This March, as some of their classmates left Cambridge for warmer climates, ten Harvard Law School students trekked to arctic Alaska during spring break to help prepare tax returns for mostly low-income clients, primarily in indigenous communities.

Working in remote areas, they sometimes had no running water and slept on the floors of local schools or community buildings. Bush planes were often the only way in and out of isolated villages. The students put in 12-hour days since they might be the only tax preparers the residents would see all year. They were warned that they could endure unforeseen challenges: waiting outdoors on an airstrip at -20 degrees Fahrenheit due to a scheduling snafu, say, or surviving nearly a week without Internet service. And they were warned they might not make it back to campus before classes resumed if a blizzard prevented air travel.

For the most part, the trip went off without major hitches. And by the end of the week, the group — including Jon-Yin Mills Chong ’25, who launched the Alaska spring break project at Harvard Law School after having started it at Cornell as a graduate student — had filed approximately 500 tax returns which, in most cases, will result in tax refunds for their clients. Accurate and timely tax filings can have all kinds of legal implications for taxpayers, Chong notes, which is another reason they’re so important.

“There are a lot of things you can do with spring break besides working 12-hour days preparing tax returns in challenging conditions,” says Chong, “so it’s a big commitment but it’s also incredibly rewarding.” In addition to providing direct services to people who need them, “you are seeing places you would never, ever get to see without providing this service.”

“It was so gratifying to tell folks, ‘You’re going to get X dollars back,’” says Anne DeLong ’24, who spent several days in a small city in the Central Yup’ik area working directly with indigenous taxpayers, then several more in Anchorage, where she prepared returns mailed in from remote areas. DeLong notes, that while the eviction defense work she does at the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau can result in victories, they often take more time. “It’s so great to see the work you do will have an immediate positive impact on someone’s life or their family’s life.”

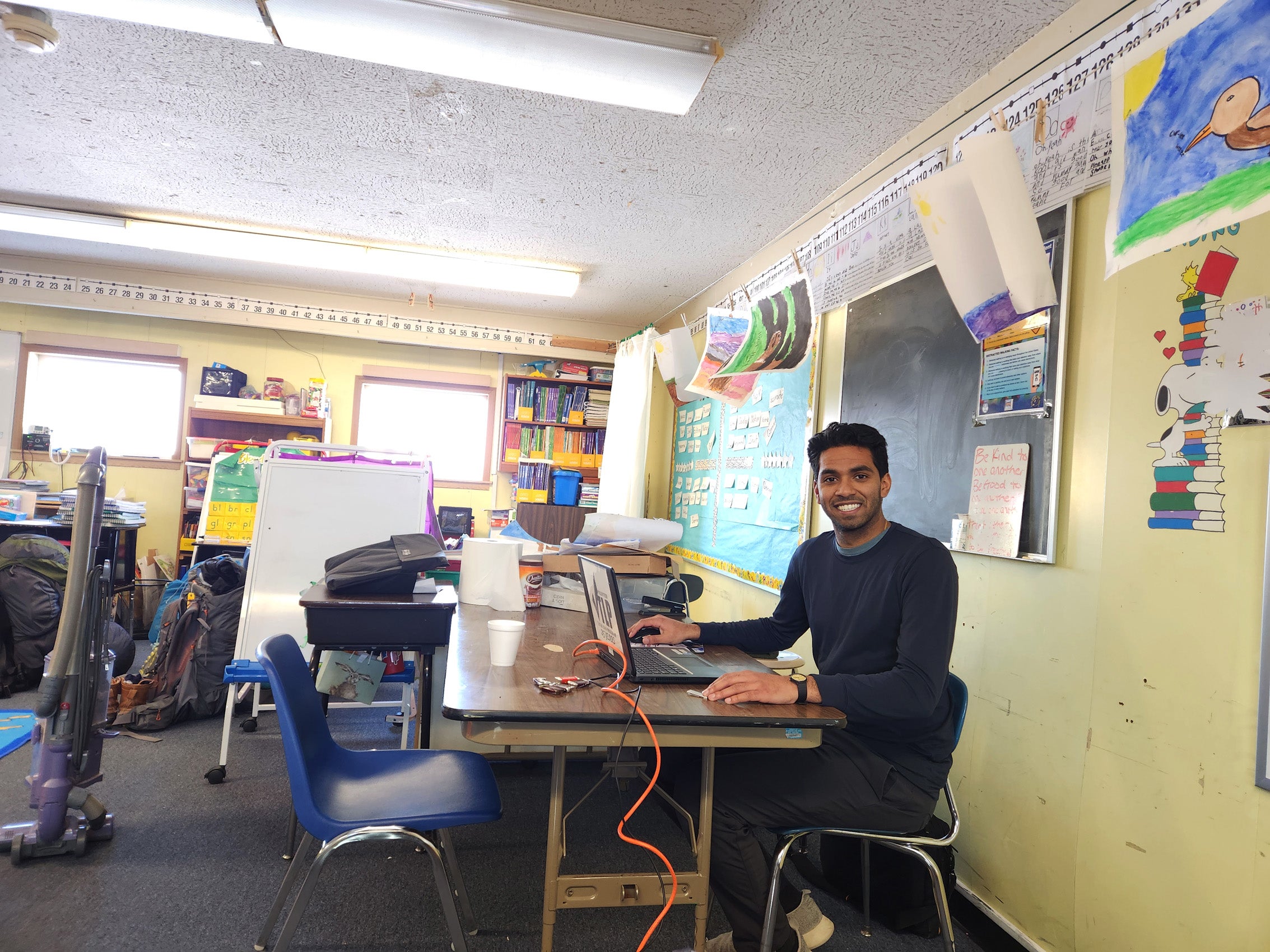

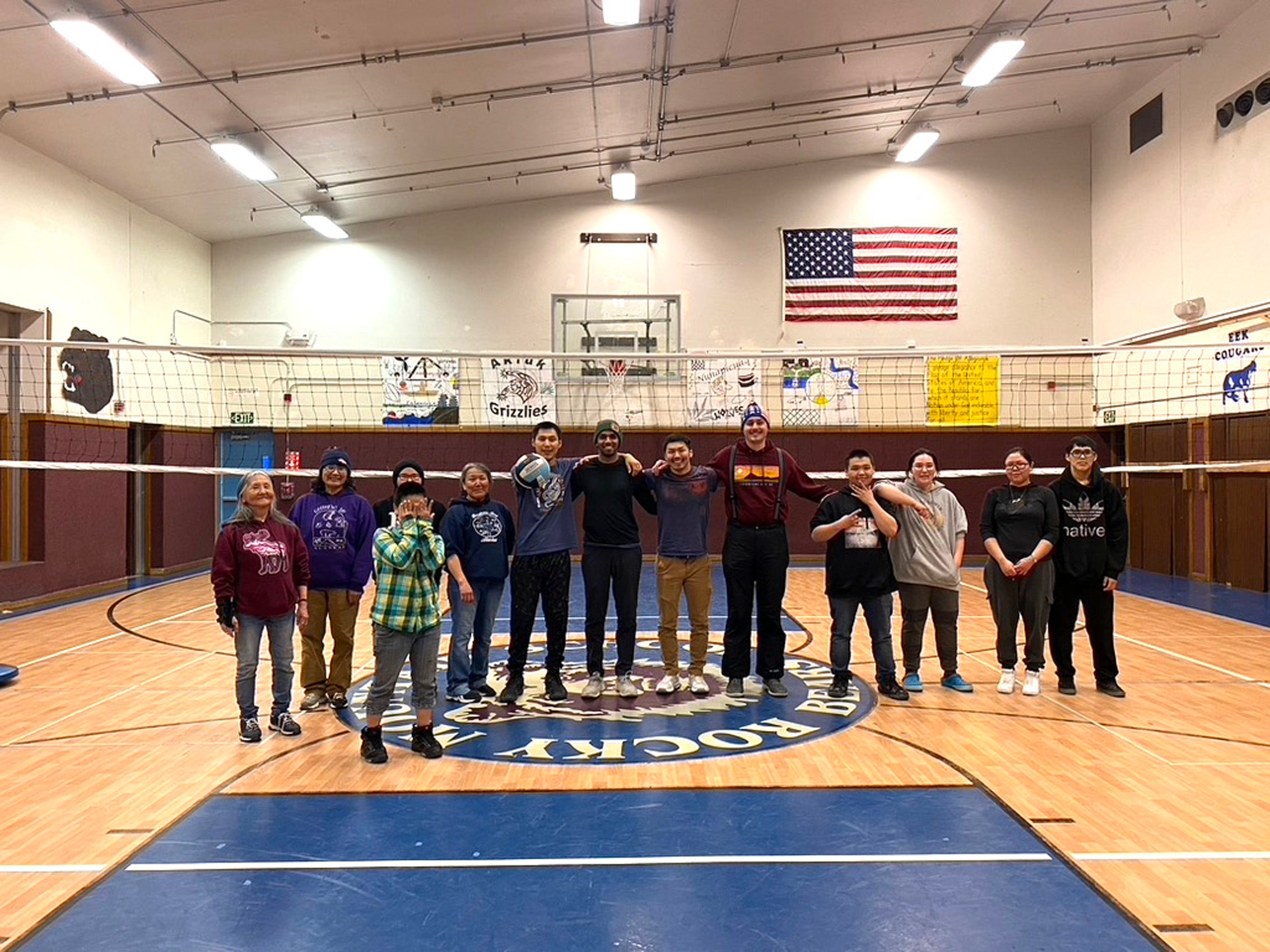

Unlike many on the team, Kristi L. Tanaka ’24 had been to Alaska, where she was stationed for three years after graduating from the U.S. Air Force Academy in 2015. But she was based in Anchorage and never saw less-accessible parts of the state, which is one reason she signed up for the spring break project. Tanaka spent part of her week in a village of about 60 people, where there were no restaurants or public spaces, along with a team leader from the Alaska Business Development Center, which runs the tax project, and two other Harvard Law students, Monty Barker ’25 and Anand Balaji ’24.

They arrived to find that both heat and water were not available in the village. Because there are so few visitors, everyone heard the prop plane approaching and several people — as well as the village dogs — came to the gravel airstrip to greet them, Tanaka recalls. “You get a real sense of how off the grid you are,” says Tanaka, who slept at the village school, which had heat and water reserves. “It was negative 10 [degrees] with an extremely strong, unrelenting wind. I’d never felt such cold on my face even though I lived in Alaska … everything that comes off the Bering Sea kind of hits you.” The economy of the village is what is considered partial subsistence, with people living partially off the land; one taxpayer Tanaka worked with is involved in whale hunting, while others worked in construction.

The spring break project was under the auspices of the Alaska Business Development Center, which for over 25 years has offered tax assistance directly to communities through its Volunteer Tax and Loan Program. Due to such factors as geographic isolation and structural barriers to technology, indigenous communities typically have limited access to free federally funded tax preparation programs that are widely available in the lower 48 states, such as the IRS’s Volunteer Income Tax Assistance program. Almost all the communities the ABDC serves are majority indigenous, and in 2022, its volunteers prepared about 5,200 tax returns, generating $13.3 million for rural communities.

Chong, who holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees with concentrations in accounting, helped launch the VTLP program in 2018 at Cornell, where it is still going strong, and he traveled to Alaska himself that year to do returns. After Cornell, he worked as a paralegal and accountant at the Federal Tax Clinic at the Harvard Law School’s WilmerHale Legal Services Center, which included preparing tax returns for low-income people out of the trunk of his car during the pandemic. In 2021, he started a program to help survivors of domestic violence get tax credits and pandemic stimulus funds that their abusers wrongfully took.

In spring 2022, Chong, two fellow students, and one clinical instructor took a self-funded trip to work with Alaska Business Development Center’s volunteer tax and loan program. Since villages were not taking in outsiders during the pandemic, they spent the week in Anchorage preparing over 150 returns. This year, Chong decided to expand the Harvard Law presence into a spring break project.

For partners, he reached out to the Harvard Native American Law Students Association, and to Harvard TaxHelp, a student organization through which students provide free tax preparation services to low-income clients in Cambridge, Massachusetts. TaxHelp’s Co-President Nathan Bartholomew ’24, a certified public accountant, is among the students who went on the Alaska spring break project. The law school’s Office of Clinical and Pro Bono Programs paid for roundtrip tickets, while Alaska’s tax prep program covered the cost of lodging and travel.

“It’s so great to see the work you do will have an immediate positive impact on someone’s life or their family’s life.”

Anne DeLong ’24

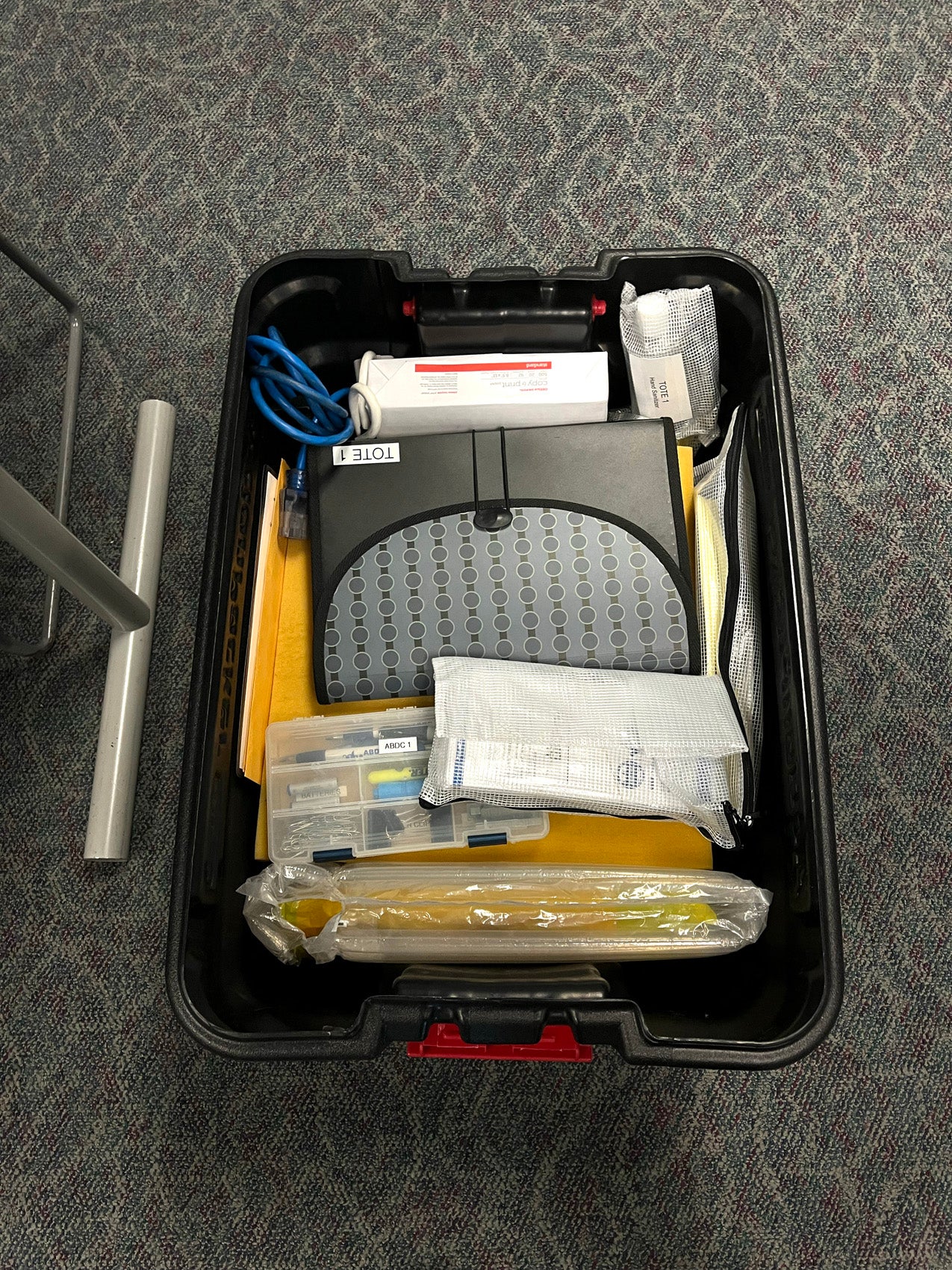

Before the trip, many of the students had little experience doing tax returns besides their own, but ABDC put them through more than 40 hours of rigorous training. Low-income returns in Alaska are typically more complex than those in the lower 48 states due to the high prevalence of multigenerational households and self-employment, as well as unique tax benefits for which indigenous populations and Alaskan residents may be eligible. Alaska has special permission from the IRS to prepare returns that are out-of-scope for VITA and other IRS programs. In addition to achieving Advanced VITA certification through the IRS, the students did Alaska-specific training and completed at least 14 Alaska-specific practice returns.

“The Alaska Business Development Center needs you to be really good before you step foot on Alaska soil, so you’re not only doing 14 tax returns but six quizzes and other exercises,” says Chong, who also worked one-on-one with students to train them. And, since the tax program relies on these volunteers, they must be committed no matter what arises. “In some cases, if you back out at the last minute, there’s literally no one to replace you,” Chong says. “The people who were on this trip were all excellent and did really high-quality work.”

Tanaka, he notes, brought colorful stickers and sweets for the children of the taxpayers they worked with, and DeLong brought oranges since it’s hard to get fresh produce, especially in the winter. “It’s little things like that that mean so much,” says Chong. DeLong was one of three students on the trip who identify as having indigenous heritage, Chong notes, adding, “I’m not indigenous but the people we’re serving are. I think representation is incredibly important, where people in the communities can see there are indigenous students at HLS who are helping them.”

“I felt like I was so well-prepared going into these communities because we had done practice returns that were more advanced than the things I saw in the field, and everyone at Alaska Business Development Center was accessible by phone when we inevitably had questions,” says DeLong. “I walked away from this deciding I’ll take tax law next year.”

Both DeLong and Tanaka found the project so fulfilling that they are continuing to prepare low-income tax returns in Cambridge with TaxHelp, and say they are interested to see how filing Massachusetts taxes is different from the ones they did in Alaska.

DeLong, a member of the Osage Nation who grew up in Oklahoma, says, “It was remarkable to see so many folks of all different ages speaking their native languages so fluently with each other. In my tribe, only a handful of elders speak Osage fluently.” Another benefit of the trip, she says, is that the Harvard Law group comprised a very “diverse and interesting mix of students,” many of whom she hadn’t interacted with before.

“It challenges you in a lot of different ways, which will help you be a better advocate, lawyer, community organizer,” she says. “There are not a lot of instances where you can enter someone’s community as a complete newcomer and help them with these services, so it’s really valuable in that way.”

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.