When Randall Kennedy, the Michael R. Klein Professor of Law at Harvard, was a boy, his father, Henry Kennedy, drove a truck for the U.S. Postal Service. As part of his duties, Henry carried a gun. One day, a police officer saw him and warned him that in that area, Black people weren’t allowed to have guns. A tense standoff ensued, ending in Henry speeding away all the way to Washington, D.C. From there, he called Kennedy’s mother and told her to pack up: They were moving.

“My family history has been profoundly influential on my views on race,” said Kennedy, who noted in an interview with The Harvard Gazette that race was a constant topic of conversation in his household when he was growing up. “I was born in Columbia, South Carolina, but I grew up in Washington, D.C., because my parents were afraid for their future in South Carolina. I asked my father once why he moved. His response to me was, ‘Because either a white man was going to kill me or I was going to kill a white man.’”

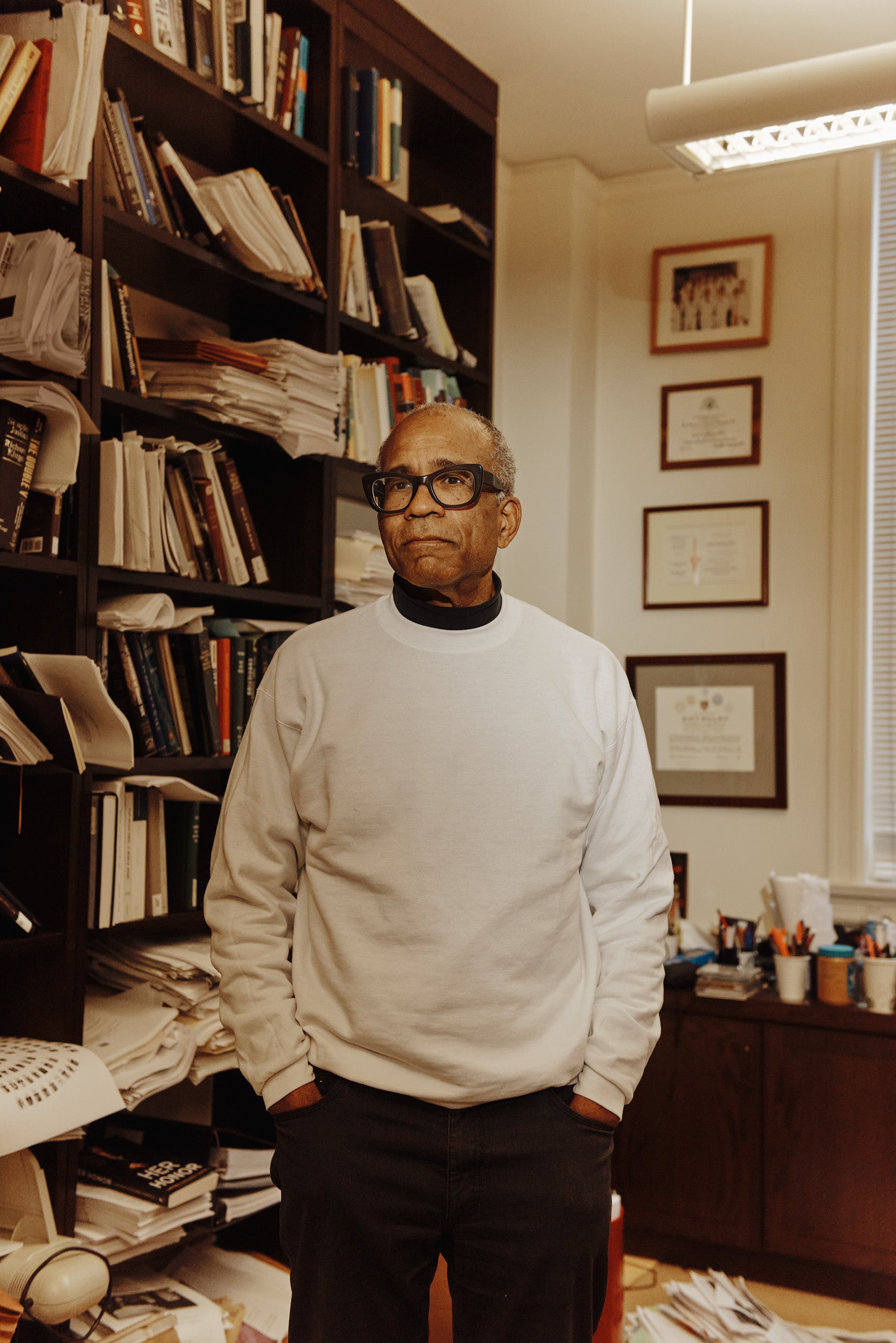

Kennedy was deeply impacted by his father, whom he calls in his seventh and latest book, a “racial pessimist through and through.” “Say It Loud!: On Race, Law, History, and Culture” is a collection of almost 30 essays written over the last three decades, in which Kennedy grapples with how experiences — from his own family’s racial persecution, to the election of the United States’ first Black president, to the murder of George Floyd — shaped his views on the central racial issues of our times. The essays trace Kennedy’s uneasy transformation from a confident optimist regarding America’s progressing path toward racial justice, to someone who “evince[s] hopefulness largely out of habit and a forlorn yearning on behalf of [his] children” but who does not expect in his own lifetime “to glimpse, much less enjoy, a progressive racial promised land.”

Born in the Jim Crow South in 1954, just four months after the Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board of Education, Kennedy witnessed the end of legal segregation. He spent his childhood summers in South Carolina, where he remembers he could not enter any public parks, because local officials had chosen to close them rather than obey orders to desegregate.

Transcending racism and segregation, Kennedy’s parents raised three children who would each go on to graduate from Princeton University and then pursue legal careers. Kennedy flourished in his chosen field: After graduating from college, he studied at Oxford University on a Rhodes Scholarship, then earned a law degree from Yale. He clerked for Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, whose name had been a fixture in the Kennedy household. Henry Kennedy had often spoken about having watched Marshall argue a case in a district court. He’d been amazed to see a white judge call the lawyer “Mr. Marshall,” a title never bestowed upon Black men in the Jim Crow South. In an interview for the Bulletin, Kennedy described introducing his father to Marshall, on the penultimate day of his clerkship, as one of the most meaningful experiences of his life.

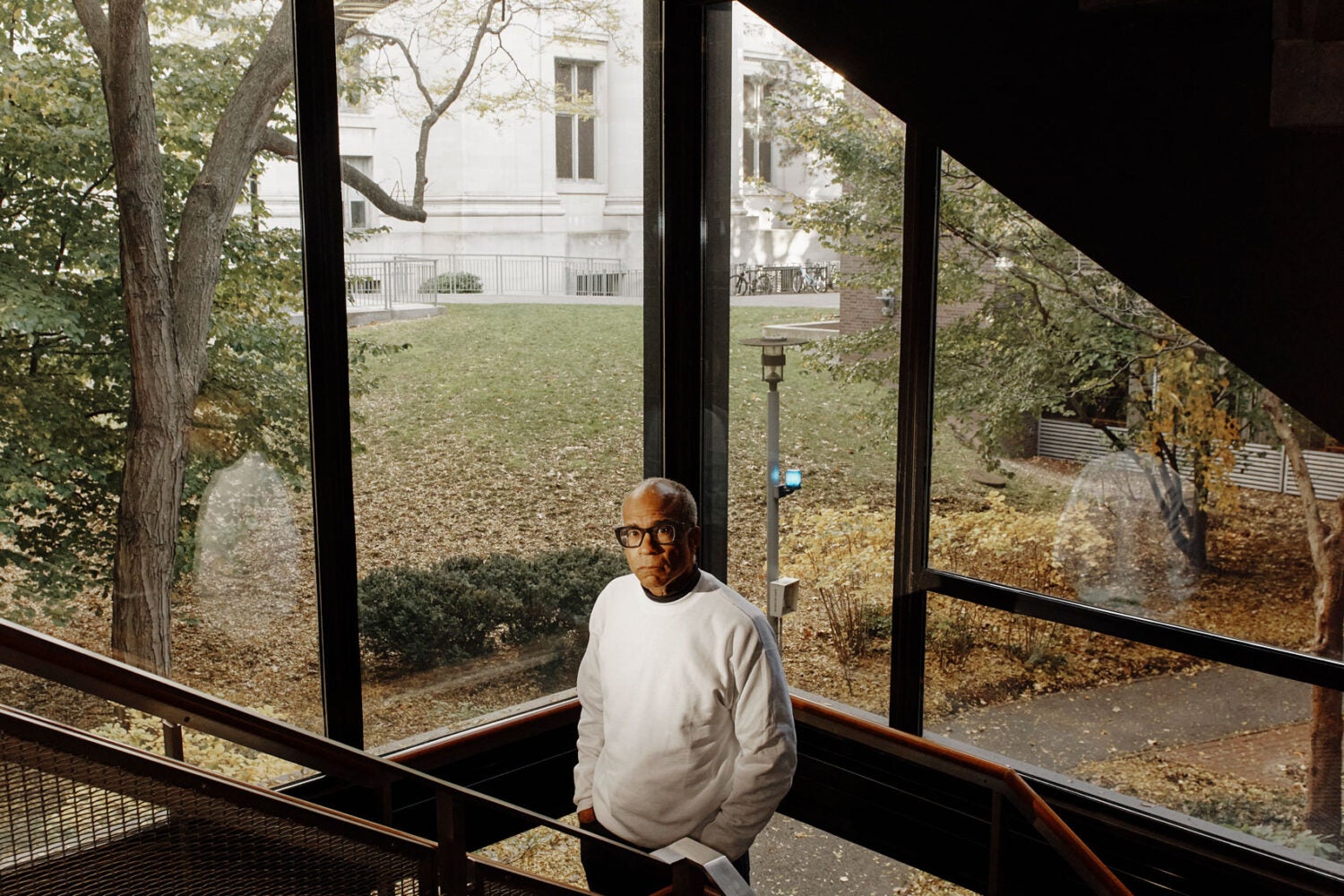

After completing his clerkship, Kennedy joined the HLS faculty in 1984, and he has remained there ever since. HLS Professor Martha Minow interviewed him for a faculty position. “I remember being dazzled,” she said. “He was just so filled with ideas.”

Reflecting on how much the world has changed since his childhood summers in South Carolina, Kennedy believes that though race remains a key and central issue in the United States, questions of race loom less large than they did in his youth. He cited one simple example: When he was growing up, if he wanted to sleep over at a friend’s house, the race of the friend would inevitably come up and be a “big deal” in his house. For his three children, all born in the 1990s, none would think to mention the matter.

Such evolutions in his everyday, personal experiences, coupled with major public milestones such as the ascension of Black Americans to the upper echelons of government, academia, corporations, and the military, led Kennedy for some time to feel sanguine about his general outlook on American race relations. He was confidently optimistic that the United States would continue to become a more just and equal society, even while he remained sharply aware of the limits to racial progress. For Kennedy, the last few years have been deeply eye-opening.

In the collection’s longest essay, Kennedy explores how his lifelong optimism stood in stark contrast to the pessimism embodied by former HLS Professor Derrick Bell, who joined Harvard Law School in 1969 and became the school’s first tenured Black professor in 1971. Bell originated the Race, Racism, and American Law course at HLS, which Kennedy inherited when Bell left Harvard in protest over the law school’s lack of faculty diversity at the time. As Kennedy notes in the unflinchingly honest and self-aware essay, Bell was deeply critical of how Kennedy later taught the course: He accused Kennedy of spending too much time challenging civil rights positions by delving into contrasting viewpoints rather than arming his students with winning arguments on favored policy positions.

Bell passed away in 2011, so he would never learn that in the end, Kennedy has had his core beliefs upended by recent events. Followers of Bell, Kennedy concedes, would have been far better prepared for the deep racial divides that swept into the foreground during the election and presidency of Donald Trump. “The last few years have been full of disappointment, full of trepidation, full of menace,” Kennedy said. “I thought that there were certain things in American life that were securely in the past. Tragically, I was wrong.”

“I thought that there were certain things in American life that were securely in the past. Tragically, I was wrong.”

“Say It Loud!” is a quieter book than its title might suggest. Kennedy rarely seeks to convince his readers of self-evident truths or rally them into unwavering positions. His research cites historical writings and anecdotes, statistics, and contemporary divisions to explore why issues are hard, not why they are easy.

According to Minow, his longtime colleague, these writings embody what sets Kennedy’s scholarship apart. “He is a public intellectual of the first order in the United States in a time of enormous division and polarization,” she said. Minow has long been struck by Kennedy’s “openness to different points of view, ability to put emotion aside and just talk through issues, his willingness to see the other side even when he has a strong view, and his courage. Frankly, we could use a lot more of what he brings to the world.”

Kennedy once advocated what he called “mandatory optimism,” an obligation for those espousing progressive politics to display hopefulness in order to maintain morale. But recently, he has begun to abandon his former position, preferring a more direct approach that avoids predicting how others may react to his views. He wants to be free as an intellectual to say what he thinks “and actually be free of the burden of being really concerned about the consequences.” His comfort with bucking trends has made him hard to pigeonhole, and his ideas have resonated, at different times, with people across a range of perspectives.

In an era when universities are quick to rename or rebrand buildings or symbols that honor bygone figures with problematic views, Kennedy questions whether such actions are always truly necessary, and where universities should draw a line. In one essay stemming from a 2019 Nation article, he argues that Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas turned his back on the Black community by using his position of power to take positions that undermine efforts that Kennedy believes would promote racial equality. In the book’s very next essay, which draws on articles published in 2018 and 1997, Kennedy critically examines the song from which his book takes its title, James Brown’s classic anthem of Black pride, contending that there is danger in seeking solidarity borne of traits that are inherited — such as race — rather than earned or acquired.

Kennedy recognizes, and at times seems to cherish, the tensions inherent in his sometimes conflicting and evolving views. “Social relations are complex and messy,” he explains in the preface. And in Kennedy’s view, carefully exploring tense and difficult issues is exactly what public intellectuals are supposed to do, even if that means refining or even rejecting their own prior positions. “People who have the great privilege of living their lives in an academic setting, where you’re constantly reading, you should be thinking and rethinking,” he said. “I don’t mind changing my mind and I don’t mind saying I was wrong. There’s no sin there.”