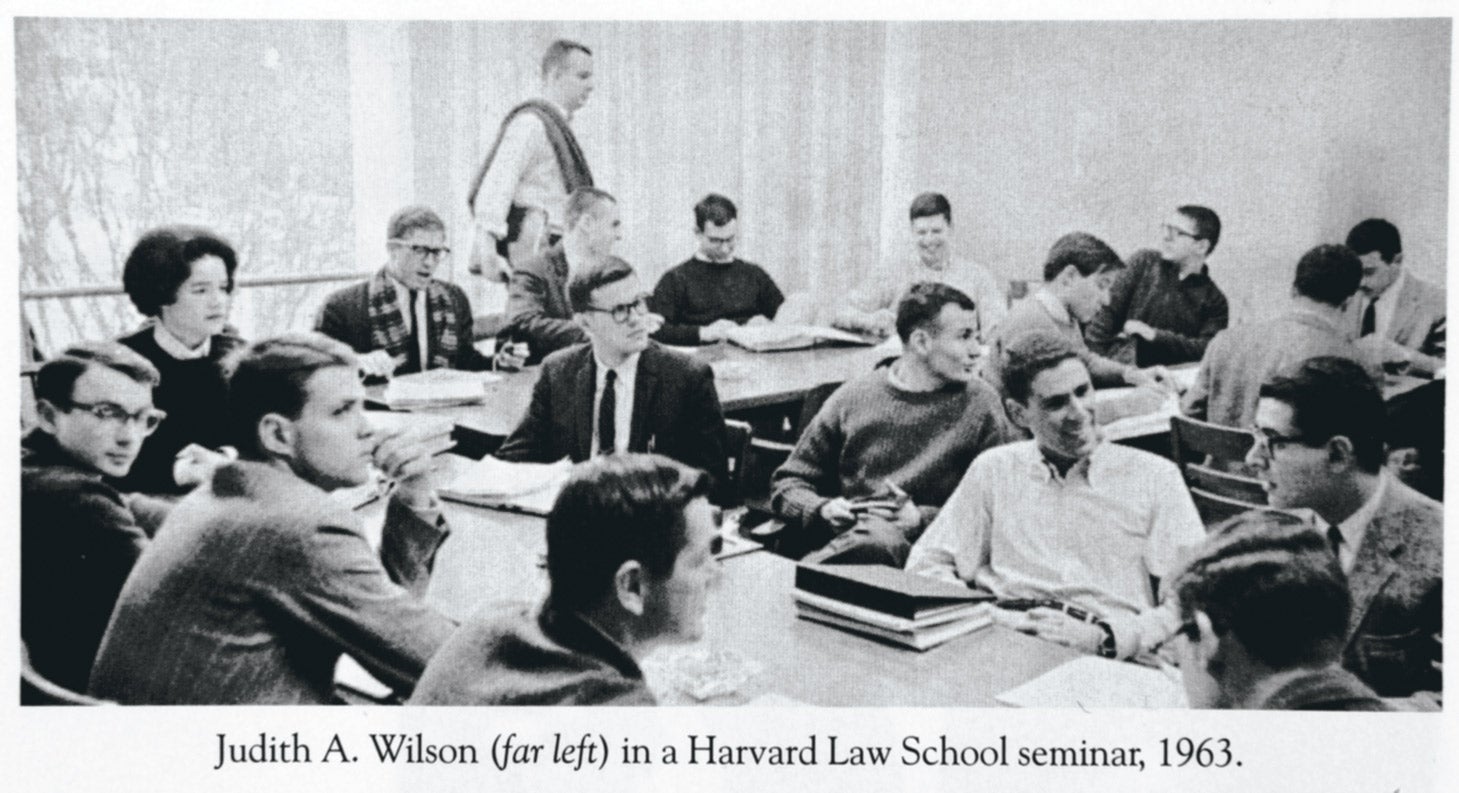

In recounting her years as a Harvard Law School student in the early ’60s, Judith Richards Hope could easily sound like she’s making up clichéd war stories about how hard it was for women in the male-dominated legal profession. After all, having to sprint across campus just to find one of the two women’s bathrooms does have a familiar “I walked 10 miles to school every day” quality to it.

But Hope and the 14 other women who graduated with 498 men in the HLS Class of ’64 did have to sprint across campus to the bathroom. They also had to endure the now infamous “Ladies’ Days,” special days one professor set aside for grilling the women students on cases involving underwear and the like. They had to deal with men who refused to sit next to “girls” in class and a dean who made each woman justify her presence at HLS.

“Today, such antics would probably be actionable,” says Hope of the challenges women faced daily at Harvard, one of the last law schools in the country to admit women. “We didn’t have enough outrage in those days. We just felt so privileged to be at Harvard Law School.”

In her new memoir, “Pinstripes & Pearls: The Women of the Harvard Law School Class of ’64 Who Forged an Old-Girl Network and Paved the Way for Future Generations” (Scribner, 2003), Hope reminds us that, whether these stories seem outrageous or just like ancient history to the law students who have followed, real women lived them.

A noted trial lawyer who served as an adviser to presidents Ford and Reagan, Hope is a founder of and partner at the Washington, D.C., office of Paul Hastings, and in 1989 became the first woman ever appointed to the Harvard Corporation. Though she and her contemporaries can now look back at the successful careers they’ve built, they faced real consequences for aspiring to have both a legal career and a family during the tumultuous ’60s, when the civil rights and women’s movements were still in their infancy.

“We were part of the first wave of women who would try to do it all, have it all, be it all,” Hope writes in her introduction. “It is probably a good thing that we didn’t fully understand what we were getting into.”

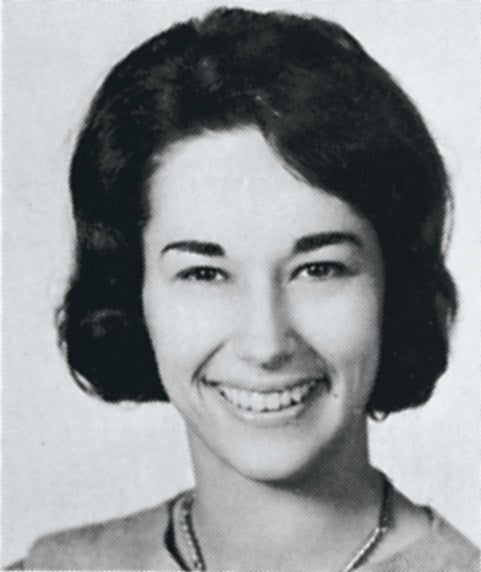

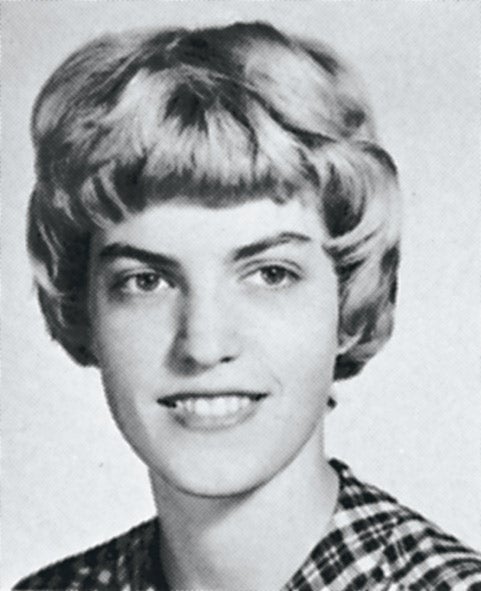

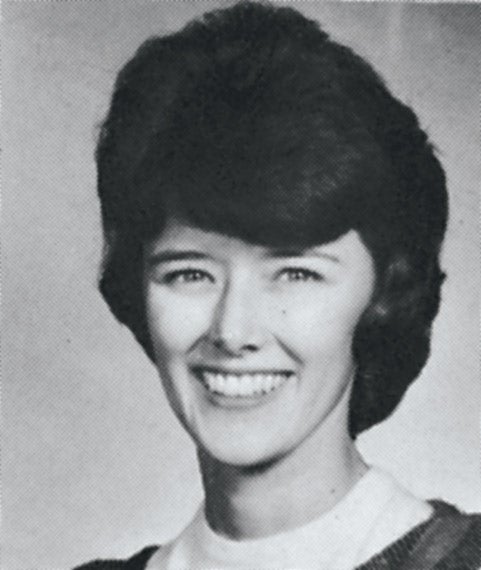

Part personal reflection, part social history lesson, Hope’s book captures both the high notes and the very low points in the illustrious careers of her women classmates–who include former Congresswoman Patricia Schroeder, U.S. Court of Appeals Judge Judith Rogers and Environmental Protection Agency attorney Alice Pasachoff Wegman. Former U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno graduated a year before, while Elizabeth Dole–now a U.S. senator from North Carolina–graduated a year after.

For all their achievements, they faced nearly as many barriers to their success.

“We got what we were hoping and aiming for in the opportunity to go to Harvard,” Wegman says, “so the extent of the discrimination came as somewhat of a surprise.”

Always a distinctive minority in law school, law firms and courtrooms, the women learned early to stick together.

“There’s something about being totally surrounded that causes you to bond,” Schroeder recalls. “It was more like a foxhole mentality than your normal educational experience.”

They became allies in a place that was legendary for its cutthroat competitiveness, even preparing each other for potentially embarrassing Ladies’ Day inquisitions and for the dean’s grilling over dinner.

When Dean Erwin Griswold asked each woman, “Why are you at Harvard Law School, taking the place of a man?” Schroeder was infuriated, and still is to this day. “I was sitting there thinking, ‘What am I going to say that’s profound?’” she recalls. But before she had the chance, her classmate Ann Cronkhite Goldblatt—now a bioethicist at the University of Chicago—said that she’d come to Harvard because Yale turned her down.

“It broke all the tension,” says Schroeder, “but I thought, ‘Why in the world are we playing this game?’ It was astounding to me.”

Schroeder says she was not intimidated by the dean’s dinner party and always felt she’d had a right to be at Harvard. “I didn’t let it get to me. I did what I had to do and got out of there. It was never a warm and fuzzy place—you couldn’t even find a bathroom—so why would you hang around?”

Published in January, “Pinstripes & Pearls” went into its second printing only six weeks later. Not bad, considering Hope nearly gave up on it after her daughter, Miranda, gave her first draft a scathing review.

“She trashed it,” Hope said during a visit to HLS in February to promote the book. While Hope had been focused on how much she and her classmates had overcome—the gender discrimination in school, at law firms and in courtrooms—she’d overlooked the impact that such obstacles had had on their lives. Miranda, she said, remembered the countless nights that Hope had come home exhausted or angry at being passed over for a job. “You haven’t told the whole story,” she said to her mother.

Hope was devastated at first and put the book aside for nearly two years. But after hundreds of hours of interviews with classmates, Hope found the whole story. Along with their many triumphs, the women interviewed candidly share some of their darkest moments in “trying to do it all”: the career setbacks they suffered in order to raise their children, the stress of juggling high-powered, high-profile jobs and the myriad details of home and family, and even—in one case—the brief contemplation of suicide.

On a recent book tour, Hope learned that the book has had resonance with a younger generation of women professionals and women law students: “I have been told again and again that our histories are giving them new perspectives, helping them make it through their own challenging lives, and giving them optimism about their efforts to juggle the requirements of a demanding profession and the very real needs of their families.”

That, she says, is the goal of the book. Now that nearly 50 percent of HLS students are women, younger alumnae may believe that the barriers to opportunities for women are gone forever. But Hope says some difficulties are here to stay.

“It’s the same struggle: Women have a limited time in which they can have children, and that’s not true for men,” she says. “Women also have a limited time in which they can build a career. The tough thing is, it’s the same time. While some women can now work from home and raise a family, many women still can’t work from home—doctors, engineers, lawyers. You can’t do it, so you’re constantly in this tug-of-war between your desire to have a fulfilling and productive career and your desire to raise wonderful children. Most of the women in my class did both. I felt we had a story to tell that would be of help and maybe an inspiration to young women today.

“I don’t really know whether young women today don’t know or have forgotten, but I think its standard operating procedure to believe that things have basically always been relatively open. But it wasn’t always this way. It’s important to remember because you have to be vigilant.”

For many of the women, the lifelong friendships—the “Old-Girl Network”—that formed amid the pressure of law school have sustained them to this day: “For us, it meant everything,” Hope says. “Is it still as powerful? Yes. Do younger women understand the vital need to help each other? I don’t think so. Men have strong networks, and they really help each other. When women do that, it really makes a difference, and they should. There is the old saying, ‘If you don’t hang together, you’ll hang separately.’ There is really strength in numbers.”

The Women Graduates of the Class of ’64: Where They Are Today