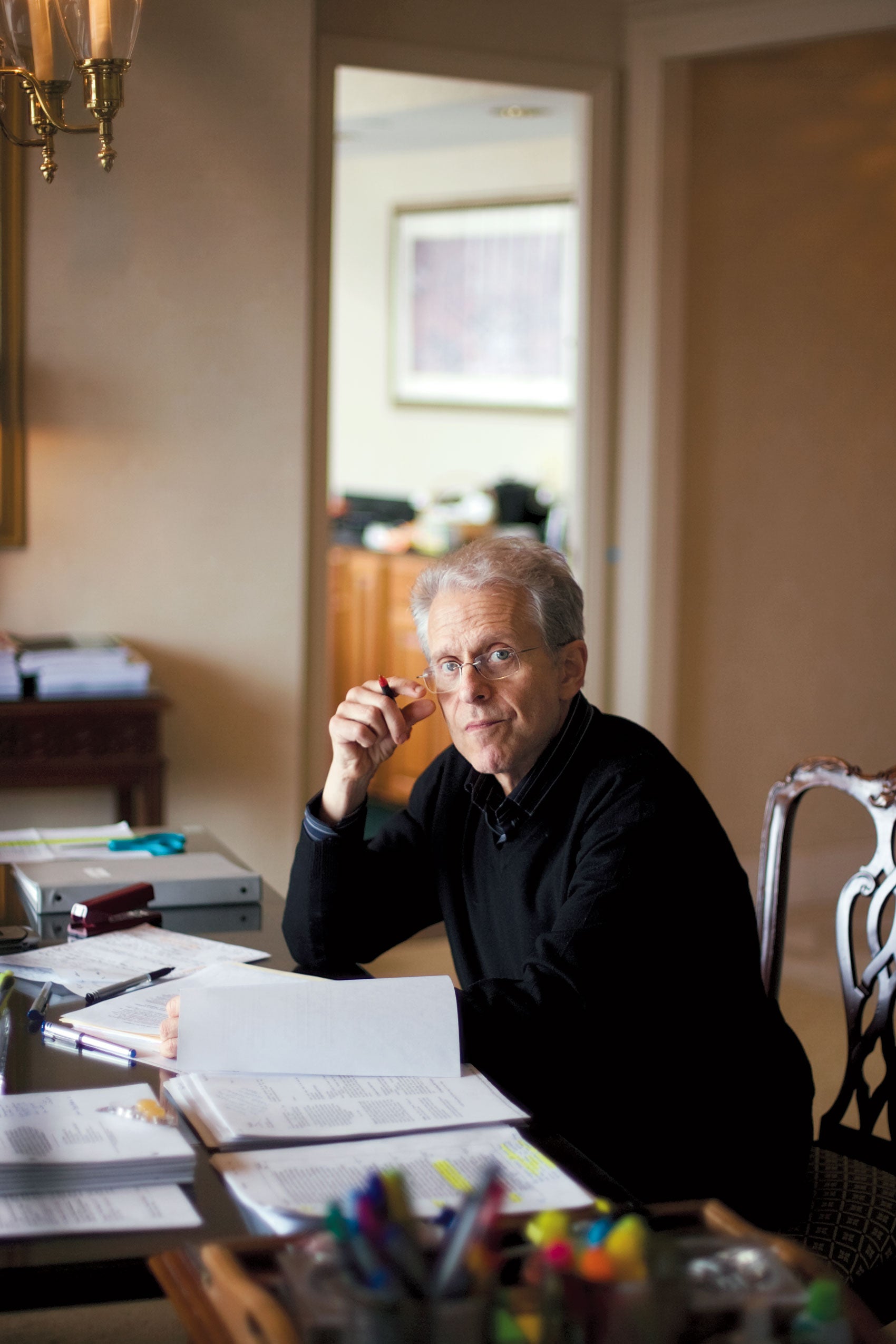

Friday evening, less than three days before he is to argue his 35th case in the highest court in the land, Laurence Tribe ’66 is working quietly in a suite at the Watergate, as a major blizzard paralyzes much of the Atlantic seaboard.

A handful of Harvard Law School students who have been assisting him are stranded at Logan Airport in Boston. It’s not clear that they will even make it down before Monday’s argument, let alone help him with the myriad last-minute tasks that he has for them.

Still, there is e-mail, and Tribe sends assignments and requests to the 23 people—associated counsel, assistants and students—who make up his team. He also sends messages to his client, Frank Robbins, a Wyoming rancher whose case has brought him to the United States Supreme Court—“the last place on God’s green earth I ever imagined I would be,” Robbins says later.

In 1994, Robbins bought the High Island Ranch in Hot Springs County, Wyo., intending to run it as a guest ranch and to raise his 8,000 head of cattle there. What he got with the deed turned out to be a 13-year standoff with federal officials over access to his land—and litigation that has nearly ruined him. It was the beginning of a Western saga that could succinctly explain the sentiments behind the phrase “sagebrush rebellion.”

A month before Robbins bought the ranch, the prior owner granted the Bureau of Land Management an easement so that bureau officers could gain access to adjacent federal lands. The situation was not uncommon in that part of the West, where federal, state and private parcels are interlocked in a symbiotic crazy quilt of easements and grazing rights.

But in a snafu of the kind one might find in the fact pattern of a bar exam question, the BLM failed to record the easement. When Robbins bought the property—with no knowledge of the easement—he was able to record his title in Hot Springs County free of that encumbrance.

After BLM officials realized their mistake, they contacted Robbins to discuss a new easement. According to court documents, they didn’t just ask for one—they demanded it. Robbins, who says he had been willing to negotiate a deal, refused, citing the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution, which provides that “private property [shall not] be taken for public use, without just compensation.”

BLM officials then embarked on what Robbins says was a long-term campaign of intimidation and retaliation. They stopped maintaining a road leading to his property, canceled his right-of-way across federal land between the ranch and a public road, revoked his grazing permits, interfered with his cattle drives and guests, and, in one instance, threatened to “bury him.” There was also evidence that they broke into a lodge on his property.

When his cattle strayed onto federal lands, BLM officers wrote him up for trespassing, ignoring similar breaches by other ranchers. They also persuaded the local U.S. attorney to charge him with the felony of interfering with federal officers—and then offered to make the charge disappear in exchange for granting the easement. He refused.

At the criminal trial on the interference charge, the jury took less than half an hour to acquit Robbins. But in addition to suffering through the ordeal of a trial, he had racked up huge legal bills, some of them arising from all the little citations that had been issued over four years.

In 1998 Robbins decided to sue the BLM officers who had been pressuring him.

Ordinarily, people challenging the actions of federal agencies sue under the Administrative Procedure Act and several similar statutes governing administrative action—the avenues that courts usually insist plaintiffs take when seeking relief from agency rulings or directives. But Robbins was not disputing formal agency decisions so much as seeking accountability for a pattern of allegedly lawless conduct by particular agents.

Instead of suing the bureau under the APA, Robbins filed suit in federal court against six employees of the BLM in their individual capacities for violations of what he claimed was his clearly established Fifth Amendment right to exclude the government from his property and to be free from coercive attempts to obtain that property through methods other than a lawful exercise of the government’s power of eminent domain.

He brought that claim under the authority of Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of the Bureau of Narcotics and the line of cases holding that federal officers who intentionally violate a “clearly established” constitutional right can be sued personally for damages, and cannot hide behind a claim of official immunity.

Aided by Cheyenne attorneys Karen Budd-Falen and Marc Stimpert, Robbins also alleged that the BLM officials had engaged in a pattern of extortion and blackmail in violation of the civil provisions of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act. Although officials have been sued under the civil provisions of RICO—or prosecuted under its criminal provisions—for extorting a personal benefit, Robbins’ RICO claim was unusual because it sought relief for action by officials who had tried to obtain a benefit not for themselves but for the government.

Today, nearly 10 years since Robbins filed suit, the case has still not gone to trial. Instead, it has bounced several times from federal district court to the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals and back, in litigation over the government’s motions to dismiss or for summary judgment—and now, in an interlocutory appeal, to the Supreme Court, on the government’s petition for certiorari after the 10th Circuit cleared the way for a trial.

The Court granted cert in Wilkie v. Robbins to decide several questions, including one that gives it the opportunity to expand (or limit) the scope of the property rights that are encompassed by the Fifth Amendment—specifically, whether the amendment protects against retaliation for exercising a right to exclude the government from one’s property when it is not engaged in a lawful taking. The 10th Circuit said yes—the first time a federal circuit court had explicitly ruled that such a right is protected.

If the Supreme Court recognizes such a right, it will also decide whether that right was “clearly established” in this case, for purposes of evaluating Robbins’ claim that the BLM officers knew or should have known they were violating it.

The Court also agreed to hear whether Robbins’ Bivens action is precluded by the availability of judicial review under the Administrative Procedure Act or other statutes for pursuing grievances against administrative action.

Finally, the Court certified the question whether government officials acting pursuant to their regulatory authority can be found liable under RICO for the predicate act of “extortion under color of official right” for attempting to obtain property for the sole benefit of the government, and if so, whether in this particular case that statutory prohibition was clearly established when they allegedly did so.

Tribe entered the case at the invitation of Robbins after the government filed its cert petition. For Tribe, it was a chance to involve students from Harvard Law School’s Supreme Court litigation clinic, which brings advocates to campus to moot their cases before arguments in the Court and provides students with opportunities to work on cert petitions and other briefs.

“I believed that the government’s position was both wrong and dangerous and the rancher-respondent’s position was correct and ought if possible to be vindicated,” says Tribe. “The case seemed challenging, interesting and pedagogically valuable for the students in the Harvard Supreme Court litigation clinic … so I offered to brief and argue it pro bono.”

SATURDAY morning comes, and there has been no letup in the storm. Overnight, however, Tribe has received an e-mail from two of his students, Anna Holloway LL.M ’07 and Daniel Gonen ’07, with some last-minute research, accomplished while they were grounded at Logan.

Despite the fact that his brief to the Court was filed weeks earlier, Tribe has continued to look for language from opinions that might lend additional support to his arguments. While waiting out the storm, Holloway and Gonen have found some encouraging parallels in several older cases to support the idea that the government cannot coerce a citizen into relinquishing a constitutionally protected right (a property right, no less, in a case dating back to 1926, Frost v. Railroad Commission).

Tribe sends them a reply. “Dan and Anna,” he writes, “The memo you attached is extremely useful, both in helping me to catalogue the cases and in furnishing some potentially helpful language for the sound-bite-sized observations to which a half-hour argument often requires resort.”

That last point is a reminder to himself as much as a thank-you to the students. Tribe tends to write and speak in long, wedding-cake paragraphs of cascading tiers, but on Monday he will have to keep things shorter and punchier, especially given the tendency of the justices to interrupt.

A few minutes before 6:00 a.m., he sends an e-mail to the rest of the team about the language in Frost. “I have good news,” he writes. “It’s a Supreme Court precedent, one I’ve written about in my treatise and mentioned a couple of times in our very first meeting in Cambridge but assumed that everybody had checked out and found wanting and thus never mentioned again. Well, thanks to the work that Dan and Anna did while stranded yesterday at Logan, the precedent has resurfaced. It’s a case in which the Supreme Court extracted from earlier decisions the broad principle that government may not ‘compel the surrender’ of ANY constitutional right ‘as a condition of its favor.’”

He continues: “I’d appreciate someone … letting me know some of the more notable cases that cite Frost approvingly, including any opinions by Scalia, Thomas, etc. … Does the Roberts opinion in the Solomon Amendment case do so?”

When asked if he is tailoring certain arguments to fit the known predilections of particular members of the Court, Tribe politely declines to answer in specific terms, citing “considerations of privilege and protocol.”

But more generally, he says: “Part of my preparation in any Supreme Court case involves reviewing the jurisprudence of each justice on the issues directly involved and on surrounding issues, and I try to craft an argument that can appeal to as wide a range of justices as possible, always taking care to stay within parameters determined by my sense of what can fairly be argued from the relevant texts and precedents. Sometimes I find it necessary to argue in the alternative, directing some arguments to part of the Court and others to another part of the Court, while being careful not to make arguments that directly or indirectly undercut or contradict one another.”

A meeting of the team has been called for 2:30 in Tribe’s suite. It will be the last one before Monday’s argument. Gonen and Holloway finally managed to get on a flight and have arrived. Kevin Russell, of the D.C. firm Howe & Russell, comes from his downtown office.

Budd-Falen and Stimpert are in town from Cheyenne and arrive with Frank Robbins and his wife, who wear matching jackets embroidered with the logo of the High Island Ranch. Robbins—easily six feet two inches in his boots and even taller in his Stetson—chews on a toothpick and banters with the others.

Tribe requests some last-minute research. He is focused on the government’s argument that the Fifth Amendment constrains only how the government itself may regulate, not the actions of individual officials. “I’d like to show that at least some of our cases about unconstitutional conditions or impermissible retaliation in fact involved actions by individual, perhaps even renegade, officials rather than actions by agencies or municipalities or counties or states or the federal government,” he says. “I’d appreciate having somebody dig ASAP to locate cases in which the anti-retaliation principle is enforced against individual government officials.”

The meeting breaks up after about an hour, and the students leave to chase down additional case law. Tribe goes back to studying at the Watergate, much the way he did in 2000, in the same hotel, when he prepared to argue Bush v. Gore. He spends the next day looking over cases and the student memos that come in by e-mail. Adding considerably to his stress, his voice has been failing, so he keeps a humidifier running.

MONDAY morning comes, and the storm has lifted. The white marble facades of the Supreme Court are dazzling. Inside, Frank Robbins is accompanied by a posse of supporters from Wyoming—most of them wearing Stetsons. Tribe, Russell and Budd-Falen sit at the table for the respondent’s counsel. The government is represented by Gregory Garre, a deputy solicitor general.

Garre goes first. From the outset, the justices’ questions indicate that they are primarily concerned with whether a Bivens action is an appropriate remedy for a violation of the Fifth Amendment right against retaliation claimed by Robbins. Garre implores the Court not to recognize “a new constitutional tort” that would extend Bivens “to an entirely new context” and “threaten public resources and public lands.”

Along with Justices Anthony Kennedy ’61 and Antonin Scalia ’60, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’56-’58 pushes to hear whether there were other channels—such as an injunction or an internal investigation—through which Robbins could have won relief from the officers’ pattern of misconduct. The justices sound skeptical that a Bivens action is the answer, but they sound equally unpersuaded that he could have pursued other avenues every time he was harassed. They raise the metaphor of death by a thousand cuts, aware that each separate filing of a grievance or complaint would have cost him more time and money.

Scalia shifts the focus, trying to clarify whether the BLM officers had simply been trying to negotiate new reciprocal easements after the ranch changed hands. Garre’s answer leaves the impression that they were.

Garre segues into the question of whether the BLM officers are immune from personal liability. They have immunity, he argues, because they were carrying out their official duties and could not possibly have known they were committing a constitutional tort.

Scalia interrupts: “Busting into his lodge? … They thought that was probably allowed?” Garre acknowledges that they might have known they were committing some kind of violation, but they couldn’t possibly have been on notice that they were committing a constitutional violation that has never been recognized.

When Tribe stands at the lectern to face the Court, his voice, though a bit gravelly, is strong enough to be heard. He begins with the immunity issue, saying that one needn’t have taken a special course in constitutional law to know that the deliberate decisions made over nearly 12 years to retaliate against Robbins were clearly forbidden.

Scalia dives in, still not clear about whether the BLM officers had merely been seeking to negotiate new reciprocal easements. If that was the case, he says, he’s inclined to tolerate some of their hardball tactics. (Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. ’79 suggests the same thing a bit later.) No, says Tribe, Robbins bought the ranch with a continuing right-of-way over government land for an access road, but the government didn’t have one over his ranch. Robbins’ right-of-way “ran with the land,” he says. “It was part of what he bought.”

That is, he adds, until the BLM canceled it. After that, Tribe notes, the officers continued to harass Robbins, trying to get him to “cough up” the easement. But instead of offering him one in return, they told him, “The United States does not negotiate.”

Justice Stephen Breyer ’64 is concerned that if the Court recognizes a Bivens cause of action in a property case, it will trigger a flood of federal lawsuits construing aggressive regulatory action as retaliatory. Tribe tries to allay the fear, citing cases in which the Court recognized a cause of action under Bivens for other violations by federal officers, and no flood of litigation ensued.

Justice Kennedy refers Tribe to a section of his brief and notes that some of the cited cases did not affirm the existence of a Bivens remedy for retaliation. But Tribe has never suggested that those cases support the existence of a Bivens remedy. He tries to set Kennedy straight, noting that he cited them for a different purpose—to refute the government’s statement that, prior to the 10th Circuit’s decision below, the right to be free from retaliation had been recognized only in cases involving punishment for exercising the right of free speech. Kennedy ends the discussion with “Let’s leave that aside,” but Tribe is clearly frustrated. The exchange has eaten up valuable time.

The chief justice comes back to the availability of other remedies: “Which of the government actions do you not have an existing remedy for?” Tribe answers, “It is the retaliatory pattern that there is no remedy for.”

Justice Samuel Alito asks about the RICO claim and is concerned by the dearth of precedent on whether public servants can be guilty of extortion when they extort a benefit for the government rather than for themselves. When Tribe starts to discuss one case, Willett v. Devoy, Roberts asks, “Are the BLM folks supposed to have known about Willett v. Devoy as clearly establishing their liability for what you call extortion [but] what they would call trying to save the taxpayers money and getting the type of reciprocal agreement with this landowner that they have got with thousands of others?”

The question gets Tribe’s dander up. “Well, Mr. Chief Justice, first of all, when you keep calling it a reciprocal agreement, it does trouble me,” he says. “They weren’t giving him anything. … They were trying to get the easement for nothing. … They were using the right-of-way, which was long gone, as an excuse to get an invaluable piece of property that they had no right to get. They were basically saying, and they made it explicit: Give us this easement for nothing or we’ll bury you.”

AFTERWARD on the plaza, Tribe stands in the bright sunlight with members of his team, but he is clearly distracted, perhaps replaying some of the argument. He never did point the Court to the language in Frost, not because there wasn’t time, but because he decided there were aspects of the case that were problematic. Overall, his sense is that, although Scalia, Kennedy, Ginsburg and David Souter ’66 seemed generally receptive to the argument that Robbins’ rights under the Just Compensation Clause had been violated—and perhaps clearly enough to get past the immunity hurdle—there aren’t five votes for the argument that what was done to Robbins was actionable in a Bivens suit.

He is also pessimistic about the RICO claim, because the justices sounded skeptical that the “predicate act” requirement can be met by an attempt to extort property for the government.

“All in all,” he concludes in an e-mail to a colleague the next day, “this portends a pretty high likelihood of a disappointing (but not surprising) outcome, though not one I felt I could really have done much if anything (either in the briefing or orally) to avoid, which prevents the experience itself from having been too dismaying.”

At least one other person awaits the Court’s decision with as much interest as Tribe does: Frank Robbins, now back in Wyoming, tending a herd of cattle that has dwindled from 8,000 to just 800 because he no longer has access to enough grazing land.

On June 25, as this issue of the Bulletin was going to press, the Supreme Court ruled 7-2 that Robbins could not proceed on his Bivens and RICO claims. The opinion, written by Justice Souter, can be found online here.