Last month, the Department of Veterans Affairs ended a marriage duration requirement that largely excluded surviving partners of LGBTQ+ veterans. This decision, which will potentially expand benefits to thousands of survivors, followed efforts over the past two years by Harvard Law School students in the Veterans Legal Clinic at the WilmerHale Legal Services Center.

During 2020, the clinic took up the case of Miami Beach resident Lawrence Vilord whose spouse — a Vietnam War veteran — passed away in June of that year. The couple had been together 44 years. For much of that time, Vilord served as caregiver to his partner, who was rendered quadriplegic after a household fall resulting from his combat injuries.

But the VA told Vilord that he wasn’t eligible for the enhanced Dependent and Indemnity Compensation for surviving spouses of disabled vets, because they hadn’t been married for at least eight years. This rule effectively disqualified all same-sex couples in nearly every state, as the U.S. Supreme Court only declared restrictions on same-sex marriages unconstitutional in their 2015 ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges.

Arguing that the ongoing time requirement was unconstitutional for several reasons, the clinic initially filed two separate briefs with the Board of Veterans Appeals and Court of Appeals for Veteran Claims — the first focusing mainly on the specific Vilord case, the second on the broader policy issues. Both were considered by the VA in deciding last month to reverse its policy.

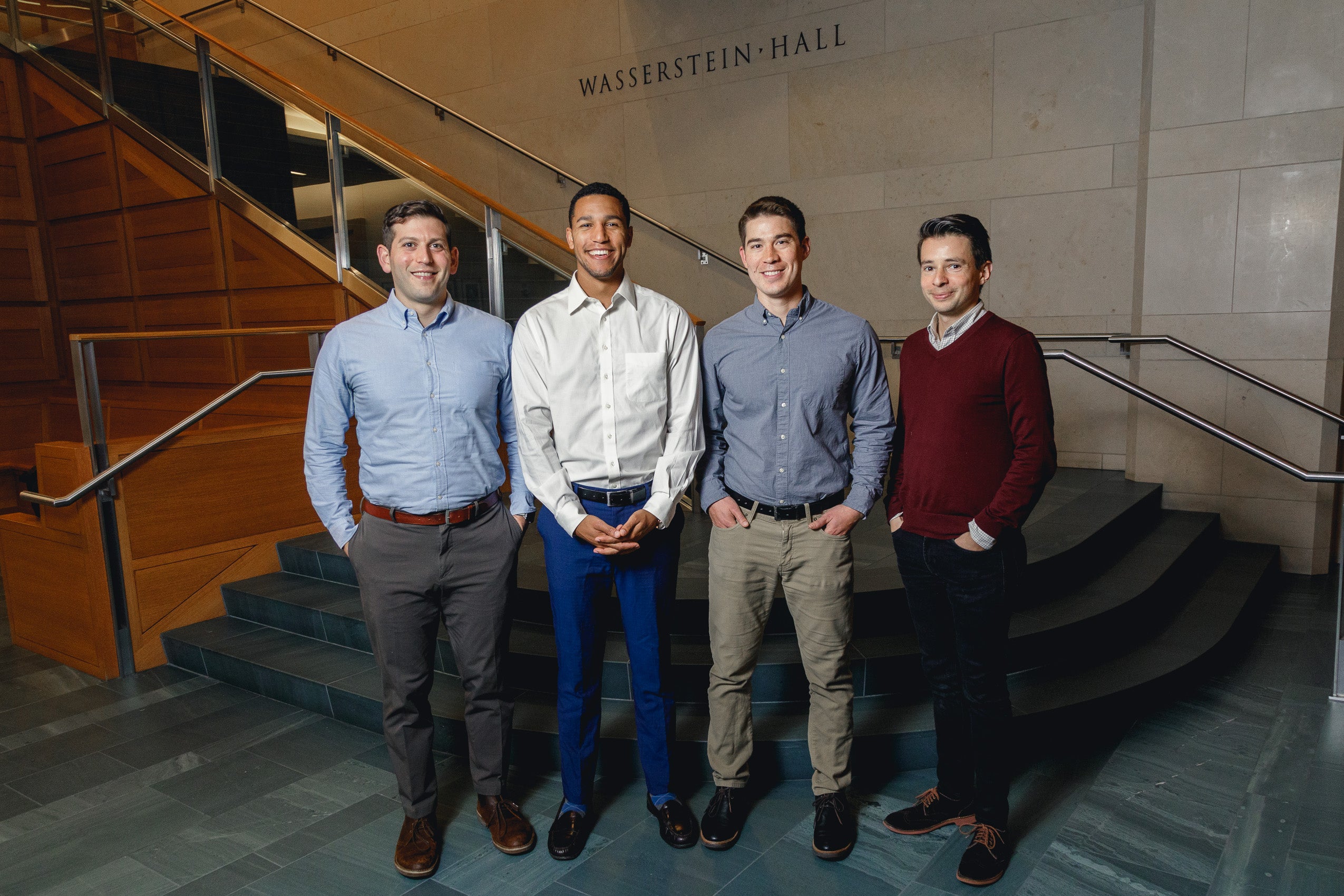

“We tried to have it both ways. We argued that if anyone should get relief, it should be our client,” says Noah Sissoko ’23, who worked on the first brief with Tyler Patrick ’22. “But also, [the time requirement] does violate due process and equal protection of the law, and the stated goals that the VA has for protecting widows. We basically tried to throw all of it into the brief and see what stuck.

“We thought we had a great client, and Mr. Vilord gave us a lot of leeway to figure out what we thought was best,” Sissoko says. “But I think it’s incredible [that] we actually did, as a bunch of law students, change VA policy. That’s one of the proudest things I can say I’ve done, not only in law school but in life up to this point. A bunch of 20-somethings came together and we changed policy for veterans, who are the most deserving people in our society.”

“This is going to mean access to benefits upon death for thousands of LBGTQ+ families, if not tens of thousands, that will make a huge difference in peoples’ lives.”

David Paul ’24

“This is going to mean access to benefits upon death for thousands of LBGTQ+ families, if not tens of thousands, that will make a huge difference in peoples’ lives,” says David Paul ’24, who was a member of the Veteran Clinic team representing Vilord this year. “Taking care of a disabled person is both emotionally and financially very taxing. And very often in those cases, the surviving partner didn’t have the opportunity to work or save money. That’s what these benefits were designed to help with, and now those survivors will have benefits.”

“The student teams who worked on Mr. Vilord’s case over these last five semesters all have modeled excellence in clinical lawyering,” said Clinical Professor Daniel Nagin, faculty director of the WilmerHale Legal Services Center and Veterans Legal Clinic. “They have brought passion, grit, and creativity. They have been client-centered throughout. They have demonstrated superb lawyering skills and instincts. And, consistent with the principles of clinical legal education, they have eagerly embraced the responsibility that comes with being the lead advocates on the case. They have made every strategic judgment, executed on every plan, and then thoughtfully revisited their strategy every time circumstances required — which was often, given the novel constitutional claims they were pursuing.”

Vilord himself expressed his gratitude in a recent email. “I know that Rhett [his late husband] would have backed me every step of the way on this journey. Because of him, and because we believed in each other’s well-being, to do the right thing to try to help other people, I am honored that a wrong has been made right for many others. That has been a part of this journey, understanding what I was trying to accomplish and hopefully help others accomplish something that has long been denied to many people for years.”

For the students in the clinic, the case provided especially valuable lesson in legal strategy.

“The law is an important tool and you have to litigate cases and argue issues,” said Ben Waldman ’23, himself a veteran. “But I learned that thinking strategically and thinking like a lawyer is much more than that. We thought about every button we could push to advocate for our client, and the pros and cons of each one. We talked that over with the clinical faculty with great insight.

Last semester was a great example,” he said, “because the posture of the case was that we were not litigating the underlying constitutional questions. Instead we were thinking strategically about how to get this case before a decision maker who has the power to vindicate our client’s constitutional rights. And that often meant not appealing something that you reflexively might want to. So, that involved a little counter-intuitive thinking, about multiple variables and options.”

Nathan Lowry ’24 agrees that the experience provided him a perspective he wouldn’t have gotten from the classroom alone. “Coming into 1L, things seem very ethereal and you don’t really know what litigation really entails. Coming into law school, I wasn’t sure what I necessarily wanted to do after this. But to see the actual impact you can have, and the effect you can have in getting benefits for people who deserve them and were wrongfully treated: that was really eye-opening for me.”

“I think it’s incredible — We actually did, as a bunch of law students, change VA policy. That’s one of the proudest things I can say I’ve done.”

Noah Sissoko ’23

As a Marine Corps veteran who served in Afghanistan, Lowry had previously negotiated with the VA in a different context. “As a combat veteran, I was entitled to five years of health care upon returning, and it was such a frustration navigating that myriad of systems. I worked for a full year to get the healthcare I was legally owed. I think this clinic gave me a great opportunity to give back to veterans who might be in similar situations.”

“As a combat veteran, I was entitled to five years of health care upon returning, and it was such a frustration navigating that myriad of systems. … I think this clinic gave me a great opportunity to give back to veterans who might be in similar situations.”

Nathan Lowry ’24

Adds Paul, “We had a strong framework from our first-year doctrinal classes, constitutional law being the big one here. But we had very little experience in how to manage the procedural intricacies of the veterans’ legal system. Learning from our [faculty] supervisors who were experts in this very niche field, who could tell us what to look for in the law, and who could also give us pointers about the attorneys we’d be talking to. That has been invaluable, and a big part of why we were able to prod things along in whatever way we did.”

But some key questions remain to be litigated. Among them: The VA is now requiring that qualifying couples demonstrate that they maintained “marriage-like” relationships for the eight years — a term the students say is both hard to define and also hard to prove when relationships were necessarily kept secret under the government’s previous “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy.