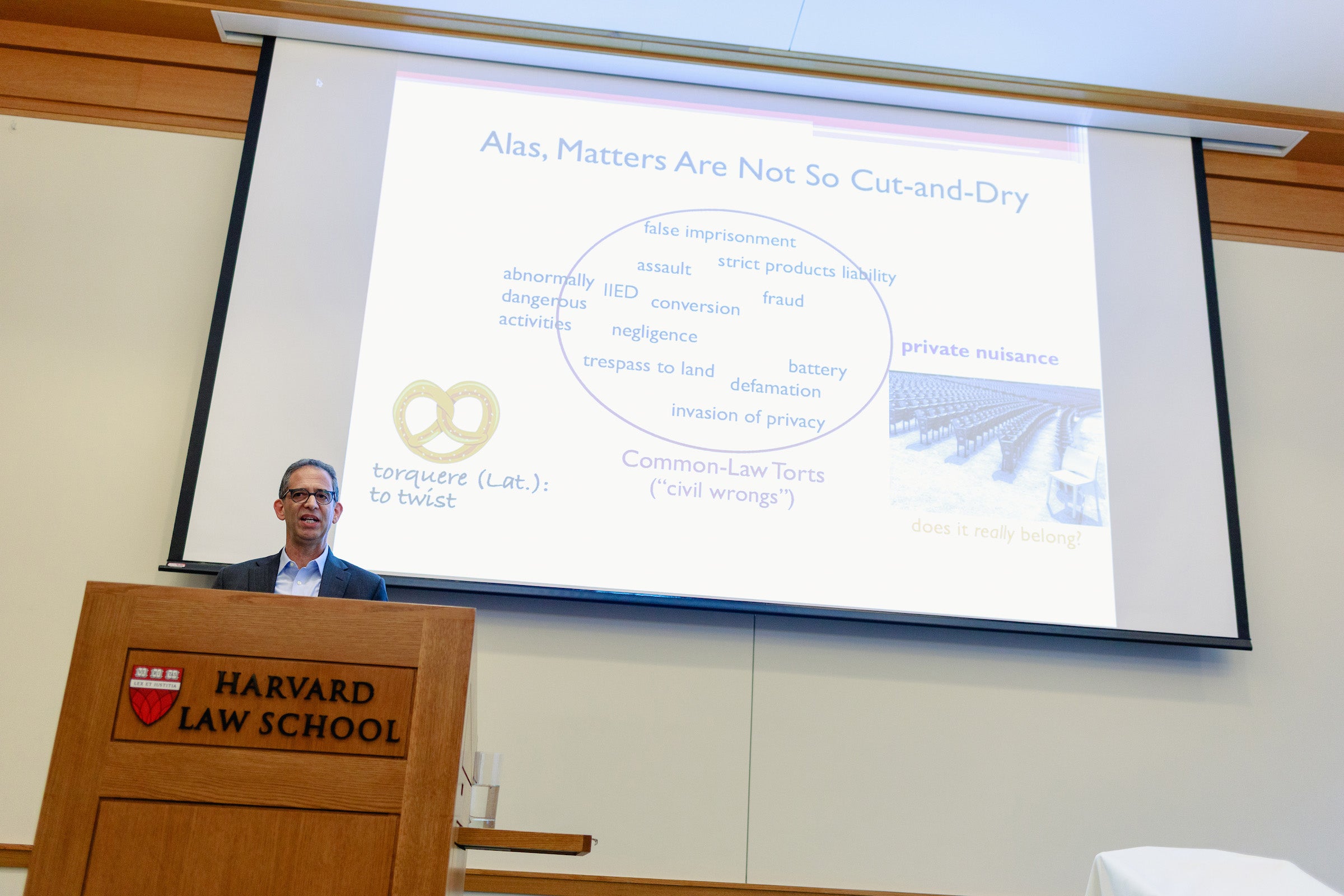

Based on the landmark 1879 case, Sturges v. Bridgman, in which, on similar facts, a British court ruled in the physician’s favor, the baker-doctor dispute cited by tort law expert John Goldberg in a recent lecture at Harvard Law School helped set the legal standard for what today constitutes the tort, or civil wrong, of private nuisance.

But, Goldberg wanted to know, what is the essence of private nuisance, and what are its boundaries? How one answers these questions, he said, could ultimately matter for the resolution of billion-dollar “public nuisance” claims against companies alleged to have fueled an array of public ills, including the opioid epidemic, gun violence, and climate change.

Goldberg’s comments came during an event celebrating his appointment as the Carter Professor of General Jurisprudence at Harvard Law School. Introducing him to a packed room of fellow faculty, students, and staff, John F. Manning ’85, the Morgan and Helen Chu Dean and Professor of Law, praised Goldberg for “his steadfast and persuasive commitment to the ideal that law has an integrity as such, that behind doctrine lies a coherent set of principles that explain it, and that it is a worthy enterprise for lawyers and those who learn and teach law to understand and apply those principles.”

Manning added that Goldberg “is a superb and award-winning scholar” and “a spectacular teacher, having taught across most of the first-year curriculum and having won multiple teaching prizes in the process.”

Tort law defines what counts as wrongfully injuring another person — assault, fraud, libel, malpractice, negligence, and private nuisance are all torts. Tort law also gives victims of such wrongs the opportunity to obtain a court-ordered remedy from the wrongdoer.

“Nuisance is yucky, as its name suggests,” Goldberg declared. “Of course, as my students know, tort [law] is yucky. Torts is a weird subject to spend your life thinking about. It’s about bad things being done to other people and it’s kind of gruesome sometimes.”

“All torts are pretzels,” he explained. “Why is that? Well, pretzels are twisted.” The word tort is derived from the Latin infinitive torquere, which means “to twist.” Like the German baked good, he explained, a tort is “twisted in multiple senses — twisted in the sense of lacking rectitude and wrongful [in the] sense of somebody gets twisted, somebody gets hurt. And it’s twisted in the sense that [the] point is to [give the victim the ability] to rectify and put things straight.”

And while the law has long considered what the baker did to the doctor a private nuisance — one among many different kinds of tort — Goldberg said that there are good reasons to ask to what extent liability for private nuisance really belongs in the category of tort. For, unlike most torts, standard formulations of private nuisance seem to lack a typical, if not essential, element of all torts: injury to another that results specifically from conduct that falls below a legal standard of acceptable behavior.

“Where’s the wrong?” Goldberg asked his audience. “If you look at a truncated definition of private nuisance, it doesn’t look like a lot of other wrongs. It doesn’t identify a way of behaving that is wrongful, exactly. It doesn’t say something like ‘A intentionally interferes with B’s use of land.’ And it doesn’t even say ‘A negligently interferes with B’s use of land.’ In fact, there’s no adverb at all in the tort. So, there’s no description of substandard conduct, which you typically see, which is why torts are typically wrong.”

Instead, he said, all that’s needed for a private nuisance — on the face of things — is conduct, right or wrong, that interferes enough with someone else’s use of their land. “So, as long as you interfere enough with somebody else’s use and enjoyment of their property, you’re subject to liability for the tort of nuisance.”

“As long as you interfere enough with somebody else’s use and enjoyment of their property, you’re subject to liability for the tort of nuisance.”

Returning to the actual 1879 case on which his hypothetical was based, Goldberg noted that the baker — actually, a confectioner — “was not a miscreant by any means” and had tried to avoid interfering with the doctor’s practice.

“The problem,” he explained, “was the baker just couldn’t operate the machines that the baker needed to operate in order to run the bakery without bothering the doctor.” Notwithstanding the baker’s efforts to muffle his machinery, the court judged the interference a private nuisance for which he was liable.

It is no accident, Goldberg explained, that Nobel prize-winning economist Ronald Coase developed his massively influential economic account of civil liability in part on the basis of nuisance cases. Picking up on the apparent lack of misconduct in cases such as Sturges, Coase argued that, instead of treating the baker as wrongdoer and doctor as victim, their interaction is better described in neutral and reciprocal terms. This and other nuisance cases merely involve an unfortunate conflict between two ordinary and acceptable activities that happen to be incompatible.

“If Coase is right about private nuisance, then we’re not looking at a tort anymore,” Goldberg said. “We’re looking at something else. We’re looking at an occasion for judges to make regulatory decisions, which is fine, but that’s a different kind of thing. It’s subject to different rules, different procedures, different values, etc.”

Responding to Coase’s approach, Goldberg argued that to establish private nuisance more firmly as a tort — which he noted is the “historical position of the courts” — legal scholars must account for how the concept interacts with private law, common law, and the idea of legal wrongs. By contrast with the regulatory perspective favored by Coase, Goldberg noted that private law defines interpersonal wrongs and enables people to obtain recourse from wrongdoers. Common law, he said, “is all about translating social and moral norms into legal rules.” A legal wrong, he explained, is a violation of a legal directive that is designed to guide a person’s conduct.

The baker, Goldberg argued, had violated the common law “norm of neighborliness.”

“I think it is unneighborly to constantly make noise with your bakery to drive your neighbor doctor crazy, right?” he said. “And it doesn’t mean you’re careless; we’re not talking about negligence. It doesn’t mean you intended to drive the doctor crazy or anything like that. It’s just not a way in which neighbors should interact with their neighbors. It’s taking too much liberty for yourself and not being sufficiently attentive to the … interests of your neighbors.”

This analysis led Goldberg to ask what he termed the “$64,000 question.” That question is this: “Is there a coherent and useful general common law concept of nuisance?”

While most of his lecture concerned private nuisance, Goldberg noted that it rubs up against another legal concept, that of public nuisance. Historically, public nuisances were low-level crimes that, while in the first instance an offense against the public rather than any one individual, could sometimes give rise to tort liability.

To explain this idea, he offered the example of someone who builds a structure that blocks a public road, making it unusable by all members of the public. The person or entity that creates the blockage commits the offense of public nuisance. But then, if a driver were injured because of the blockage, the driver would have a tort claim for damages. In this and other cases, “the crime of public nuisance, where applicable, generates potentially civil liability.”

Why is this the $64,000 question? Because, Goldberg said, much of “today’s biggest litigation is all about public nuisance.” And billions of dollars, not tens of thousands, are on the line.

Goldberg pointed to several areas in which lawsuits have been filed by individuals and organizations that seek to impose liability for alleged public nuisance violations. “Plaintiffs lawyers around the country are bringing lawsuits” on behalf of people as well as cities and states claiming harms and seeking redress from public nuisances, he said, citing recent litigation against companies that make and sell opioids as one among several examples.

Their argument, according to Goldberg, is that the fallout from the opioid epidemic counts as a public nuisance. In other words, governments and individuals facing the dire consequences of the epidemic are claiming to be like the car victim who’s hurt by the blockage in the road, and hence that they should be able to recover damages from various entities, including manufacturers, on a public nuisance theory.

A key question in the resolution of this litigation, Goldberg said, will be how to understand the connection, if any, between private nuisance and public nuisance. While many legal scholars have argued that the two have only a nominal or superficial connection, Goldberg speculated that public nuisance and private nuisance have closer historical and conceptual links. If this turns out to be the case, he concluded, this should inform courts’ judgments about when there should be liability for public nuisance.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.