Eli Rosenbaum ’80 sticks a tape in the VCR in his office. An elderly man, tanned and silver-haired, speaks in German before a microphone. It’s Günther Tabbert, an SS officer during World War II, who helped direct the execution of all the Jews of Daugavpils, Latvia –more than 1,000 men, women, and children. Here he is, more than 50 years later, when he was stopped at John F. Kennedy Airport as he tried to enter the United States. Rosenbaum translates: “I can’t believe anybody cares about those events of so long ago.”

Eli Rosenbaum cares. Although he was born 10 years after the Third Reich was defeated, he’s made it his life’s work to seek a measure of justice for its victims by pursuing the Holocaust’s perpetrators. Rosenbaum heads the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Special Investigations (OSI), whose primary mission is to track down Nazi war criminals living in this country, denaturalize, and deport them (the United States has no jurisdiction to try them for World War II crimes).

OSI was created in 1979–decades after Cold War politics and U.S. immigration policy made it easier for Nazis to enter the United States in the first place. When OSI does succeed in denaturalizing Nazis, few foreign countries will try them. And the reality that makes some question the continuing existence of OSI contributes to Rosenbaum’s sense of urgency; those complicit in the genocide that exterminated 11 million people–6 million of them Jews–are either dead or very old. With every delay, another one could die peacefully in his bed on American soil.

* * *

One day, when Rosenbaum was a teenager, during a long road trip, his father told him he’d been sent into Dachau concentration camp a few days after it was liberated. A former Army intelligence officer, Rosenbaum’s father had told his son plenty of World War II stories, but not this. When Rosenbaum asked him what he’d seen there, his father didn’t speak. And Rosenbaum says he never asked again: “His silence and his tears told me everything I needed to know.” Rosenbaum has since become all too familiar with the details.

* * *

As a law student, Rosenbaum read a book by journalist Howard Blum about the search for Nazis in America. He remembers how angry he was to learn “that people who had committed genocide had come to the United States, and that our government wasn’t doing anything about it.”

When he stumbled upon a notice in the paper announcing the opening of a unit at the Department of Justice to look into suspected Nazi war criminals living in the United States, he called immediately and convinced the director of OSI to take him on as its first summer intern. Rosenbaum already had an M.B.A. from the Wharton School and had planned on a career in corporate law or the business world, but after that summer he knew he wanted to go back to OSI.

The next year he wrote his third-year paper on the prosecution of Nazi war criminals and the Holtzman Amendment, the legislation thathe’s now spent his career enforcing. Former congresswoman Elizabeth Holtzman ’65, a driving force behind the establishment of OSI, authored the statute, which was passed in 1978. It makes those complicit in atrocities committed during World War II subject to denaturalization, closing loopholes in immigration law that had allowed them to enter the United States.

When Rosenbaum noticed that the statute of limitations on prosecuting Nazi war crimes in Germany was about to expire, he led the school’s Jewish Law Students Association in a campaign to gather signatures of protest from law professors around the country. He also convinced Helmut Schmidt, chancellor of West Germany, who was speaking at Harvard’s commencement that year, to meet with him. And, although Rosenbaum won’t take any credit for it, he was relieved when the German Parliament did eventually extend the statute of limitations indefinitely.

* * *

Rosenbaum learned early on how things can be hidden in plain sight. As a 3L he read an account of slave labor at an underground V-2 missile factory at the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp. He then realized from other reading that Arthur Rudolph, a rocket engineer who’d directed production at the plant, had come to the United States along with other German and Austrian scientists. At NASA Rudolph had gone on to manage the Saturn 5 rocket project and the Pershing missile program.

After graduation Rosenbaum began as a trial lawyer at OSI. And although he took on other investigations, he didn’t forget Rudolph. Eventually OSI found records in the National Archives that Rosenbaum believed confirmed Rudolph’s link to the persecution of forced laborers. Among other details, he learned that Rudolph had attended a mass hanging and had required other inmates to observe the slow strangulation of fellow prisoners who were accused of plotting rebellion.

Rosenbaum confronted the retired scientist during an OSI interview. Eventually he agreed to renounce his U.S. citizenship and left the country for Germany.

It’s not that Rosenbaum thinks the U.S. government’s choice was a simple one. He speaks with admiration of the space program. He believes that after the war there was an urgent security need for missile technology. But someone should have recognized that “there was a moral price to be paid in using people who were implicated in Nazi crimes.” And if these people were rescued “from a destroyed Germany and [allowed] to live in great comfort in the United States and to work in the field that they cared so much about, there should have been a time when we said: Rather than retire here, go back to Germany.”

Rosenbaum was gratified to see Rudolph go. “The survivors who’ve made new homes here ought not to run into their former tormentors in the Safeway,” he says. Yet Rudolph, like so many people OSI has prosecuted, was never tried in his home country, and that, Rosenbaum says, is one of the great frustrations of his work: “We have spent countless hours over the years pressing governments in Europe to do the right thing. We’ve had limited success.”

One of the rewards is setting the record straight. And when it comes to World War II, that’s what OSI knows how to do. The unit now includes 13 attorneys but also 10 historians, versed in many languages, who track down evidence in archives in the United States and abroad on crimes committed more than a half century ago. “Together,” Rosenbaum says, “we assemble these enormously intricate evidentiary jigsaw puzzles.” The archival research also feeds a “watch-list” of former Nazi and Axis war criminals to be excluded from the United States. Some 70,000 names are on the list. OSI gets a call at least once a month from airports around the country. Since 1989, when records started to be kept, 165 people have been turned away (including Günther Tabbert).

Just as OSI cases were beginning to drop off in the ’80s (“the biological solution” at work, says Rosenbaum), the fall of Communism provided an infusion of new evidence. Researchers were allowed into archives, whose documents had previously been available only at the discretion of Soviet intermediaries. OSI was suddenly able to develop new cases and revive old ones that had reached dead ends.

Rosenbaum was working on one such case in 1983. Aleksandras Lileikis had been chief of the Lithuanian Security Police in Vilnius province during Nazi occupation. Since the ’50s he’d been living in Massachusetts. Only 5,000 of Vilnius’ 60,000 Jews survived the war. Thousands were sent to Paneriai, a wooded hamlet outside of Vilnius, where they were stripped of their clothing, lined up in pits, and shot. Rosenbaum was eager to bring to justice a man believed to have ordered such atrocities and who, unlike many of the men OSI prosecutes, was not simply “a trigger puller.” Rosenbaum confronted the 76-year-old in his home with a document that consigned 52 Jews to the killing squads in Paneriai. Although Lileikis’ name was typed at the bottom of the page, the order was not signed, and Lileikis denied any knowledge of it. Rosenbaum remembers Lileikis’ challenge: “Show me something I signed.” Despite requests for documentation from the Soviet Union, nothing turned up, and the case that Rosenbaum wanted so badly to move forward lay dormant.

Ten years later, in 1993, OSI’s senior investigative historian had gotten access to Lithuanian archives. As he sorted through records from the Lukiskes prison in Vilnius, he found what they’d been hoping for: order after order–sending Jews to prison, sending them to labor camps, handing them over to the killing squads–all signed by Aleksandras Lileikis. By that time Rosenbaum had become principal deputy director of OSI, and it was David Mackey ’83, head of the civil division of the U.S. Attorney’s Office, and OSI attorney William Kenety ’75 who filed the case. They won on summary judgment; Lileikis was stripped of his citizenship and left the country rather than face deportation charges. He was put on trial in Lithuania for genocide, but the prosecution was never completed, ostensibly due to the poor state of Lileikis’ health, says Rosenbaum.

Among those Lileikis sent to their deaths was a 6-year-old girl, Fruma Kaplan, and her mother, Gita. Rosenbaum flips through a notebook in his office to copies of identification papers of men and women held in the Lukiskes prison. Faces stare back: Alta Knop, Irsas Levinas, Esther Sandleryte, but no Fruma. Rosenbaum and his team have tried to find out more about her–obtain a photograph, learn the whereabouts of the Lithuanians who tried to shelter the girl and her mother from the Nazis. But there’s only the paper trail of her travels from prison to execution pit. Rosenbaum remembers a lullaby sung to children in the Jewish ghetto in Vilnius: All roads lead to Paneriai, but no roads lead back.

* * *

For a man who thrives on moral outrage and black coffee, Rosenbaum is not afraid of sounding corny. Although he loved being a trial lawyer, he thinks the biggest thrill in his career was not the cases he tried or the cases he won, but the moment he appeared as an attorney for the Department of Justice for the first time and said, “May it please the court, my name is Eli Rosenbaum, and I represent the United States.”

“For a lawyer,” he says, “I don’t think there is a greater honor.”

He will also tell you that, besides being a father, nothing else in his life has had as much meaning as this work–despite the frustrations that sometimes seem as numerous as the names on the watch-list.

When summer interns at OSI ask him for career advice, this advocate for public service counsels them to consider a stint in the private sector. How else will they know if they’ve made the right choice? Back in 1984, when the frustrations got to him, he went about answering that question for himself by leaving OSI and taking a job as a corporate litigator at a large firm in New York. He found he missed the challenge and responsibility he’d been able to take on so quickly after law school. And although he wanted to do his best for the firm’s clients, in his heart he “didn’t care which of the corporate monoliths won.” Above all, Rosenbaum missed caring.

Within a year he became general counsel of the World Jewish Congress and led an investigation of the Nazi past of former UN secretary general Kurt Waldheim, who at the time was running for president of Austria. Rosenbaum’s account of the cover-up and its investigation, Betrayal (St. Martin’s Press, 1993), written with William Hoffer, stirred up controversy, and not just among supporters of Waldheim. Rosenbaum found himself confronting one of his childhood heroes, Nazi hunter and Holocaust survivor Simon Wiesenthal. During his investigation, Rosenbaum discovered and disclosed that Wiesenthal had previously been presented with evidence of Waldheim’s past, yet he continued to defend him even as the details of Rosenbaum’s investigation were released.

Professor Alan Dershowitz says Rosenbaum was courageous to take on an icon like Simon Wiesenthal. Rosenbaum was a student in Dershowitz’s professional responsibility course and attributes his decision to work at OSI at least in part to Dershowitz’s encouragement.

In 1988 Rosenbaum returned to OSI as principal deputy director at Director Neal Sher’s request. In 1995, when Sher left, Rosenbaum was appointed director. He has now worked at OSI for 17 years and is the longest-serving investigator and prosecutor of Nazis in the country and perhaps the world. “He’s somebody who has really devoted his life to trying to achieve justice in an area where very few care about justice,” says Dershowitz. “The world wanted very much to move on beyond the Holocaust. . . .

“He’s the kind of guy that Harvard should be proud of. All of our students, when they come here, write essays about how they are going to do public interest work, and then they end up going out and just making money. Eli is a guy who kept the promise.”

* * *

Rosenbaum has participated in special projects at OSI over the years, from a report on the United States’ role in helping Klaus Barbie, the Gestapo chief of Lyon, elude French justice, to tracing the whereabouts of Josef Mengele. At one point, a sample of Mengele’s remains spent a few days in Rosenbaum’s desk drawer, “an appropriate posthumous humiliation,” he says.

Yet the project for which Rosenbaum may have received the highest accolades is not necessarily the one that gave him the most satisfaction. In 1997 his office provided key detective work in an interagency investigation into looted Nazi gold and other stolen assets.

Stuart Eizenstat ’67, who spearheaded the efforts as undersecretary of state for economic, business, and agricultural affairs, explains that when a report was first prepared, “We had great difficulty in determining whether any of the gold pool collected by the Allies had been from victims, as opposed to the central banks of the countries the Nazis occupied.” This was not merely academic, says Eizenstat. After 60 years, six tons of gold still had never been distributed. “We were very close to issuing the report, and Eli insisted that we should not publish it until we pursued this further and that he would not sign off for the Justice Department until we did.”

Concerned that the final report would not be complete, Rosenbaum pulled his staff off of other work to focus on the project. Within weeks, he and OSI historians were able to trace shipments of victim gold to European countries, including Switzerland (one of Germany’s major sources of foreign credit and equipment during the war). OSI’s discoveries made it into the report, and largely because they did, Eizenstat eventually was able to convince most European countries involved to donate the value of their part of the six tons of gold to a Nazi persecutee relief fund.

Eizenstat acknowledges that Rosenbaum’s tenacity may have rubbed some people the wrong way: “He sent some very tough letters to people about the quality of their work.” But Eizenstat says, “It’s important to understand that his passion was supported by facts. He didn’t ask that we put things in simply as an emotional response–only when he could find the evidence.”

Rosenbaum and his team received a Justice Department award for their contribution. He says he is glad that his office participated in the “pursuit of historical justice,” but the high level of interest in the issue of looted gold and artwork clearly grates on him. He believes it is a question of skewed priorities. “These are crimes of property. The typical victim of the Holocaust was middle class or poor. What they had were their lives,” he says. “A third of all Jews who were alive on earth before the war were murdered.”

* * *

In February John Demjanjuk was stripped of his citizenship for the second time, when Chief Judge Paul Matia ’62 ruled that OSI evidence showed he’d been a guard at several forced-labor camps and the Sobibor death camp. Rosenbaum is proud of the litigation victory and of his team’s performance in a tough case. But he looks weary when asked about the history of Demjanjuk’s prosecution, which goes back some 25 years, to before the office was created. Although Demjanjuk was extradited to Israel in 1986 and then sentenced to death based on survivor evidence that he was the Treblinka death camp guard known as Ivan the Terrible, documents emerged suggesting that he was the wrong man. Demjanjuk’s conviction was overturned, his citizenship was reinstated, and OSI came under fire. In 1999, under Rosenbaum’s leadership, the office brought new charges based on evidence that Demjanjuk was a guard at other camps, including Sobibor. After the judge’s ruling in February, the octogenarian could be deported again, but only after all appeals are exhausted and only if the government can find a country that is willing to take him.

To date, 67 Nazi war criminals and collaborators have been denaturalized and 54 have been permanently removed from the United States. Eighteen cases are presently in litigation and more than 170 persons are currently under active investigation. According to the latest Simon Wiesenthal Center report on activity in Nazi war crimes cases, the United States’ success by far surpasses that of other countries. So far only eight people deported from the United States for complicity in Nazi crimes have been tried abroad on criminal charges, and only three have been convicted.

“The whole process of bringing war criminals to trial is very much imperfect justice,” says Dershowitz. “But imperfect justice is a lot better than perfect injustice.” More important than the numbers, he says, “is the fact that the United States government has made a commitment to the world that it will take seriously these issues, and it has led the world in this regard.”

OSI continues to take on cases and to uncover documents. Recently one of the researchers found a planning document for “the resettlement” of Jews–the proposed location, “two pits.” “Your heart just drops when you see that,” says Rosenbaum, “but it inspires you.”

Rosenbaum says he’s not sure what other work he could have done where he would have met so many heroes–Nuremberg prosecutors and Nobel Prize winners among them. But he seems equally honored to have shaken hands with the unsung heroes: survivors who have trusted him enough to tell their stories, providing evidence, even when talking about the past reopened painful wounds. Rosenbaum says he thinks often about a man who participated in “one of the great escapes of history” from the Sobibor death camp, survived the rest of the war in occupied Poland, but today still wrestles with how the Nazis could have wanted to kill his mother.

Although, according to Rosenbaum, OSI has enough cases for several years of work, the office’s life span dwindles as the suspects get older and frailer.

Holtzman, the former congresswoman who also served as a district attorney, believes that as long as the perpetrators can understand the charges against them, “every Nazi war criminal in this country should be brought to justice.

“I don’t see how we can walk away from the Holocaust without sending a terrible signal to the murderers of today, the people who still want to kill civilians, and who torture other human beings, who want to wipe out ethnic groups.”

In 1999 the Senate passed a bill that would extend OSI’s role to include investigating other torture and genocide cases, but it never got through the House. “It should be the attorney general’s decision,” Rosenbaum says. “But if we are called upon, we’re ready.”

When the office dissolves, Rosenbaum says it will organize its declassified records for public scrutiny, so “what can be disclosed is disclosed.” So many documents have been discovered and translated over the years, many from classified archives. He likes to think this will lead to “at least a small renaissance” in the study of Nazi crime.

* * *

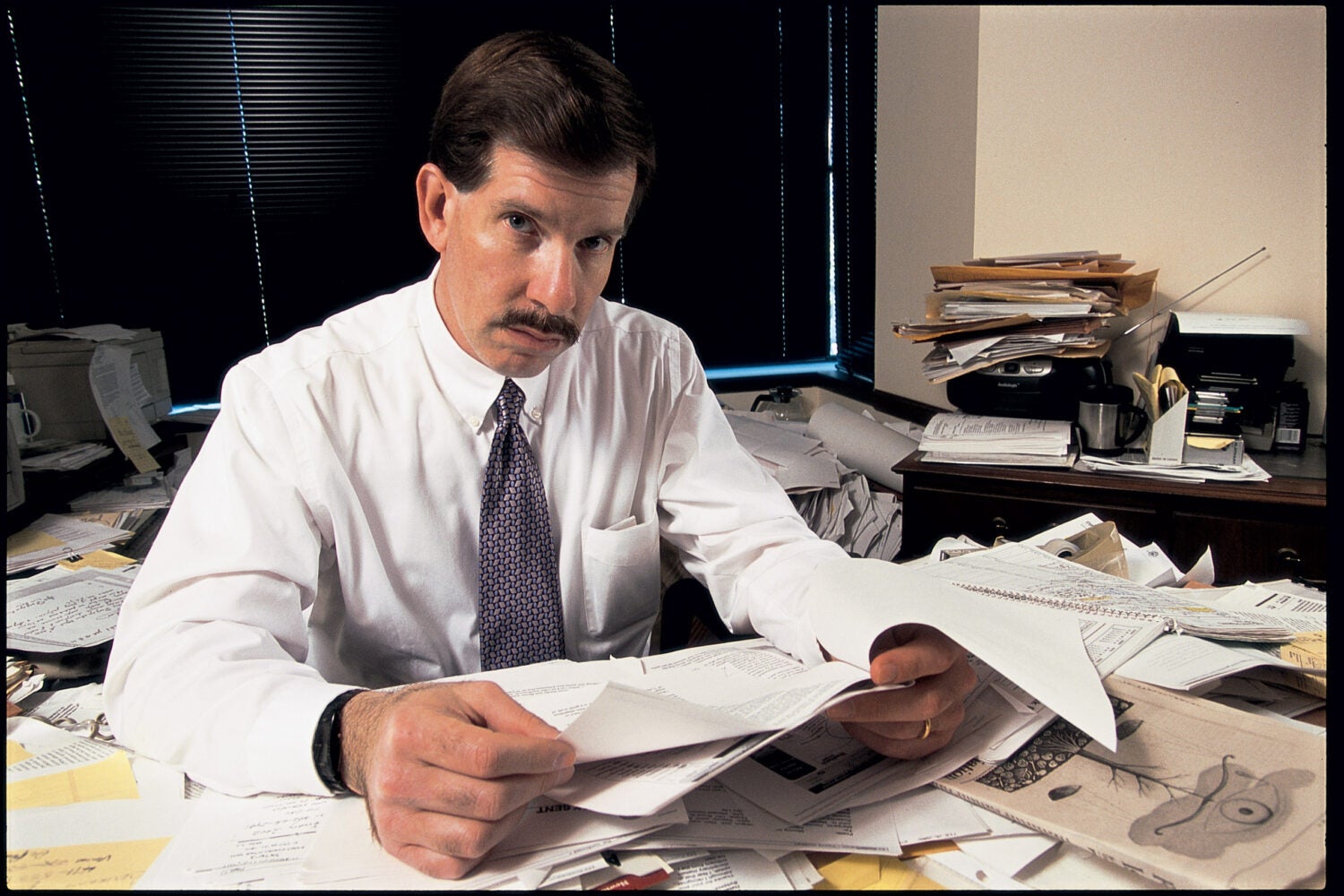

On his way to and from the office, Rosenbaum listens to recordings of radio stations from the ’60s and ’70s–snatches of news, music, weather from ordinary days some 30 years ago. He’s collected over a thousand of them. During his drive he listens and takes a little time from a job that has absorbed much of his life, so many weekends and evenings that he could have spent with his wife and daughters. He’s received many commendations over the years, from the Justice Department, from survivors groups. An award from University of Pennsylvania Law School cites personal sacrifices and dangers faced. He says the dangers, in fact, are no greater than those most prosecutors encounter (unless you consider the fattening meals served to him in survivors’ kitchens). But the pace of the work has not let up. Files and papers cover every surface in his office, record after record of atrocities to be vindicated while there’s still time. Rosenbaum won’t tell you he hasn’t thought about how his life could be more leisurely by now if he’d pursued the corporate path that brought him to law school in the first place. The job takes its toll on you, he says. There’s foreign governments’ reluctance to assist, their indifference to prosecution. There’s the frustration of dealing with other U.S. government agencies. There’s learning of so much suffering that he can’t undo. He says he knows he owes the survivors the truth; they’ve been lied to so often. And telling the truth is enough to get him beyond the frustrations most days. But he also allows himself those moments in the car, as if the recordings could take him back to a time when he didn’t know what he knows now.