Arthur Miller ’58 and Paul Weiler LL.M. ’65 end their storied HLS teaching careers

This fall, the classrooms and lecture halls of Harvard Law School no longer reverberated with the voices of two of the institution’s best-known teachers—Professors Arthur R. Miller ’58 and Paul C. Weiler LL.M. ’65. Miller ended his 36-year HLS career last year, and Weiler retired after 26 years of teaching at the school.

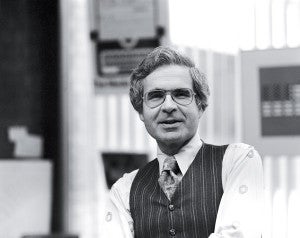

One of the nation’s most distinguished legal scholars in the areas of civil procedure, litigation, copyright and privacy, Miller joined the faculty in 1971. He is the author or editor of scores of articles and many books, including multiple editions of “Federal Practice and Procedure” (with C.A. Wright, some editions with E.H. Cooper, M.K. Kane and R. Marcus). He became one of the most widely recognized legal commentators in the nation through the syndicated TV program “Miller’s Court” and more than 20 years as legal editor for ABC’s “Good Morning, America.”

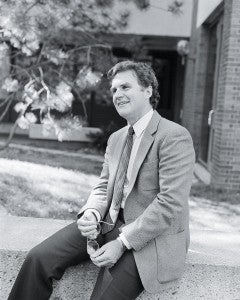

The Canadian-born Weiler has been described by Canada’s Financial Post as “the foremost labour law scholar in North America” but is also known as a leading expert on sports law. Before joining the HLS faculty in 1981, he served as an academic and arbitrator in Ontario and later as chairman of the British Columbia Labour Relations Board. He also advised the federal government of Canada on drafting the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and completed a comprehensive review of Ontario’s workers’ compensation system, resulting in the creation of the Workers’ Compensation Tribunal.

Weiler was appointed by President Bill Clinton as chief counsel to the Commission on the Future of Worker-Management Relations (the Dunlop Commission). He is the author of various books, including, most recently, “Sports and the Law” (1998) and “Entertainment, Media and the Law” (2002).

Here, two former students pay tribute.

America’s Law Professor

More than most, Arthur Miller has been a teacher in the public domain

By Tami K. Lefko ’94

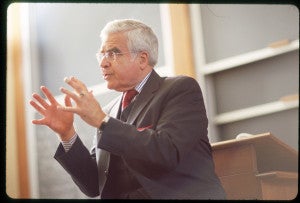

Within the legal profession, Arthur Miller is known first and foremost—and deservedly—as the pre-eminent scholar and teacher of civil procedure. He quite literally wrote the book that is probably the most widely used practice reference of all time—the multi-volume treatise “Federal Practice and Procedure,” first published in 1969. In 2007 alone, it was referenced more than 2,000 times in published federal court opinions. He is also known for his national media appearances, his accomplished career as a litigator (he has argued in front of the Supreme Court many times and also in front of every federal circuit court of appeals in the nation) and his pioneering publications on technology and privacy.

He has reached countless practicing attorneys and judges through his innumerable lectures to judicial conferences and other audiences and through the many influential books, articles, and treatises on procedure, complex litigation, and related topics that he has written and co-written. And, he has had a direct impact on the rules themselves, as a principal architect of the 1983 amendments to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

To me, though, he will always be first and foremost a copyright professor and scholar. Professor Miller loves copyright, and it shows.

It was apparent to me when I was a 2L, wait-listed for his class and hoping for a spot. When one didn’t open up, I continued to attend as an auditor. (I don’t think he knew at the time that I never got in, since I received a concerned phone call when I missed the final exam.) Luckily I was able to enroll as a 3L, happy to have the opportunity to take the class officially.

Like Professor Miller, I was drawn to the study of copyright by a love of music, movies and other works of art. I remember fondly our class discussions of “West Side Story” and “Romeo and Juliet,” of parodies like Sid Caesar’s “From Here to Obscurity,” and of iconic characters like Sam Spade, James Bond and Snoopy, labeled a “dog right out of central casting” to spur discussion. When we discussed whether California might declare Mickey Mouse a state treasure rather than allow him to fall into the public domain, I made note of the prospective date so that I could remind Professor Miller of his prediction; federal legislation in 1998 was not the precise method discussed, but it had the predicted effect.

Professor Miller’s copyright scholarship has examined new technologies in their historical context. In an influential article published in the Harvard Law Review in 1993, he set forth his views on protection for computer programs, databases and computer-generated works. Whereas others favored sui generis legislation to cope with information technologies, he expressed confidence in the ability of the copyright system to assimilate revolutionary technologies over time.

His career came full circle recently when he completed an article that he began nearly 50 years ago as a law student. In it, he proposes a functional approach, under which courts would examine whether protecting an idea would create an anti-competitive effect and whether the defendant materially benefited from the misappropriation. Like the copyright principles discussed in his 1993 article, he places a premium on flexibility over specificity, proposing a framework intended to withstand the vagaries of time.

Professor Miller recently wrote that he became fascinated with copyright as a law student and has “loved, litigated, taught and written on questions of intellectual property” ever since. From his scholarship to his teaching to his law practice, copyright, like civil procedure, has always been a labor of love for him. I have no doubt that will continue to be true, to the delight of his colleagues, clients and anyone fortunate enough to learn from him.

Tami K. Lefko ’94 is a contract attorney in Los Angeles who specializes in intellectual property and recently began her fourth year teaching legal writing at USC Gould School of Law.

Passion in His Playbook

If there’s ever a Hall of Fame for sports law, Paul Weiler is a shoo-in

By Michael McCann LL.M. ’05

The late Will McDonough, the Boston Globe columnist, once said: “When it comes to sports law, Paul Weiler knows the answer before you ask the question.”

In fact, for many law students, attorneys and professors, Paul Weiler is indisputably the founder of American sports law and the field’s most distinguished member, having virtually invented the specialty by merging his expertise in labor law with his love of sports. As one of his former students and now a colleague in legal academia, I appreciate him more and more every day.

Weiler’s passion for his subject—and for teaching it—has inspired countless HLS students to successfully pursue careers in sports law. Since he began teaching at Harvard Law School, an astonishing number of his students have become sports law scholars, agents, litigators, mediators and other professionals engaged in what is quite possibly the most competitive specialty within the law. Their success is a testament to the man who taught them things such as the powers of the commissioner, the legal ramifications of steroid use, the nuances of Title IX, the intersection of torts and sports, and myriad other topics that define the field that has so defined him.

Just consider, for a moment, the body of written work he has produced, and how his students can so readily draw on it. Most notably, he has co-written what is probably the leading casebook on the subject, “Sports and the Law,” as well as numerous law review articles and journal publications that have established and substantiated the growing canon of sports law scholarship.

And, aware that many people who aren’t lawyers will seek instruction in the topic, Weiler has also written more popularized sports law entries. The most significant among them is the transformative book “Leveling the Playing Field: How the Law Can Make Sports Better for Fans,” which, according to The New York Times Book Review, “combines the broad knowledge of an all-seasons sports fan with the clarity of an antitrust lawyer.” Reaching both an academic and a popular audience is never easy, and yet Weiler has done it with the adroitness and grace that have distinguished his career.

Weiler has also been the leading public advocate for sports law. He has testified before the U.S. Congress and met with politicians in Canada, his home country, on a seemingly boundless range of issues. Many leaders here and abroad consider him sports law’s leading guru.

The true essence of Paul Weiler, however, cannot be captured by the long list of his professional accomplishments, contacts and honors. Instead, it rests in his heart, in his soul and in his undying warmth. Like all of his former students, I can personally attest to his profoundly deep and unqualified compassion for everyone who seeks his guidance. I will never forget, nor fail to appreciate, the enormous amount of time, energy and emotion he spent with me on a paper that I would eventually publish in a law review. There were certainly many demands on his time—demands that seemed to me to be much more important. But never once did he put those demands ahead of me. Paul Weiler just doesn’t do that. His students always come first.

It may be just a coincidence that such a friendly professor held the prestigious Henry J. Friendly Professorship of Law, but it couldn’t be more fitting. As much as I hate to disagree with the late Will McDonough, when it comes to sports law, it’s not about the questions that Paul Weiler can answer. For me, as for so many others, Paul Weiler is the answer.