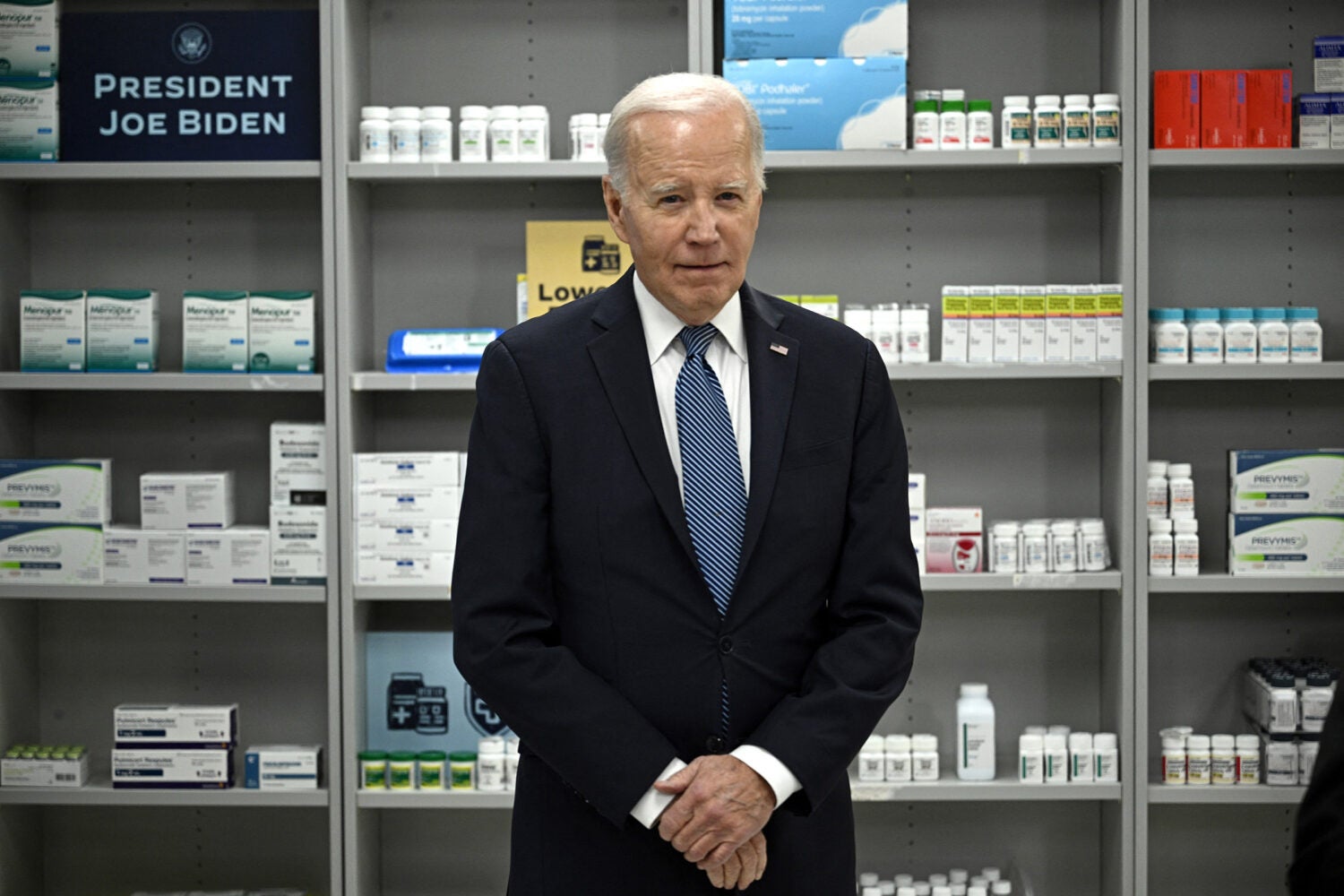

The Biden administration is once again targeting high drug prices paid by Americans. This time, officials are focused on prescription medications developed with federal tax dollars. The United States government, through the National Institutes of Health (NIH), awards billions of dollars of research grants to university scientists each year to fund biomedical research, which is often patented. The universities in turn grant exclusive licenses to companies to produce and sell the resulting drugs to patients in need. But what happens if a drug company fails to make a medication available, or sets its price so high that it is out of reach for a significant percentage of patients?

To tackle this problem, the Biden administration recently released a “proposed framework” that specifies when and how the NIH can “march in” and award the rights to produce a patented drug to a third party if the patent licensee does not make it available to the public on “reasonable terms.” The plan is based on a provision included in the Bayh-Dole Act, a 1980 federal law which was designed to stimulate innovation by encouraging universities to obtain and license patents for inventions resulting from federally funded research.

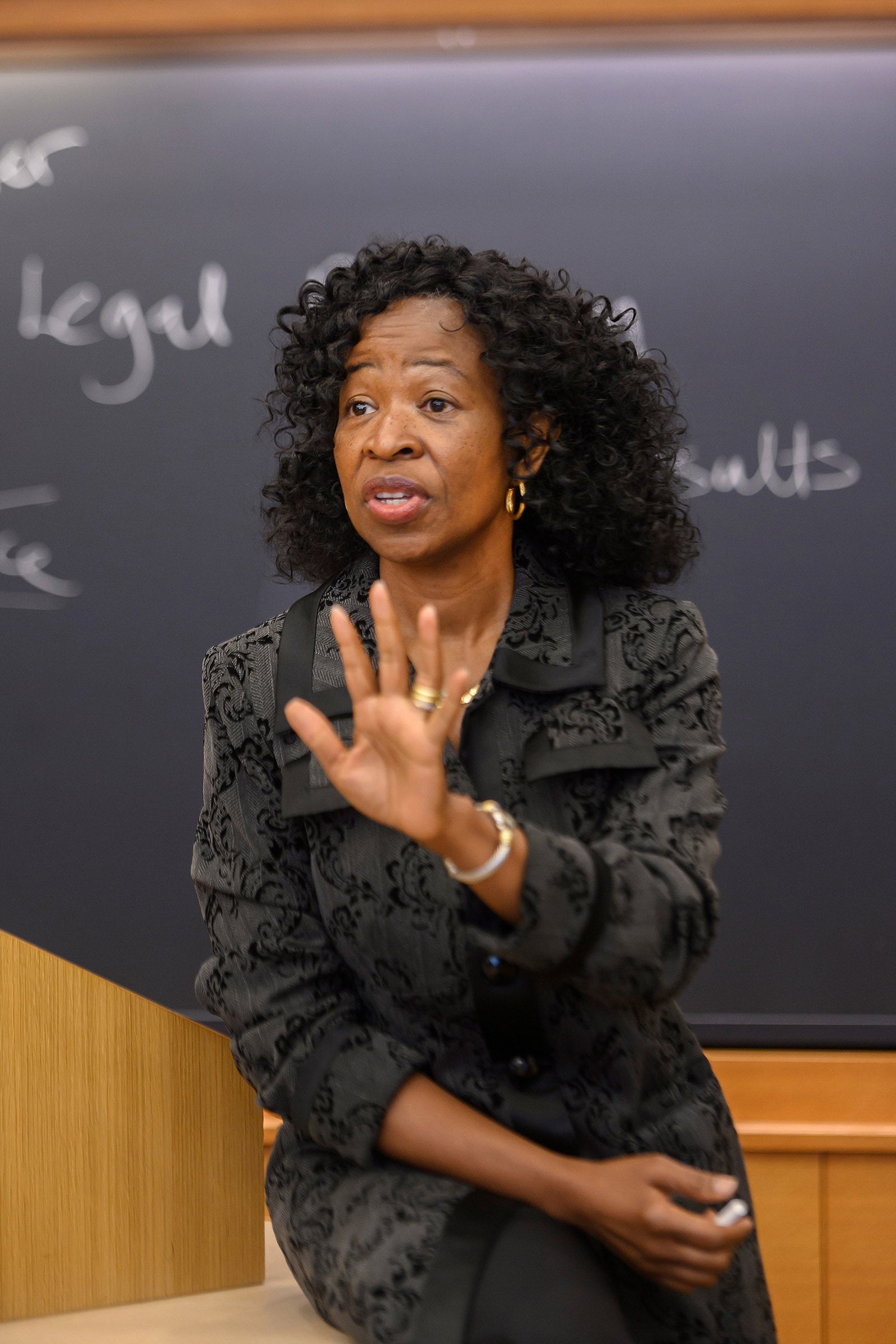

According to Harvard Law School intellectual property expert Ruth Okediji LL.M. ’91, S.J.D. ’96, although the Biden administration’s proposed framework for using government march-in rights to lower drug costs is an important development, whether it will be successfully implemented and result in meaningful drug price reductions remains to be seen. Harvard Law Today recently spoke to Okediji, the Jeremiah Smith, Jr. Professor of Law and faculty director of Global Access in Action (GAiA) at the Berkman Klein Center, about the new proposal and the legal challenges it might face.

Harvard Law Today: What is your first impression of the Biden administration’s proposal to use march-in rights to lower drug costs?

Ruth Okediji: I think it is a step in the right direction, by which I mean it is an acknowledgement that we have a system that currently makes many vital drugs, including drugs funded with federal taxpayer money, inaccessible to many Americans. The administration’s proposal to use march-in rights is a move that I certainly welcome, given my scholarly focus on strengthening the government’s role in improving access to medicines generally. The fact is the government is not powerless — there are ethical, moral, and economic justifications for greater involvement nationally and globally. A substantial proportion of drug research and development is funded or subsidized by the federal government, whether you’re talking about COVID-19 vaccines, insulin for diabetes, or other prescription drugs. For much of our history, individual patients have been fighting this problem alone, and often unsuccessfully. Millions of patients in the U.S. have been unable to access essential drugs because they couldn’t afford them, including people of color, single moms, elderly citizens, and the most impoverished Americans in rural communities. The Biden administration is clearly signaling its concern about drug prices, and their impact on the quality of life for American patients and their families. Whether the administration’s draft proposal is in fact implemented and leads to measurable improvements in drug accessibility is a completely different story.

HLT: What are march-in rights?

Okediji: March-in rights originate in the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980. This is a federal law that allowed academic research institutions to take title to patented inventions developed using NIH or other federal funding, and to grant exclusive licenses to private companies to bring the products incorporating those inventions to the market. The Bayh-Dole Act states that if an invention is not being commercialized or is otherwise inaccessible to the public, the government can ‘march in’ and make the patent holder license the invention to other companies. A patent is a quasi-monopoly and march-in rights basically break up that monopoly, meaning that more than one company can produce the patented drug without the patent holder’s permission.

HLT: Has anyone tried to use the government’s march-in rights before?

There have been petitions by consumer and patient rights groups to the NIH for years, arguing that the NIH should exercise its powers pursuant to the Bayh-Dole Act, to make high-priced drugs more accessible to patients. For instance, multiple petitions focused on the prostate cancer drug Xtandi, whose cost in the U.S. — $160,000 per year — is at least five times higher than in Canada and Japan. There have also been petitions over the HIV drug Norvir and Xalatan eye drops for glaucoma. All these petitions were, however, rejected by the NIH based on a finding that the medications in question were “reasonably available” to patients in accordance with a standard set forth in the Bayh-Dole Act. This is a long-standing, open sore in the American healthcare landscape. And this new move by the Biden administration, I think, is a good signal that the pain so many Americans needlessly endure is gaining attention. Again, I’m not sure that an actual march-in scenario will happen, but this nod by the Biden administration to the serious challenge of access to medicines may contribute to the eventual resolution of a long-standing national problem.

“This nod by the Biden administration to the serious challenge of access to medicines may contribute to the eventual resolution of a long-standing national problem.”

HLT: Why has it never happened before, and why might it not happen now that the administration published the framework?

Okediji: The text of the proposed framework sets the bar for granting march-in rights very high. It requires that the drug price be “extreme” and “unjustified.” As lawyers, we know the open-endedness of terms and that, when the bar is set that high, it’s hard to see how the agency can satisfy the criteria for exercising march-in rights. Depending on its application, the standard of “reasonableness” of prices could lead to no meaningful changes in drug accessibility, or it could make a real difference for average Americans. The Biden administration could have used foreign prices for drugs, which are often lower, as a reference point, but it didn’t. And so, it’s not clear that the framework is going to make a difference immediately or at all. It will depend on both its application and the way the NIH thinks about the standards that have been set forth in the framework.

HLT: Why do you think the administration did not set a lower bar for exerting march-in rights or use foreign drug prices as a benchmark?

Okediji: There has always been an argument, and you can see this in the reactions to the Biden administration’s proposal, that the exercise of march-in rights will destroy innovation and undermine the very purposes for which the Bayh-Dole Act was enacted. The view that anything that interferes with the patent holders’ interests impedes innovation is a stronghold in global policy debates over access to medicines, and it resonates powerfully with our distinctive preference for market solutions even in the face of tremendous human suffering. The word “innovation” is waved about by the industry like a talisman, and it unfortunately obscures considerations of fairness, human dignity, and exploration of serious alternatives to the existing political choices. The text of the proposed framework clearly suggests that the Biden administration is not immune to claims that march-in rights could have a chilling effect on innovation. But the very idea that the price of innovation is the lives of Americans who cannot afford drugs should trouble all of us. There is ample scholarly exploration of policy options that promote pharmaceutical innovation and control the prices of drugs without sacrificing the health and wellbeing of Americans, more so when our tax dollars contributed meaningfully to the R&D. We must resist the not-so-implicit hypothesis that pharmaceutical innovation requires us to sacrifice our commitment to the common good.

“The very idea that the price of innovation is the lives of Americans who cannot afford drugs should trouble all of us.”

HLT: In setting the bar so high, do you think administration officials are trying to insulate NIH from future litigation if and when it does exercise march-in rights?

Okediji: To be clear, march-in rights are a form of compulsory licensing, because the government essentially issues a license to others to manufacture the drug. Every government has this right, whether stated in its patent law or grounded in some other regime. Since its inception in 1883, the international patent system has recognized a government’s right to intervene in the market for the patented product to protect the public interest. Sometimes, and certainly in the global setting, the main point of establishing a compulsory licensing scheme is for governments to obtain leverage to negotiate lower drug prices. That prospect in and of itself is a potential benefit of the proposed new framework for the exercise of march-in rights. If there are patent-owning firms that are willing to negotiate prices due to a threat of march-in rights, then that helps to address the problem of high prices without costly litigation. As I’ve mentioned, there are other policy levers such as voluntary licensing, tiered pricing, patent law adjustments, and regulatory reform that I and other scholars including Terry Fisher [’82], Margo Bagley, and Aaron Kesselheim have highlighted in our research. The cost of drugs is a threat to the sustainable welfare of any country. The fact that other countries have found effective ways of controlling drug prices that we are not yet seriously considering in the U.S. is a moral challenge to us. The government must have an array of tools to exercise its public duty to ensure the well-being of Americans’ health — and it must be willing to prudently deploy those tools as needed.

“The cost of drugs is a threat to the sustainable welfare of any country.”

HLT: Most of the federally funded drug research is conducted by scientists at universities. Will this proposal have any implications for them?

Okediji: Yes, we certainly saw this during the HIV/AIDS crisis when student groups, together with faculty, advocated for universities to adopt policies to make their patented HIV/AIDS drugs available globally at lower prices. But the level of control individual faculty members can exert over the pricing of a drug they helped develop usually significantly diminishes once the drug is licensed. Under most university schemes, the faculty member invents a new drug and then, under the university’s intellectual property policy, there is a sharing formula that allocates financial returns to the professor, her or his academic department, and the university once the university enters a technology commercialization deal with a company that develops the drug and brings it to market. In this standard scenario, the relationship between the inventor and the firm that commercializes the drug becomes quite attenuated. But I still think it is worthwhile — from an ethical standpoint — for scientists to demand that their research programs make drugs available at lower prices to those who cannot afford to pay the market price.

As an example from the copyright side of things, not too long ago, my co-authors and I negotiated with our publisher to publish a cheaper, paperback version of our leading copyright casebook. Today, students can choose between a fancy version of the book with bells and whistles added by the publisher, and a basic version that’s much cheaper. My co-authors and I felt strongly that we could not be silent in the face of the extraordinarily high price tag of the casebook. So, we used our leverage as authors to do something about it. It’s a small example and there are obviously many nuances, but I do think there is more that we can do as academic inventors and authors to facilitate access to our creative works for the public interest.

Larry Lessig’s launch of Creative Commons licenses right here at the Berkman Klein Center more than two decades ago occasioned a revolution in sharing access to scientific and literary works that is still ongoing today. The scale of sharing enabled by these licenses was unimaginable under then-orthodox views of the copyright system, and that transformative sharing has unlocked a wealth of global knowledge. The same can be done for access to drugs, without which many simply cannot live well or live at all. We must be willing to challenge economic arrangements cloaked in intellectual property garb that require us to abandon fair and useful options to make drugs accessible for the improved wellbeing of Americans. This is, after all, the main point of the intellectual property system — the advancement of human welfare.

HLT: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Okediji: There’s the fundamental question of whether Americans should be paying the highest drug prices in the world, and whether there really must be a tradeoff between innovation and accessibility of essential medicines. It is hard to make adjustments without a clear vision for what we are ultimately trying to accomplish with drug prices and our healthcare system overall. There must be a change in our perception of what is right for the American consumer, the American patient. This proposed framework by the Biden administration is one step. It is an important signal. But it is by no means the end of the story. And it is by no means a silver bullet.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.