William Brennan ’31 and his complicated relationship with Harvard Law School

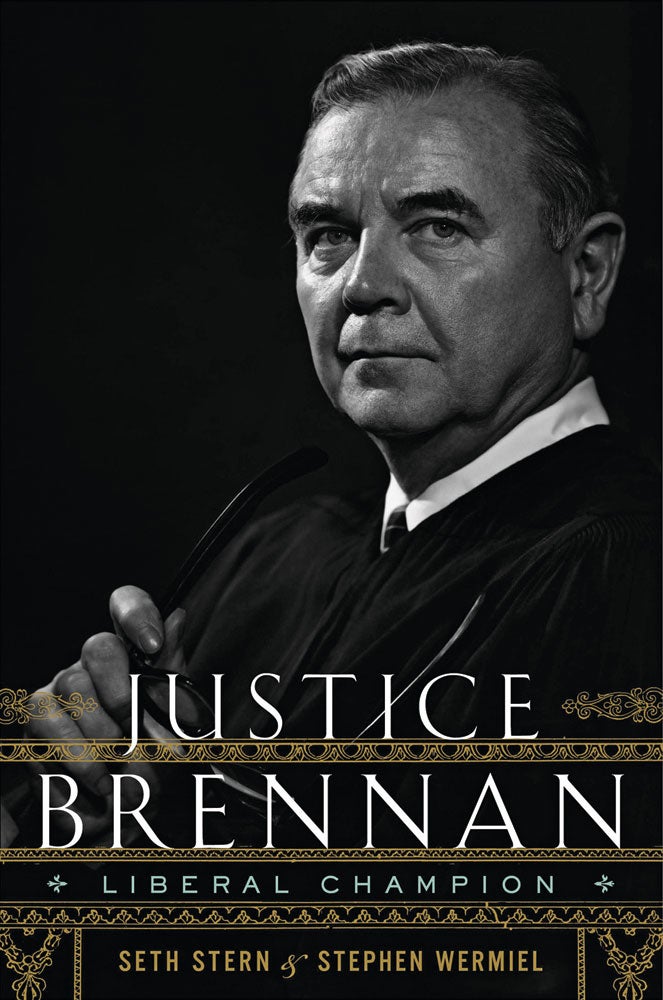

Seth Stern ’01, a legal affairs reporter for Congressional Quarterly, recently completed “Justice Brennan: Liberal Champion” (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010) with Stephen Wermiel. The biography weighs in at more than 500 pages, and included among them is the story of Brennan’s brief disaffection with HLS and the thaw that ended it, an episode described by Stern below.

The reaction from Harvard Law School was decidedly cool 54 years ago when President Eisenhower appointed its alumnus William J. Brennan Jr. ’31 to serve on the Supreme Court.

Few were more surprised by the choice of this little-known New Jersey judge than his law school classmate Professor Paul Freund ’31 S.J.D. ’32 and the man who had taught them both: Justice Felix Frankfurter LL.B. 1906.

Embarrassed to have been quoted by the Harvard Law Record predicting Brennan would become a “great justice,” Freund privately wrote Frankfurter, “I can only hope that my spurious prediction will turn out to be one of those self-fulfilling prophecies.”

Frankfurter harbored his own misgivings about Brennan, who was not among the favorite students he had invited to join his seminars and Sunday teas or later funneled to New Deal agencies after his friend, Franklin D. Roosevelt, became president.

The tepid reactions from Freund and Frankfurter ushered in what proved to be a rocky first decade in the relationship between Harvard Law School and its seventh alumnus to join the nation’s highest court.

Things went well at first, particularly when Brennan opted to follow Frankfurter’s advice and enlist Freund as his sole supplier of law clerks. Frankfurter could conceive of no other source.

“If you want to get good groceries in Washington, you go to Magruders,” Frankfurter once explained. “If you wanted to get a lot of first-class lawyers, you went to the Harvard Law School.”

But Frankfurter grew increasingly disenchanted with his former pupil’s direction as Brennan aligned with the bloc of liberals.

Brennan joked about Frankfurter’s disappointment during a speech at the Harvard Law Review’s annual banquet in April 1959. “I was a student of Professor Frankfurter,” said Brennan. “And when we disagree on the Court—perhaps you have noticed that this happens not infrequently—he observes that he has no memory of any signs in me of being his prize pupil.”

A few months later, their conflict spilled out in the pages of the Harvard Law Review, where Henry Hart, a leading constitutional scholar and longtime Frankfurter disciple, criticized one of Brennan’s recent opinions.

Brennan mostly took Hart’s criticism in stride, just as he had when Harvard Law School’s admissions committee rejected his son in 1955. Brennan still accepted an invitation in 1962 to judge HLS’s moot court competition, and he spoke at the Legal Aid Bureau’s 50th anniversary banquet the following year.

Brennan had never viewed the school with Frankfurter’s reverence. He enjoyed recounting the story of his first appearance in a New Jersey courtroom as a young lawyer, when the judge presiding over the case mocked him for using words a witness could not understand. “You see, he’s a Harvard graduate and he doesn’t speak English,” the judge said.

But Brennan could not forgive his alma mater when he was passed over for a seat on the school’s Visiting Committee in 1963 in favor of his colleague John M. Harlan.

Dean Erwin Griswold ’28 S.J.D. ’29 later said no slight was intended; the school simply wanted to fill the Visiting Committee with men of “varied backgrounds.”

Brennan did not see it that way. He never said anything about his hurt feelings to Griswold or anyone else on Harvard Law’s faculty, but he shared his disappointment with his clerks.

“It was a case of Harvard picking its ideological heir rather than one of its own sons,” said Stephen J. Friedman ’62, who clerked for Brennan during the October 1963 term.

Brennan later told the book’s co-author, Stephen Wermiel, that there was no connection to the perceived slight, but in April 1965 he informed Professor Freund that, after nine years, his role—and Harvard’s monopoly—in supplying law clerks was coming to an end.

By April 1966, word of Brennan’s disaffection had reached Griswold, who extended an invitation to join the Visiting Committee. Griswold also approached Professor Frank Michelman ‘60, the first clerk of Brennan’s to join the Harvard Law faculty, looking for a way to honor the justice, and then settled on the idea of commissioning a portrait, which was unveiled during a weekend-long celebration in 1967.

A few months later, Brennan returned to campus as a featured speaker at the school’s 150th anniversary celebration. “The school has not been content to rest on memories of a Golden Age—an age of giants, now legendary,” Brennan said. “After 150 years, I sense no lessening of vitality. Indeed, I am confident that the school’s great days are still before it.”

[pull-content content=”

Questioning the questioner

eth Stern ’01 has been a legal journalist since he graduated from law school. Below he takes his turn answering the questions.

How did you come to work on this book?

My co-author, Steve Wermiel, who was then covering the Supreme Court for The Wall StreetJournal, started this biography in 1986. After years of research, including 60 hours of interviews with Justice Brennan, Steve was looking for a partner by 2006 and sought out a fellow lawyer-journalist. Given the exclusive access Justice Brennan had granted Steve and the interviews he had conducted, this really was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

What have you learned about Justice Brennan that surprised you most?

I am particularly fascinated by the tensions between Brennan’s personal views and some of the positions he took as a justice. There is this notion that he was a liberal activist who wrote his personal preferences into law. In fact, no one infuriated this champion of press freedoms more than reporters. He wrote seminal women’s rights decisions in the 1970s even as he refused to hire female clerks. He personally opposed abortion but signed on to Roe v. Wade after helping lay the groundwork for it in prior decisions.

How do Americans remember him?

I’m struck by Brennan’s enduring relevance 20 years after his retirement. After President Obama took office, liberals invoked Brennan as just the sort of passionate and persuasive justice they want on the Court. Law students, who were toddlers when he retired, post messages on Twitter holding him up as their hero. But it’s also true that progressive legal scholars have become increasingly uneasy with Brennan’s vision of a “living Constitution.” Liberals are still groping for an alternative that resonates with the public as well as the brand of judicial restraint so effectively marketed to the public by conservatives.

Are there issues where you found yourself disagreeing with Brennan?

We sought to write the book down the middle, and there are a number of places where I took issue with Brennan’s approach. I came to question how much he relied on human dignity as the value underlying his death penalty dissents and other decisions. But I also came to admire Brennan deeply for the way he applied the concept of human dignity in his own life. He treated everyone at the Court—including the maintenance staff and police officers—with the same respect and affection.

How has writing this book influenced the way you think about today’s Court?

I’ve learned that the Supreme Court is an institution where change often comes slowly. It was six terms before Justice Brennan’s bloc of liberals got their fifth vote after Arthur Goldberg replaced Felix Frankfurter in 1962. That’s when Hugo Black finally could turn a quarter century’s worth of dissents into majority opinions. Except in those instances where a new justice dramatically alters the Court’s ideological balance, I don’t think it’s realistic to expect a new arrival such as Elena Kagan to come in and shift the Court’s direction.” float=”center”]