Here’s how a Boston resident became a victim of the foreclosure crisis. To protect her privacy, we’ll call her Beth Rede. Rede was disabled, living on Social Security disability insurance and sheltered in federally subsidized housing, when she was approached by a mortgage broker. The broker knew Rede was poor but persuaded her to buy a multifamily house, telling her that she could pay the mortgage from the rent she would collect from her tenants. Rede took two mortgages—one with an adjustable rate—totaling nearly half a million dollars, gave up her subsidized housing and moved into the multifamily. When the teaser rate expired and the adjustable rate “exploded,” Rede could no longer afford the loans. Her house ended up in foreclosure within two years of purchase. The original lender, meanwhile, had long since sold the mortgages to Wall Street banks that pooled them into trusts and sold them in bundles of mortgage-backed securities.

Last year alone, 12,233 home foreclosures were completed in Massachusetts, where foreclosure rates are considered elevated and are predicted to remain so. That number represents some people, like Beth Rede, who were deceived by predatory lenders. Others lost their jobs in the recession or suffered some other financial setback. Nearly all are victims of swashbuckling financial industry practices that cascaded into the housing bust, and shifted the profit-making center of home financing from returns paid by carefully selected borrowers, to the commoditization of increasingly risky mortgages.

One likely outcome of the crisis is street after street of shuttered homes, particularly in poorer neighborhoods of color where predatory lending, declining property values and unemployment hit hardest. But that doesn’t appear to be happening in Boston’s low-income neighborhoods of Dorchester, Mattapan and Roxbury, despite their high rates of foreclosure. The reasons for that are varied and complex, but among the contributing factors are Boston-based community organizations and their partnerships with institutions such as Harvard Law School.

This is the story of how the student-run Harvard Legal Aid Bureau and two teaching clinics at the school’s WilmerHale Legal Services Center—the Post-Foreclosure Eviction Defense Housing Clinic, which represents Beth Rede, and the Predatory Lending/Consumer Protection Clinic—are working together to use activism, community lawyering, bankruptcy to help redirect the path of the foreclosure wave in Boston.

Two achievements—one legislative, one judicial—have brought broad relief across the state. In August 2010, Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick ’82 signed into law a statute that was drafted, and lobbied for, by students from the Legal Aid Bureau. The statute prevents banks that own foreclosed properties from evicting tenants without just cause. Since its passage, no Massachusetts tenants have been evicted simply because they were living in foreclosed properties. “It is definitely fair to say that evicting tenants was routine prior to our statute,” says David Grossman ’88 (left), faculty director of the Legal Aid Bureau. He estimates that thousands of tenants across the state will be spared eviction because of the law.

The next victory came in January 2011, when the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court decided in U.S. Bank National Association v. Ibanez that a lender cannot foreclose on a property unless it can prove ownership of the mortgage. The Legal Services Center won the case for Springfield homeowner Antonio Ibanez. And the ruling sent shock waves throughout the financial sector, even though its reach is limited to Massachusetts: For the first time, a state high court was holding lenders accountable for their failure to properly record chain of title as they rapidly sold and resold mortgages for profit.

In the SJC pipeline are two more high-impact cases. In May, the court was scheduled to hear Bevilacqua v. Rodriguez, which picks up a loose thread from Ibanez: If a bank conducts an unlawful foreclosure sale and transfers the property to a real estate speculator or investor, who has title? The Legal Services Center’s Predatory Lending/Consumer Protection Clinic run by Roger Bertling and Max Weinstein argued in an amicus brief that such a sale would unlawfully strip a homeowner of legal title, and that the investor’s remedy is through title insurance.

The other case, Bank of New York v. Bailey, heard by the SJC in April, looked at whether the Boston Housing Court was correct when it decided that it lacked jurisdiction to consider the validity of the foreclosure underlying an eviction case. Legal Aid Bureau student Jennifer Tarr ’11 represented the homeowner. “This case is part of a wave of change,” says Tarr. “I’m privileged to be part of that.”

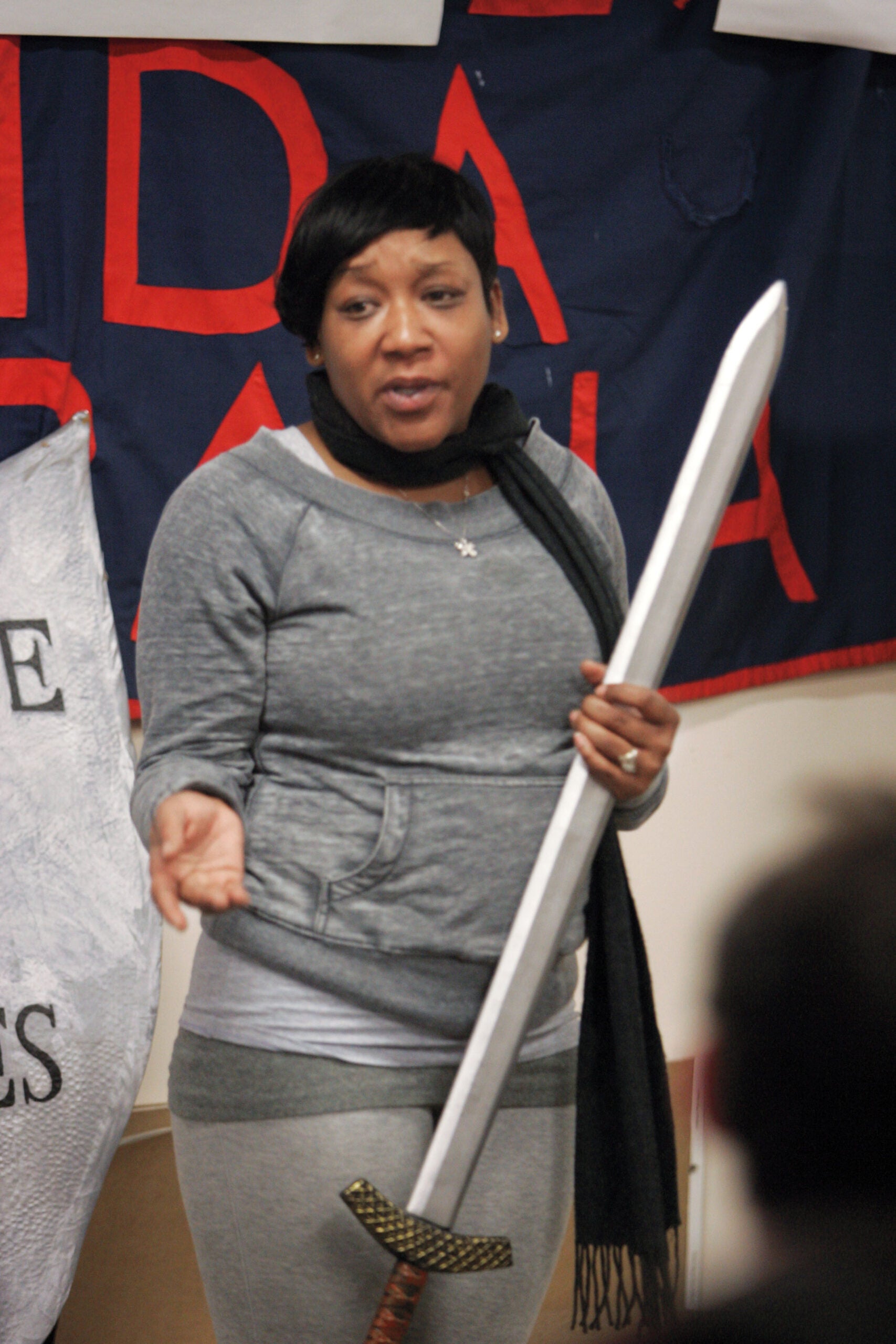

What Tarr means by “wave of change” is Boston’s active anti-eviction movement, which is fueled by the intense community organizing work of groups like City Life/Vida Urbana and supported by area legal clinics, with Harvard Law School playing a major role. HLS supports the movement through community lawyering as well as individual representation, with a high degree of strategic coordination between the school’s Legal Aid Bureau and the Legal Services Center.

HLS students litigate predatory lending cases, negotiate loan modifications, fight fraudulent “rescue” scams, handle bankruptcy matters and otherwise represent individuals whose properties have been foreclosed on. They also help clients working with Boston Community Capital, a nonprofit community development financial institution that buys foreclosed properties and sells them back to qualifying former owners at current market value with mortgages they can realistically afford. And in a lemons-to-lemonade strategy, they are pushing banks to delead their foreclosure-acquired properties. “If banks are invading the neighborhood, we might as well get a benefit out of it,” says Clinical Instructor Maureen McDonagh.

Community lawyering, meanwhile, is primarily coordinated through the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau. Its Foreclosure Task Force works with Project No One Leaves, a student group founded in 2007 by Nick Hartigan ’09, David Haller ’09, Eric Herrmann ’09 and Tony Borich ’09 to keep people in their homes, post-foreclosure. Students knock on the doors of foreclosed homes, inform residents of their rights and urge them to attend meetings of City Life/Vida Urbana, a grass-roots community organization, where they learn how to fight eviction through direct action and demonstrations—and where Harvard Law students provide legal advice, often late into the night.

Students also run a weekly law clinic for occupants of foreclosed properties; provide pro bono representation through the Lawyer for the Day program at Boston Housing Court; and track newly docketed housing court cases and reach out to people facing eviction. They’ve won dozens of significant verdicts and settlements for tenants—some in the low six figures—against banks not keeping homes in good repair after foreclosure. These are the highest settlements and verdicts on cases of this type in the country.

“We utilize both legal and public pressure to get banks to change their policies about displacing people after foreclosure,” explains Grossman. “We don’t want Boston boarded up like other cities.”

The experience of Ken Tilton, a client of the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau, attests to the life-changing nature of the joint work of City Life/Vida Urbana and HLS. He and his partner of 26 years, Frank, owned two retail stores and a restaurant when they bought their single-family home in Roxbury in 2004. Everything was fine until Frank got sick with cancer in 2006. With Tilton focused on caring for Frank, they eventually lost the stores, and the situation at the restaurant grew precarious. Frank died in 2008, and Tilton fell into a deep depression. Ominous letters began arriving from the bank. But then: “In 2008, someone banged on my door. It was two students. They were from City Life,” Tilton recalls. He attended a community meeting. “It was an immediate cloud off me because I realized there was help out there,” he says. “I watched the legal process, the vigils, and the blockades, and I became passionate about the cause.” While his future is uncertain, he says he no longer fears going to court, thanks to the zealous representation of Legal Aid Bureau students Tarr and Samuel Levine ’12.

Levine, who is president of the Legal Aid Bureau’s Foreclosure Task Force and outreach director for Project No One Leaves, reflects on the lessons he’s learned watching people like Tilton move from hopelessness to empowerment. “There is a lot of leverage beyond what the court system can provide. Power can be created outside the courts,” he says. “You go to law school classes, read cases and statutes, and think that’s the authority. But I’ve learned that there are lots of ways for people to claim power and rights.”