At first, the app looks a little like the original Facebook feed, or perhaps a stripped-down version of Twitter. But start typing, and it becomes clear something is very different about Minus, a social media platform and work by Ben Grosser, an Illinois-based artist whose piece was featured in a metaLAB exhibition at Harvard Art Museums this spring.

The odd thing about Minus is that every time you submit a post — whether it is a response to someone else, or a new thread — a countdown informs you of how many posts you have left. Because once you hit the lifetime limit of 100 posts on Minus, you’re done. No exceptions.

How does this influence what you say, and to whom you say it? How does it change how you interpret others’ comments, knowing they are bound by the same restriction? And what exactly does being part of a social network like this mean?

These questions and many more were explored in “Living by Protocol,” a group art exhibition organized by metaLAB (at) Harvard & FU Berlin, a project of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard Law School and Freie Universität Berlin. The exhibition was organized by metaLAB principals Kim Albrecht and Sarah Newman, and reflected on the many ways social media influences our lives, relationships, and the world around us, for good and for ill.

It also investigated options for the future. The show was a natural complement to the work happening at BKC, says Newman, “since BKC is, and always has been, a place that welcomes experimentation, interdisciplinarity, and alternative forms of scholarly engagement.”

“The Berkman Klein Center is approaching social media from a law perspective — how to deal with social media, what to do about Facebook,” adds Albrecht. “What I find so intriguing is that art has some intriguing ideas and concepts that are different from what academia is thinking about.” The exhibit, he says, was an opportunity “to showcase this range and playfulness, to display alternative realities that social media might or could be.”

Newman and Albrecht have also brought their perspectives to the Institute for Rebooting Social Media, a research initiative at BKC: they co-led a public workshop for the Institute in the fall, and Newman also serves as an adviser on that team. She says the exhibition enabled the public to experience novel and critical perspectives of social media through sensory modalities. “So much of social media content and design is visual, but a lot of the discussion about it takes the form of traditional text in articles, books, and papers. We thought, ‘why not use the visual medium to explore this?’”

“Unerasable Characters II” by Winnie Soon displays in a grid pattern the daily censored tweets from one of China’s largest social media platforms. Credit: Lorin Granger

A few of the pieces, like Minus, are reimagined versions of social media applications, says Albrecht. Others probe the use or abuse of data, or are meditations on social media from a philosophical perspective.

But Newman and Albrecht are clear that the exhibition did more than simply point out where social media has gone wrong. “All of the pieces are deep and nuanced,” says Newman. “Even in the moments where they might be celebrating a certain aspect of the technology, and leveraging beauty, levity, or humor, they simultaneously retain a critical stance toward social media.”

Newman’s own piece, with Jad Esber, called “All the Things I Want and Don’t Want,” features a collection of peoples’ self-reported best and worst experiences on social media, challenging viewers to absorb these myriad encounters in all their complexity. The text flits by quickly in a way that is unsettling yet difficult to ignore. “It has this kind of addictive quality, when you’re watching the paper flip over, as if you’re scrolling a feed,” says Newman. “You keep looking for the thing that is good, while you’re also being bombarded by things that are bad. Social media is a complex landscape — it’s not all bad — which is why all of this is so challenging.”

Mirabelle Jones’ “Artificial Intimacy” presents LGBTQAI and BIPOC people conversing with a chatbot version of themselves based on their social media profiles. It questions the values embedded in voice assistant programs and the depth of personal information collected in a user’s social media profile.

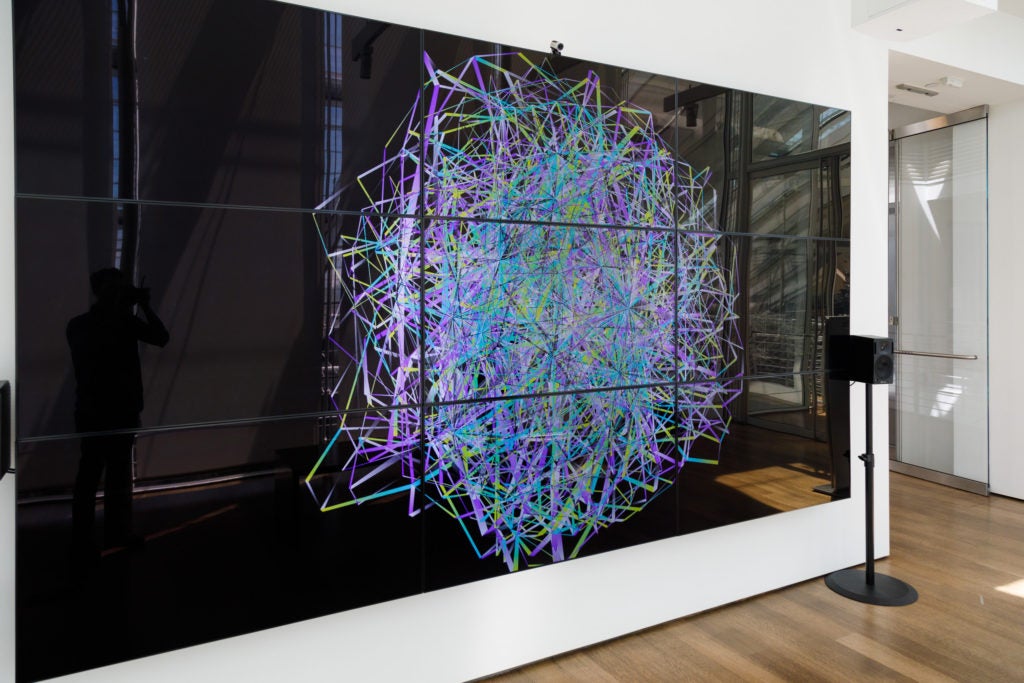

Albrecht, whose abstract work of points and lines shifts and moves in beautiful and strange ways, is an investigation of the spaces — or non-spaces — that make our ultra-connected world possible.

“Wendy Chun, a media theorist, has this idea that the important thing about networks is not the networks themselves, but the spaces in between,” explains Albrecht. “I tried to find a visual mode of representing that ‘non-networked’ space. Networks are often visualized using a method called force-directed graph drawing. You have points that drift away from one another. If they’re connected by lines, they get pulled together. What I am visualizing is not the network itself but the past traces of the algorithm, you see colors that are overlapping, emerging, and filling the space, but you never see the actual network. Only where it has been.”

While each of the works in “Living by Protocol” inspects social media in a different way, Newman says that many of the pieces explore where humans and human nature are situated (or neglected) in these networks. The works ask “[w]hether the human is made invisible, whether the human is at the forefront, and how social media plays on human psychology or human needs,” she says.

These artistic explorations can and do interact with law, science, and other fields in surprising ways, adds Albrecht. He points to the artist Jackson Pollock, whose abstract drip paintings were initially panned by some critics, but were later discovered to embody patterns, such as fractals, found across the natural world.

“Art has a more open conception of how to interrogate the world. It does not have the kind of restrictions that science often has,” Albrecht says.

In other words, art can predict and sometimes inspire future solutions. “That, for me, is its great power. The hope is that these ideas trickle down, and there is a discussion between art and all these other fields.”

Living by Protocol was on view at Harvard Art Museums Lightbox Gallery, and was supported by a grant from the David Bohnnet Foundation.