At the inaugural Belinda Sutton Distinguished Lecture, Johns Hopkins University Professor Martha S. Jones recounted her family’s historic and ongoing connections both to the institution of slavery and to several academic institutions, including Harvard. Jones, whose work examines how Black Americans have shaped the story of American democracy, leads her university’s Hard Histories at Hopkins Project, which works to uncover the role that racism and discrimination have played at the Baltimore-based institution.

The event at which Jones spoke honors Belinda Sutton, a woman who had been enslaved by Isaac Royall Jr., whose 1781 bequest to Harvard College funded a professorship that helped to establish Harvard Law in 1817. The annual lecture and conference series was established earlier this year at Harvard Law School and is organized by Guy-Uriel E. Charles, the Charles J. Ogletree Jr. Professor of Law and faculty director of the Charles Hamilton Institute for Race and Justice.

“Our school was founded in part through wealth generated through the profoundly immoral and evil institution of slavery,” Harvard Law School Dean John F. Manning said in his opening remarks. “Today, we gather to honor Belinda Sutton and other enslaved people by working to deepen our understanding of slavery and its legacy and to advance the ongoing pursuit of racial justice.”

Jones began her discussion by outlining work she leads to examine the challenging history of Johns Hopkins. “My talk today is about how I came to discover my own stake in our work on slavery in universities,” said Jones, the Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor, Professor of History, and Professor at the SNF Agora Institute. “It is about how I went from regarding the past as past to feeling it as very much present.”

Jones explained that her great, great grandmother, Susan, had been enslaved by Ormond Beatty, a professor and later president of Centre College in Danville, Kentucky. During the 20th century, Susie Jones, Susan’s granddaughter and Martha Jones’ grandmother, would tell Susan’s story to two researchers affiliated with Harvard.

The first of these encounters came in the 1920s, when Susie Jones was contacted by physical anthropologist Caroline Bond Day. Day, who earned a bachelor’s degree at Radcliffe College and a master’s at Harvard, used the techniques of physical anthropology, today discredited, to disprove false, but then-prevalent, pseudo-scientific theories about the inferiority of mixed-race people.

While researching her family history at Harvard’s Peabody Museum, where Day’s work is archived, Martha Jones discovered a letter Susie Jones had written the researcher.

“I needed to look no further than the handwriting to be sure that my grandmother was the author,” Martha Jones recalled, adding that the note was “filled with warmth from the salutation — ‘My Dear Carrie’ — to sign off — ‘Love to you. Yours, Susie.’ It includes moments of lightheartedness and gentle self-deprecation that frankly never appeared in her letters to me, which were most often filled with … advice about good study habits and such things.”

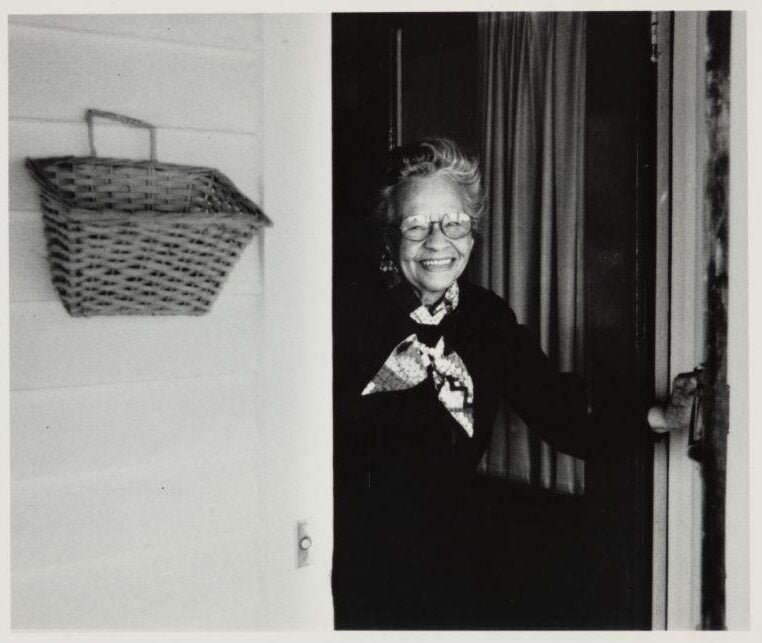

Credit: Provided by Harvard University

She also found samples of Susie’s hair, which Day had collected as part of her research, along with a handful of photographs. Seeing this tangible evidence — human remains — of her beloved grandmother’s life brought Martha Jones to tears. “And then that afternoon, I made [Susie’s] lock of hair the background image on my phone, just to make certain I wouldn’t forget it,” she recalled.

In the 1970s, Susie Jones would again become the focus of research being performed at Harvard when she agreed to speak to Merze Tate, an African American historian of diplomatic relations, for the Black Women Oral History Project at Radcliffe College. By then, Susie Jones had graduated from the University of Cincinnati, studied at Columbia University and the University of Chicago, had been married to the president of Bennett College, and had served for nearly a decade as that institution’s director of admissions. Both the audio and transcripts of her conversations with Tate are available on the Schlesinger Library website.

“I’m still puzzled by what it means to hear [Susie], who was by then herself the wife of a college president, telling Susan’s story,” Martha Jones said. “But there she is, the wife of a college president…recounting how her grandmother was once owned by another [college president].”

Looking back at her ancestors’ stories, Martha Jones confessed that her views about “how the histories of institutions and families collide in our study of slavery in the university” had changed. From her experiences delving into Johns Hopkins’ ties to slavery, she said, “I’d come to think about this problem as having three points of view: enslaved people and their descendants, enslavers and theirs, and then the researcher.”

Though “on most days,” she said, “I was decidedly the latter,” today Jones said she no longer thinks of herself that way. “I am instead also the descendant who cannot relegate Susan’s story, or [Susie’s] voice, and certainly not her lock of hair, simply to artifacts of some historical past. They are instead also present,” she said.

Jones noted the challenges of evaluating the complex narrative of her family’s history and the role of university researchers in that history. “After all,” she said, “it was a Black woman, a Black woman researcher, Caroline Bond Day, allied with the descendants of slaves, and the inheritors of slavery’s sexual violence. It was Day who collected [Susie’s] hair, and she could only do so because the two women were friends. They were intimates. They shared a bond of trust. Was Day an agent of [Susie’s] subjection…or weren’t they co-conspirators aiming for freedom?”

“They were I think, not unlike us, using the tools at hand to reconcile the past with the present,” she said. “They were, I am certain, looking to make another sort of future. They hoped to get more free.”

Years from now, when our grandchildren ask if we were “agents of our own subjection, or did we manage to somehow get more free,” Jones wants them to know that, like her ancestors, she “gently conspired to insert myself into Harvard’s archive to become part of its story of slavery in the university, to influence its direction.”

“Tell them when they ask about Belinda and Susan and [Susie], tell them about Caroline Bond Day and Merze Tate,” Jones concluded. “Tell them that, like these foremothers, I came here today so that, like these foremothers, …we all might get just a little more free.”