As a war crimes investigator during World War II, Benjamin Ferencz ’43 was among the first outside witnesses to document the atrocities of Nazi labor and concentration camps. In an account of his life, he wrote that he was “indelibly traumatized” by the scenes he’d encountered. “My mind would not accept what my eyes saw. … I had peered into hell.”

Internationally renowned for his role as chief prosecutor in the Nuremberg trials, and for championing the creation of the International Criminal Court, Ferencz dedicated his career to promoting international rule of law to protect the most fundamental rights of human beings everywhere. In an oral history, Ferencz said he felt he owed it to the memory of those who perished in the camps to continue to try to build a more peaceful and humane world, and to never give up hope.

Ferencz died on April 7. He was 103.

“Ben Ferencz devoted his life to building a more humane world and, in the process, inspired generations of lawyers and left an indelible legacy,” said Harvard Law School Dean John F. Manning ’85. “We owe him a deep debt of gratitude for the historic work he did at Nuremberg and beyond.”

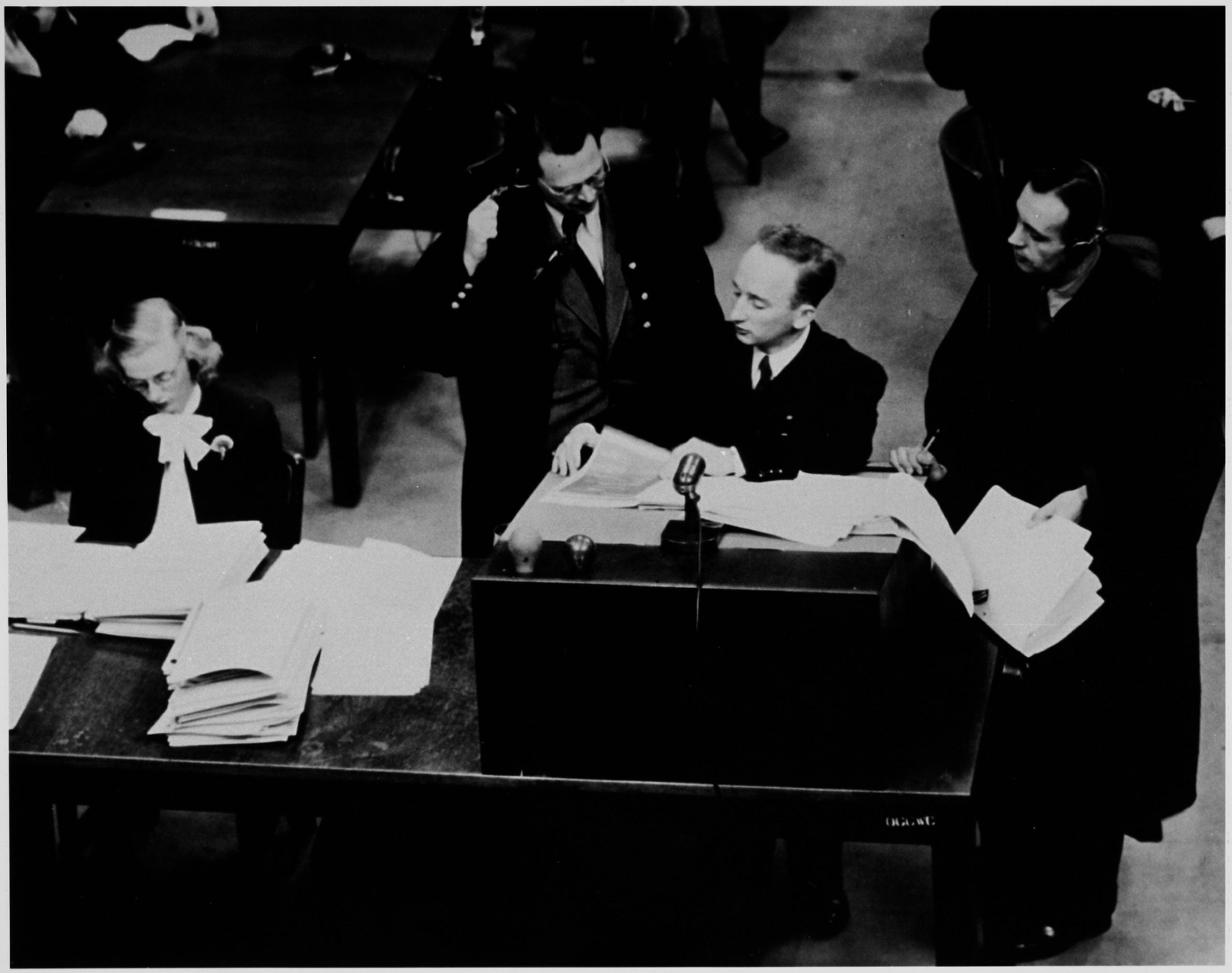

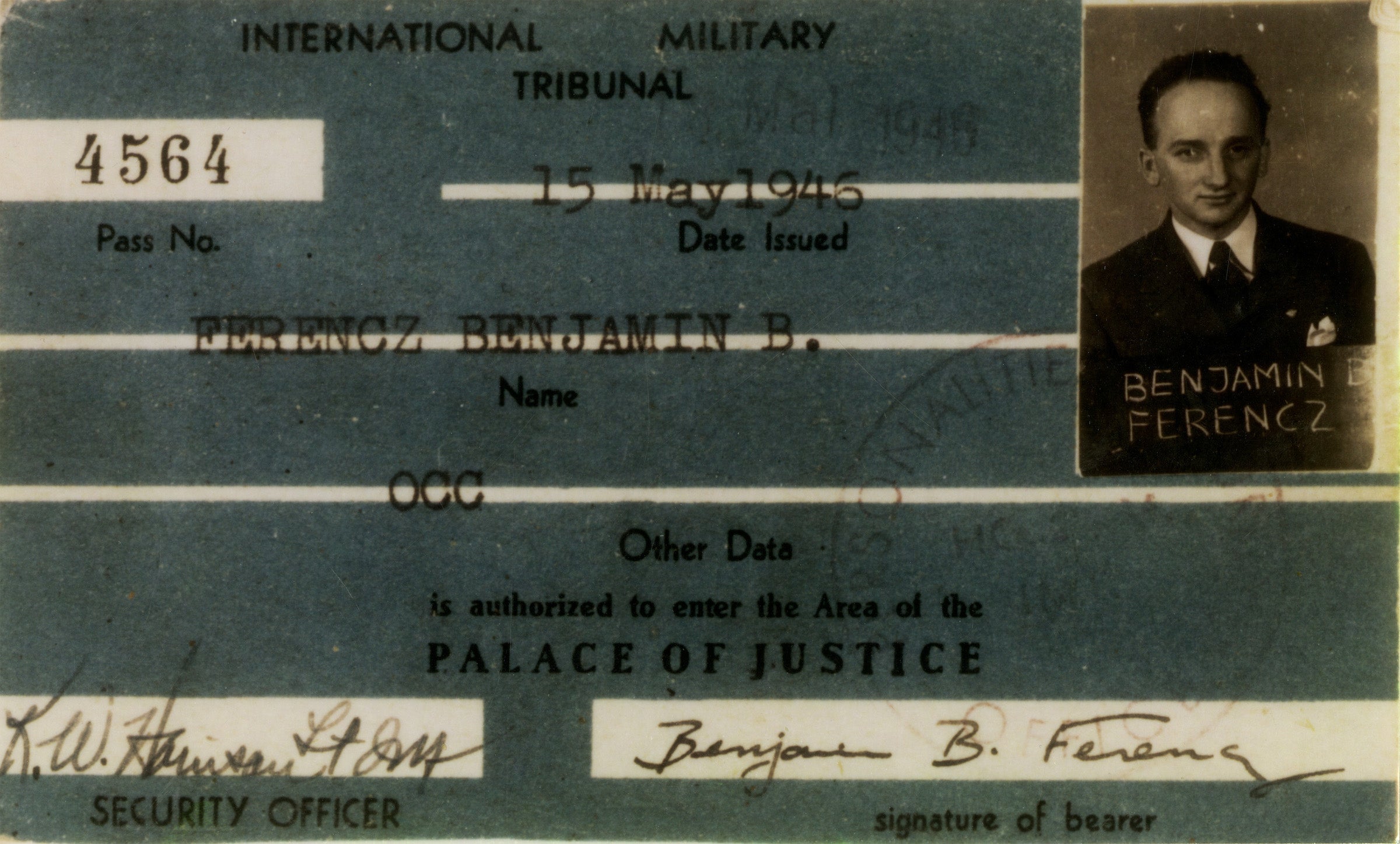

In 1947, four years after graduating from Harvard Law School, Ferencz began serving as chief prosecutor for the United States in the Einsatzgruppen case at the Nuremberg Tribunal, in which 22 Nazi officials, including six generals, were charged with murdering more than 1 million people. It was considered the largest murder trial in history, and all the defendants were convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Thirteen were sentenced to death, and four were ultimately executed. It was Ferencz’s first case as a lawyer.

In a 2018 interview, Ferencz said: “My problem as the prosecutor was to ask, ‘What do I ask for? Do I ask to sentence them all to death?’ Twenty-two defendants against a million people murdered? I said there’s no way of balancing enough — of doing justice there. But if I could get them to create a more humane world, using this as an example, that would be worthwhile.”

He asked the court to affirm by international law the right of all people “to live in peace and dignity regardless of their race or creed.” Today, the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg is widely regarded as having changed the course of history. During the trials, the concept of crimes against humanity began to emerge, and the groundwork was laid for the Genocide Convention.

Ferencz spent the next decade in Germany, where he coordinated reparations claims and directed restitution programs for Nazi victims.

“It had never happened in human history that the defeated nation was offering to pay compensation to the individual survivors of a war of aggression,” Ferencz said. “It was the enactment of something I learned in my first year of the Harvard Law School: If you harm somebody illegally, you have an obligation to try to make amends. The ability to see that in practice, to help put it into practice, I’m kind of proud about that.”

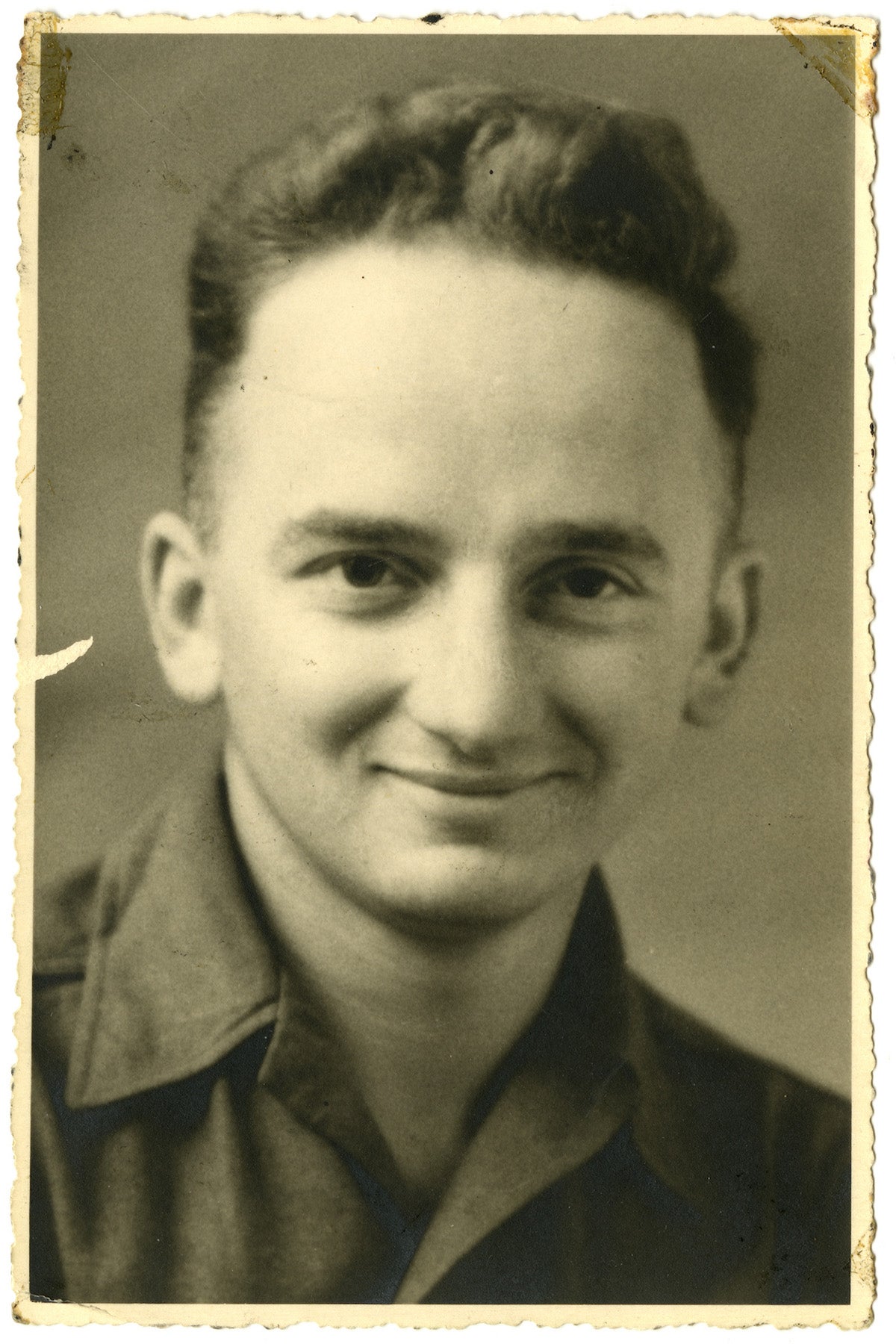

Born in the Transylvanian village of Somcuta Mare, Romania, in 1920, Ferencz emigrated with his family after World War I, landing in the Hell’s Kitchen district of New York. Surrounded by crime and mired in poverty, the family lived in the cellar of a tenement house where Ferencz’s father worked as a janitor.

Ferencz didn’t attend school until he was 8 years old because, he said, he spoke only Yiddish. By eighth grade, he was recognized for his intellectual aptitude and was sent to a preparatory school for gifted boys, which earned him automatic admission to City College of New York.

Intending to pursue a career in criminal law and juvenile justice, Ferencz enrolled at Harvard Law School in 1940 and sought out a research position with Sheldon Glueck, a leading criminologist who taught at the school. Glueck, who was considering writing a book on German aggression and atrocities, instructed Ferencz to summarize every book in the Harvard library that related to war crimes. It was an assignment, Ferencz said, that “probably changed the course of my life.”

Ferencz enlisted in the U.S. Army after graduation, serving for nearly three years in an artillery battalion and earning five battle stars. In 1945, at what he suspects was Glueck’s recommendation, he was transferred to the Judge Advocate Section of Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army headquarters, where he was assigned to the newly created War Crimes Branch to collect and investigate evidence of Nazi brutality.

After the war, he briefly returned to New York, and a chance encounter with a law school classmate resulted in an invitation to interview for a forthcoming war crimes trial in Germany.

In addition to prosecuting the Einsatzgruppen case at Nuremberg, Ferencz also served as special counsel prosecuting the Krupp trial, one of three proceedings against German industrialists whose directors were accused of crimes against humanity and of exploiting 100,000 laborers. Eleven directors were found guilty and served prison time.

With Nuremberg chief counsel Telford Taylor ’32, Ferencz co-wrote “Less Than Slaves,” a book that describes the quest to persuade German industrial firms to compensate concentration camp victims who were exploited as forced laborers.

For 13 years, Ferencz worked in private practice. Around the time of the Vietnam War, he decided to direct his time and energy as a law teacher, writer, lecturer, and lobbyist advocating for world peace and an international legal system.

He published several books — including “Defining International Aggression: The Search for World Peace” (1975), “An International Criminal Court: A Step Toward World Peace” (1980), “Enforcing International Law: A Way to World Peace” (1983), and “PlanetHood” (1988) — and he also campaigned relentlessly for the establishment of a permanent court to try the world’s most serious crimes and for laws establishing the crime of aggression.

In the late 1990s, he began to see his dream come to fruition when the international community began debating the creation of an International Criminal Court.

In 2011, at the age of 91, Ferencz delivered the closing prosecution speech at the first trial ever heard before the International Criminal Court in The Hague — of the Congolese warlord Thomas Lubanga Dyilo. Repeating a statement from his opening remarks at the Einsatzgruppen trial more than 60 years before, Ferencz said, “The case we present is a plea of humanity to law.”

He added, “The hope of humankind is that compassion and compromise may replace the cruel and senseless violence of armed conflicts.”

Hope guided Ferencz’s long life and remains his lasting legacy.

When asked for a personal anecdote from his time investigating the camps, he told this story.

His standard procedure was to immediately secure camp records. On entering one camp, he was approached by a French inmate who told him, “I’ve been waiting for you.” Leading Ferencz to an area near the electrified fence, the man dug a deep hole and unearthed hundreds of SS identity cards wrapped in rags. The cards indicated membership to a social club in the camp. Instead of destroying the documents, the inmate, at great danger to his life, had secretly buried them, believing one day there would be liberation.

“I was struck by the fact that there’s a man who faced death every day, who had to face the mass murderers, and he risks his life a hundred times over to save these cards because he has faith that one day justice will be done,” said Ferencz.