A child is jumping on a bed. His mother tells him to stop, and he asks the natural question: Why? Told it’s dangerous, the little boy has a follow-up: Why can I jump on some things and not on others?

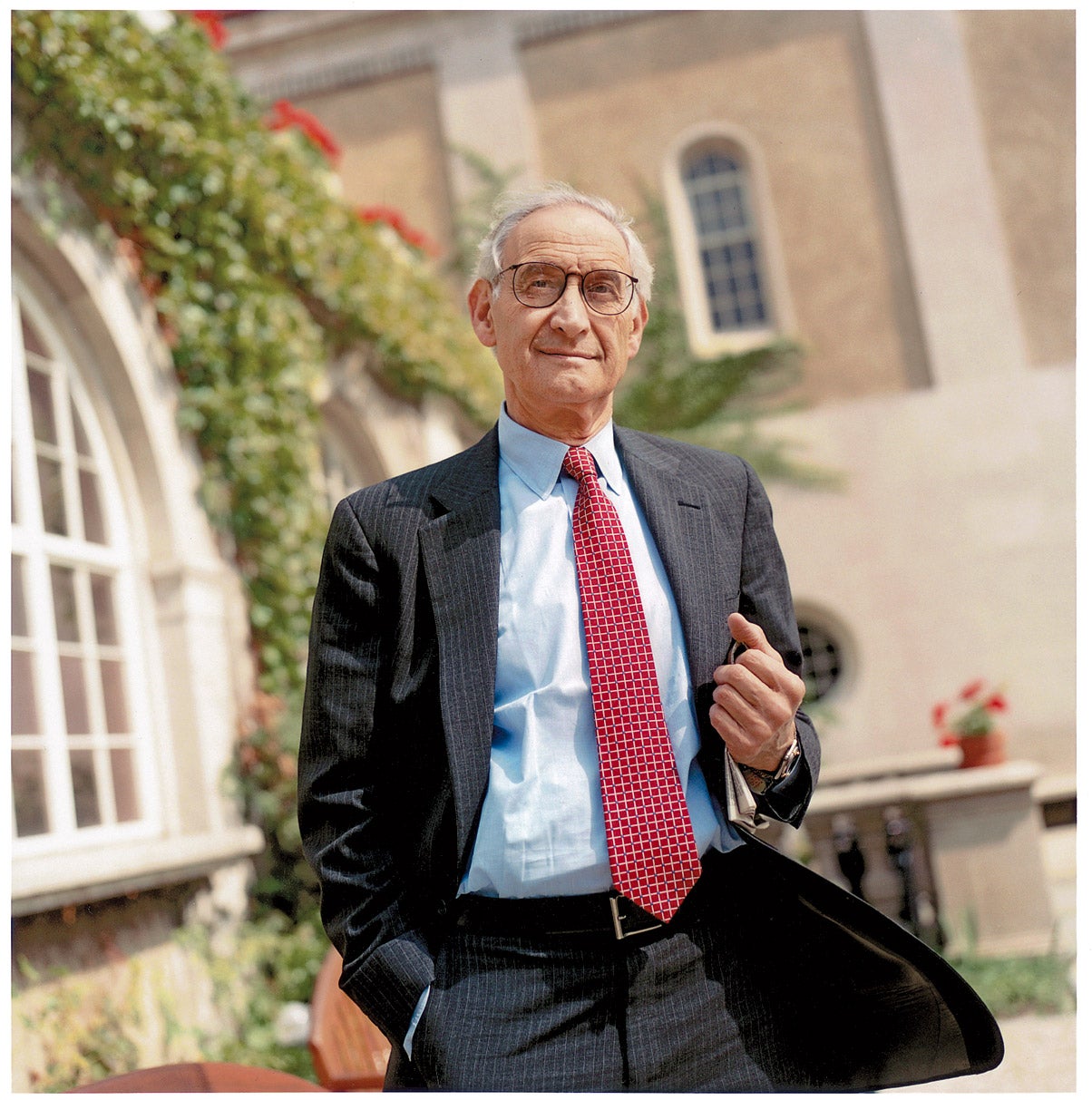

Children, according to Professor Charles Fried, are natural lawyers.

“They want to make distinctions, and they want to understand what’s behind the rule,” said Fried. “It’s an absolutely natural instinct in human beings. When told to do something, when told of a rule, they want to know exactly what it means and how far it extends.”

Adults have the same drive, and in the area of constitutional law, Fried is here to help them. In his latest book, “Saying What the Law Is: The Constitution in the Supreme Court” (Harvard University Press), he takes on federalism, separation of powers, free speech, religion and other thorny topics to explain the principles underlying rulings that often seem inconsistent.

“Essentially the idea is: Here are the subjects, which have a kind of coherence,” said Fried, former solicitor general of the United States. “Sometimes details escape the principles, and sometimes the details don’t hang together at all. But often they do, and when they do, I try to show that.”

By analyzing such recent decisions as the University of Michigan affirmative action cases and the Texas sodomy case, Fried wants readers to recognize the continuing relevance of constitutional law to their daily lives. But with so many law books out there–many unread–Fried was determined that his be reader-friendly. He worked to make every sentence free of legal jargon, so that educated laypeople as well as lawyers could enjoy it.

The clarity of his prose also reflects his conviction that “the subject matter is reasonable and what is reasonable is understandable and what is understandable has a certain simplicity.”

Free speech is one hot-button area he enjoyed tackling. “It’s a perfect example of my thesis about doctrine–that you can make sense of what the law is in terms of a principle, but the principle cuts deeper than the Court is willing to go,” he said. “In some respects, they get cold feet, and that’s inevitable.” Fried, by contrast, is a free-speech champion who even opposes defamation as a cause of action. He concedes that some restrictions are necessary in order to protect children but said censors use that as an excuse.

“Protecting adults who are offended by the fact [that potentially offensive material] is out there–give me a break!” he said. “All they have to do is turn the dial. A lot of the outcry against Howard Stern is just because he’s there, and someone is paying him to do this stuff, and they just don’t like it. That’s a really lousy reason for shutting somebody up.”

As for killing off libel and defamation, Fried says that, although the Court’s rulings point in that direction, he believes “the reason they haven’t gone that far is it would be too big a departure from existing law.”

While free speech and other issues often are so controversial that it isn’t easy for the Court to sort through them, tiptoeing through the thicket is its most important duty. “Rather than seizing a simple solution like outright prohibition or deciding to withdraw entirely from an area altogether, it’s important to try to develop doctrines which propel the principles into these difficult areas and take account of the differences without giving up the principles.”

“That’s not always possible,” he said, “but it’s what you should always try to do.”