Jeanne Charn ’70 was a restless law student. When she arrived at the Harvard Law School campus from the University of Michigan in the fall of 1967, the U.S. was riven by the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement, and, a few months later, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy. There was so much to be done, and Charn, who was born in the Midwest to Roosevelt Democrat parents, was eager to begin working to address some of the pressing social issues of the day.

Charn’s impatience with the abstract nature of traditional legal study and her drive to assist people at society’s margins would come to shape her life. The summer after her first year at Harvard Law, at the suggestion of Professor Frank E. A. Sander ’52, Charn became a student practitioner at the federally funded Community Legal Assistance Office. After graduating from law school, she served as a staff attorney and law student supervisor there before joining the Massachusetts Law Reform Institute as a staff attorney representing public housing organizations.

One day she got a call from a lawyer named Gary Bellow ’60, who needed help calculating rents under the federal Brooke Amendment, which capped rent in public housing projects at 25% of a tenant’s income. She was not previously familiar with Bellow’s work, although she later learned he was well-known in legal services circles. That call led to ongoing collaborations that sparked a lifelong partnership. She and Bellow eventually married and worked together until his death in 2000.

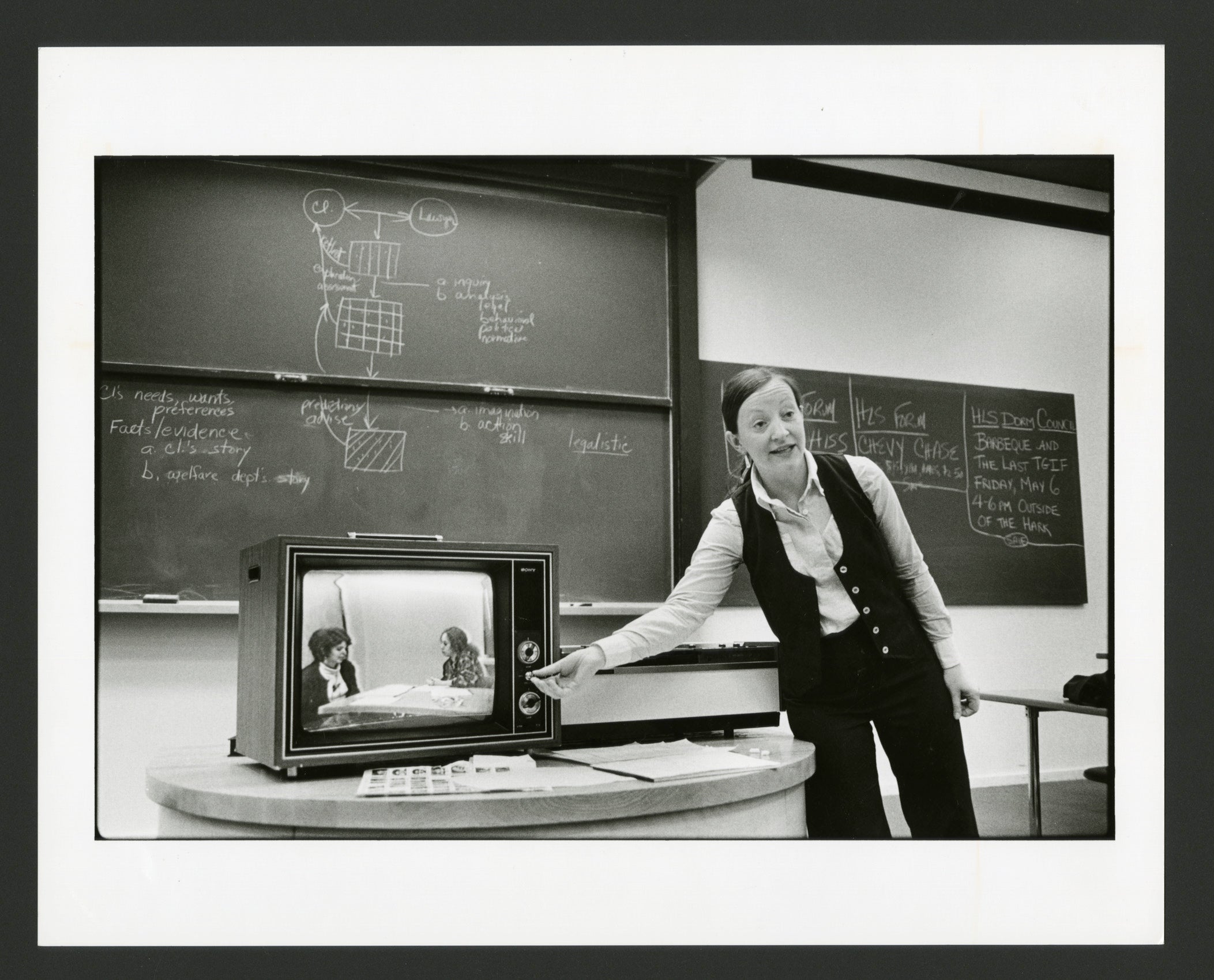

Charn played a central role in creating and developing what would become Harvard Law’s Clinical Program.

In 1979, Charn and Bellow successfully convinced Harvard Law School to support the creation of a legal services center in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston, to provide high-quality legal aid to urban communities, with law students involved in cases under the supervision of skilled attorneys working closely with the community. Eventually morphing into what is now called the WilmerHale Legal Services Center of Harvard Law School, or the LSC, “It was the first major law-school clinical program that had broad delivery of legal services at its core,” wrote Lincoln Caplan ’76 in a 2017 article in Harvard Magazine.

Unlike many of their peers, Charn and Bellow felt that direct services to people in need were as crucial as legislative efforts for long-term reform of the system. “Gary said it’s got to be service-based. A place in the community to be a place they can trust,” says Charn. Over the next decades, they supervised thousands of students, helped countless clients, and continued to shape conversations taking place about legal services and legal pedagogy.

Speaking at the Legal Services Center’s 40th-anniversary celebration in 2019, Sarah Boonin ’04, now associate dean for experiential learning and a clinical professor of law at Suffolk University, said the model was built on the idea that clinics should be immersed in the community they serve because “the community was also a teacher.”

Bellow and Charn’s efforts had a profound effect on the academic programs offered by law schools today. Nearly every law school in the country now has a clinical program. Harvard’s is the largest, with 25 in-house clinics and 13 externship clinics in a wide variety of practice areas; 89% of the J.D. Class of 2023 participated in at least one clinic, providing nearly 385,000 hours of pro bono legal assistance to those in need. Part of the broader HLS clinical program, the WilmerHale Legal Services Center serves more than 1,000 clients a year within six core areas: housing law, consumer protection, tax law, family law/domestic violence, LGBTQ+ advocacy, and veterans law/disability benefits.

Charn retired last summer after decades of service at HLS, having at different points in her career served as assistant dean for clinical programs; co-founder and director of the Legal Services Center; director of the Bellow-Sacks Access to Civil Legal Services Project, which leads research and policy initiatives to expand access to civil legal assistance for low- and moderate-income households; and senior lecturer on law, teaching courses and doing research on the legal profession and delivery of legal services. In 2014, she received the William Pincus Award for Outstanding Service and Commitment to Clinical Legal Education from the Association of American Law Schools, its highest award in the area of clinical education.

“Jeanne’s amazing legacy stretches in multiple directions,” says Daniel Nagin, faculty director of the LSC and the Veterans Legal Clinic. “She is one of the true giants in the history of clinical education — someone who has inspired not just generations of law students, but generations of clinicians entering the field. And she has never stopped innovating. Most recently, she has devoted her immense intellectual energy to advocating for new approaches to our yawning civil justice gap.”

Fresh out of law school at Northeastern in 1988, Liz Solar went to work as a lawyer in the housing unit at the Legal Services Center, where Charn, whom she describes as one of the best supervisors she ever had, taught her to put clients at the center of every case. “Jeanne was very client-centered and very patient and understanding of students’ perspectives,” says Solar, who for the past 18 years has been director of externships in the Harvard Law Office of Clinical and Pro Bono Programs. Moreover, Solar says, Charn and Bellow were very “purposeful in how they designed and built their staff,” bringing in people with a broad range of backgrounds and perspectives.

Charn was born in Indiana, where her grandparents had a dairy farm where she and her sister spent summers. Each evening her grandmother read them Eleanor Roosevelt’s newspaper column, “My Day,” from which Charn learned of the New Deal efforts to establish a social safety net for the poor and middle-class. “I was a little bit in awe of that era,” she says. “By the time I was in law school in the ’60s, we were hoping we could finish some of that.” She sighs and shakes her head. “But, man, we couldn’t,” she says, noting the work continues to this day.

Throughout their careers, Charn and Bellow were at the center of debates over how best to provide legal aid to low-income people and how law schools could participate in those efforts. Did their work change legal education? “We tried, for sure,” says Charn, who no doubt contributed to the important role experiential learning plays today.

She still laughs at the memory of that first phone call that started it all, a career and a life transformed, “all because I could calculate rent under the Brooke Amendment,” she says.