An Essay by Robert E. Bradney ’50

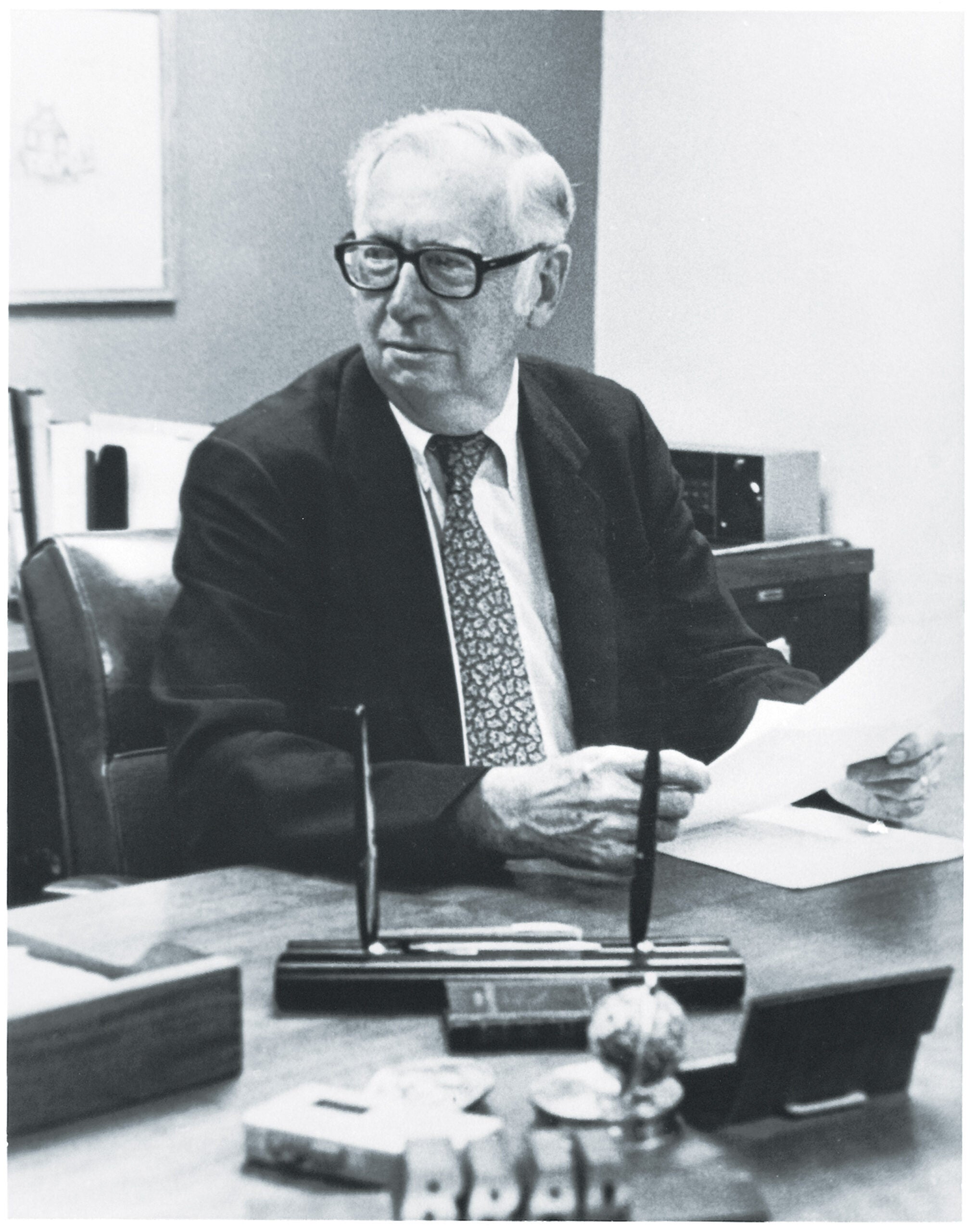

One cold day in the winter of 1950, I was enrolled in a course titled Federal Taxation taught by the dean of the law school, Erwin Griswold ’28 S.J.D. ’29.

Dean Griswold taught as he practiced and as he lived, with a tremendous aura of authority. There was little doubt as to what the subject matter was, nor was there doubt as to his approach.

The class was large; I forget exactly how many, but the students occupied most of the seats in one of the lecture halls at Langdell. Dean Griswold used a seating chart. Typically he would make some substantive comments, then ask the person whose turn it was to state the case. The student would then be interrogated as to what the case meant.

There was little doubt as to when one was going to be called upon. No more than that experienced by one who is standing third in line to be guillotined.

On this cold day in January, Dean Griswold made his substantive remarks and then asked Mr. Smith (name changed for purposes of mercy) to state the next case. The following ensued:

“I’m sorry. I’m not prepared.”

Anyone who ever had an experience with Dean Griswold can testify that on some of his better days, his countenance was somewhat like that of a pit bull with indigestion.

This was not one of his better days.

“Would you please repeat what you said.”

“I’m not prepared, sir.”

One could have heard a pin drop. It was to get quieter.

“Very well, Mr. Smith. Read the case now. We’ll wait for you.”

Although derivatives had not yet been invented, the case involved something that concerned taxation of something likewise esoteric. Something like whether the federal government had extraterritorial powers to tax the property if its situs were in Madagascar. The language used by the court did not tend to penetrate the brain of the reader with any degree of clarity.

Mr. Smith started reading silently. Very silently. If one could have heard a pin drop earlier, if one were to now drop one, it would have sounded like a cannon.

Einstein said (at least I think he did) that time is relative. Einstein was right. In Langdell Hall that day it stopped.

How much time passed? Sixteen centuries. It seemed at least that.

For all of that time there was that authoritarian body, standing in the podium, not moving a muscle, watching Mr. Smith turn the pages.

Lo, Mr. Smith finally finished and, to the amazement of his classmates, stated the case.

I might say that this did not happen again in the Federal Taxation course in the cold winter of 1950.

A postscript: I returned to central Illinois, where I became a trial lawyer and in over 40 years of courtroom experience tried everything from theories as to why sows couldn’t get pregnant to bid-rigging cases filed under the Clayton Act.

Let it here be said that, while I probably lost more cases than I won, I was never unprepared.