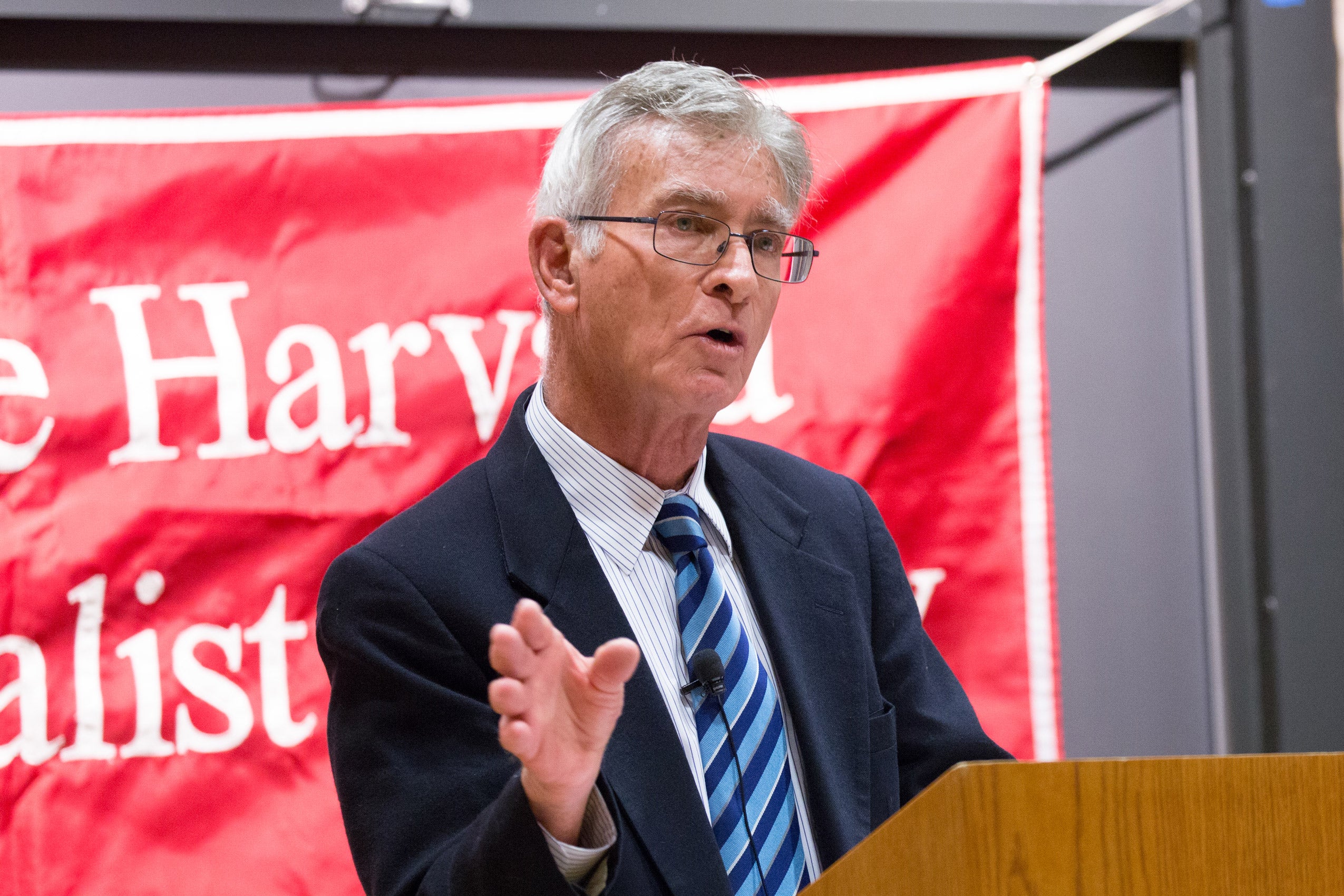

Lawrence Alexander, the Warren Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of San Diego School of Law and the author of “Demystifying Political Reasoning” and “Crime and Culpability,” delivered a talk titled “Law and Politics: What is their relation?,” as part the Herbert W. Vaughan Academic Panel on March 24. The event was co-sponsored by the HLS Federalist Society.

Following Alexander’s remarks, Professor Mary Ann Glendon moderated a panel discussion with James Stoner, a professor and director of the Eric Voegelin Institute in the Department of Political Science at Louisiana State University, and Dr. Matthew Franck, director of William E. and Carol G. Simon Center on Religion and the Constitution at The Witherspoon Institute, on the relationship between law and politics.

Following Lawrence Alexander’s talk, Professor Mary Ann Glendon (right) moderated a panel discussion featuring (from left) Alexander, Dr. James Stoner (professor and director of the Eric Voegelin Institute in the Department of Political Science at Louisiana State University), and Dr. Matthew Franck (director of William E. and Carol G. Simon Center on Religion and the Constitution at The Witherspoon Institute).

Harvard Law School Dean Martha Minow introduced Alexander, saying “There is no one I’d rather hear from on this subject.” Minow noted that the Vaughan Panel is a biennial event endowed by the late Herbert Vaughan SB ’41 LLB ’48, to promote and advance understanding of the founding principles and core doctrines of American constitutionalism. She said: “I love the panel process because it leads to a great and vibrant discussion.”

Professor Mary Ann Glendon welcomed Lawrence Alexander to Harvard Law School for the Herbert W. Vaughan Lecture Series and Panel Discussion, which is held biennially at the law school.

The most important aspect of the relationship between law and politics, Alexander said, is what he often refers to as “the gap.” It is “the single most important and revealing prism through which to view legal phenomenon.”

The gap, Alexander explained, “is the difference between what rational legislators’ first order reasoning tells them they should require you to do, and what your first order of reasoning tells you you should do.” The dilemma is that politics tells us to follow rules our practical reasoning tells us not to.

The gap can explain the fact that some judges prefer rules and some prefer standards. In his own anecdotal research as a panelist at both an east coast and a west coast conference of Federal bankruptcy judges, he found the judges divided on each side of the gap. In three particular vignettes presented to the conference audience, in which the application of the rules would seem particularly unfair, he asked if the judges would follow the rules or depart from them. “Interestingly, in both conferences, approximately half the judges said they would follow the rules, and half said they would not.”

The gap can also explain legal doctrine over time. “When standards prevail, there is a movement to translate them into rules, but when rules prevail, there is a movement to wipe them away in favor of standards. There is a grass-is-always-greener phenomenon, because we want both the virtues of rules and the virtues of standards, and we cannot have them simultaneously.”

When bureaucrats act under vague standards, Alexander said, “we feel … totally at sea, and we want to know what the rules are, but when they act under rules and make no exceptions, they become caricatures in our eyes — soulless rule-following. We want clear rules, except when we don’t.”

“There is, I believe, no way to eliminate this gap,” he said. “The problem is we are not omniscient gods. Omniscient gods can live by standards alone.”

What Alexander calls “The Spike Lee Law” or “The Queen of Standards” — do the right thing — would be the only law omniscient gods need. “We who are not omniscient gods need rules.”

Alexander then reviewed various strategies to narrow the gap — all of which he viewed as failing — including presumptive positivism, which “tells us to put a thumb on the scales in favor of what the rules prescribe. This narrows but does not close the gap.”

“If we equate first order practical reasoning with politics, and equate rules with law, while politics says we should have law, politics simultaneously tells us we cannot have it.”

“I equate law with rules that settle determinately what must be done. And I equate politics with first order practical reasoning—the reasoning that produces the rules, and the reasoning that standards abide to. Politics leads to law, but politics then conflicts with it. The question for me is, if law is desirable, as I believe it is, is it nonetheless possible, and if so, how?”

The Vaughan lecture is given every other academic year. In years when the Vaughan Lecture is not given, the Fund will support academic activities sponsored or co-sponsored by Harvard’s Federalist Society Student Chapter for the same topics addressed in the Lectures. These may, among others, include federalism, executive leadership, judicial independence and power, religion in American public life, and other matters related to the Constitution of the United States and its implementation in American life. Supreme Court Associate Justice Antonin Scalia ’60 delivered the inaugural Vaughan lecture in 2008.