Credit: Asia Kepka Janet Halley criticizes feminists for relying mainly on a “prohibitionist” approach that identifies what’s bad in the world and then writes a statute making it unlawful.

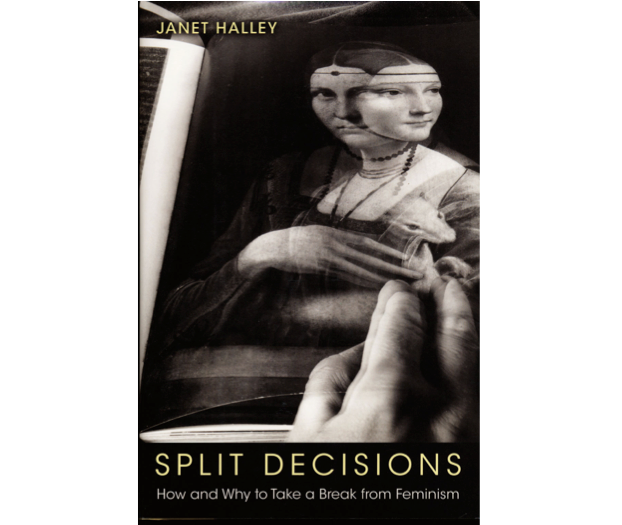

Janet Halley spent six years writing “Split Decisions: How and Why to Take a Break from Feminism” (Princeton University Press, 2006), a groundbreaking book examining the contradictions and limitations of feminism in the law.

One of her goals, she says, was to “resuscitate—not kill, not bury, but resuscitate—feminism and various feminisms in left thinking about power and sexuality.”

She writes: “Sex harassment, child sexual abuse, pornography, sexual violence, antiprostitution and anti-trafficking regimes, prosecutable marital rape, rape shield rules … have moved off the street and into the state.”

Halley faults feminists for putting on blinders to issues of sexuality and power involving others, such as gay men, transgender people and heterosexual men. As an example, she brings up the hard-fought enforcement of workplace norms against sexual harassment, including procedural rules that make it easier for plaintiffs to win and harder for defendants to defend. “These have been very good for women who are actually subject to sexual harassment,” she says. “But it has also been bad for gay men, because they are particularly subject to false accusations that they have come on to other men.”

Halley realizes that she treads in highly charged areas across a large legal domain touching upon intimate personal issues. While writing, she sometimes anticipated how her views might offend, but she was determined to advance her ideas despite the prickly reception she knew they might get in some quarters. “I’m trying to model how we can debate these matters without having a moralistic meltdown if somebody says something that isn’t politically correct,” she says. “Part of my argument is that we need better social and legal theory in order to be better leftists.”

Halley realizes that she treads in highly charged areas across a large legal domain touching upon intimate personal issues. While writing, she sometimes anticipated how her views might offend, but she was determined to advance her ideas despite the prickly reception she knew they might get in some quarters. “I’m trying to model how we can debate these matters without having a moralistic meltdown if somebody says something that isn’t politically correct,” she says. “Part of my argument is that we need better social and legal theory in order to be better leftists.”

Halley taught at Stanford Law School for 10 years before becoming a professor at HLS in 2000. Before attending Yale Law School, she was an English professor at Hamilton College. “Everything I do in legal studies is affected by my literary training,” she says, from her home in Dighton, Mass. “The humanities are a source of very crucial intuition about what we want to see. The humanities generate theory, and theory helps us to see the world differently.”

No one social theory, however, satisfies Halley. “You need to take a break from any social theory or you limit the way you see the world.” She also likes to take a break from many of the labels people put on one another. “Gay,” “straight,” even “woman”—“none of the labels works,” Halley says. “It is reductive to think of things as identities rather than performances.”

There are some labels Halley is comfortable applying to herself, however. “I’m a law professor,” she says. “I’m a teacher. I’m a really good cook. And I’m a leftist.”