During World War I, about 400,000 “enemy aliens” were imprisoned by all sides in camps on nearly every continent. During that time, Germany’s only exclusively civilian prison camp, Ruhleben Gefangenenlager, became a model of civil functionality.

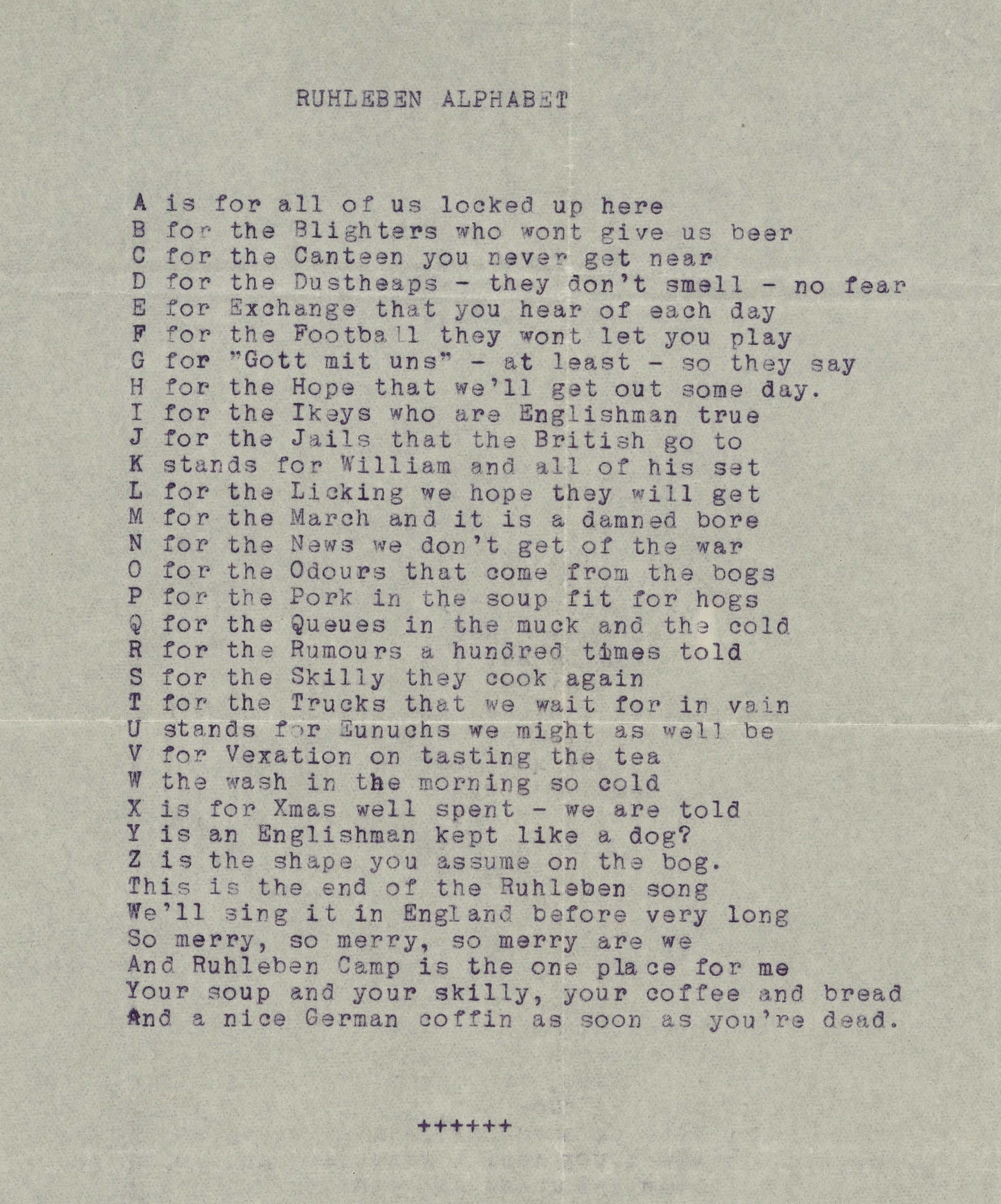

Ruhleben—“quiet life,” in German—refers today to both the now-vanished site on the outskirts of Berlin and a pair of archives at Harvard Law School Library Historical & Special Collections. The Maurice L. Ettinghausen and John C. Masterman collections include photos, posters, publications, drawings, ticket stubs and more: ephemera that shed light on civilian internment from 1914 to 1918.

“It’s one of the most heavily used [HLS] collections,” said Curator of Digital Collections Margaret Peachy of the Ruhleben materials. They are especially popular with genealogists, historians, and sociologists, and with students of what makes society civil. Beginning in 2008, the two archives were digitized, making more than 11,000 images more accessible.

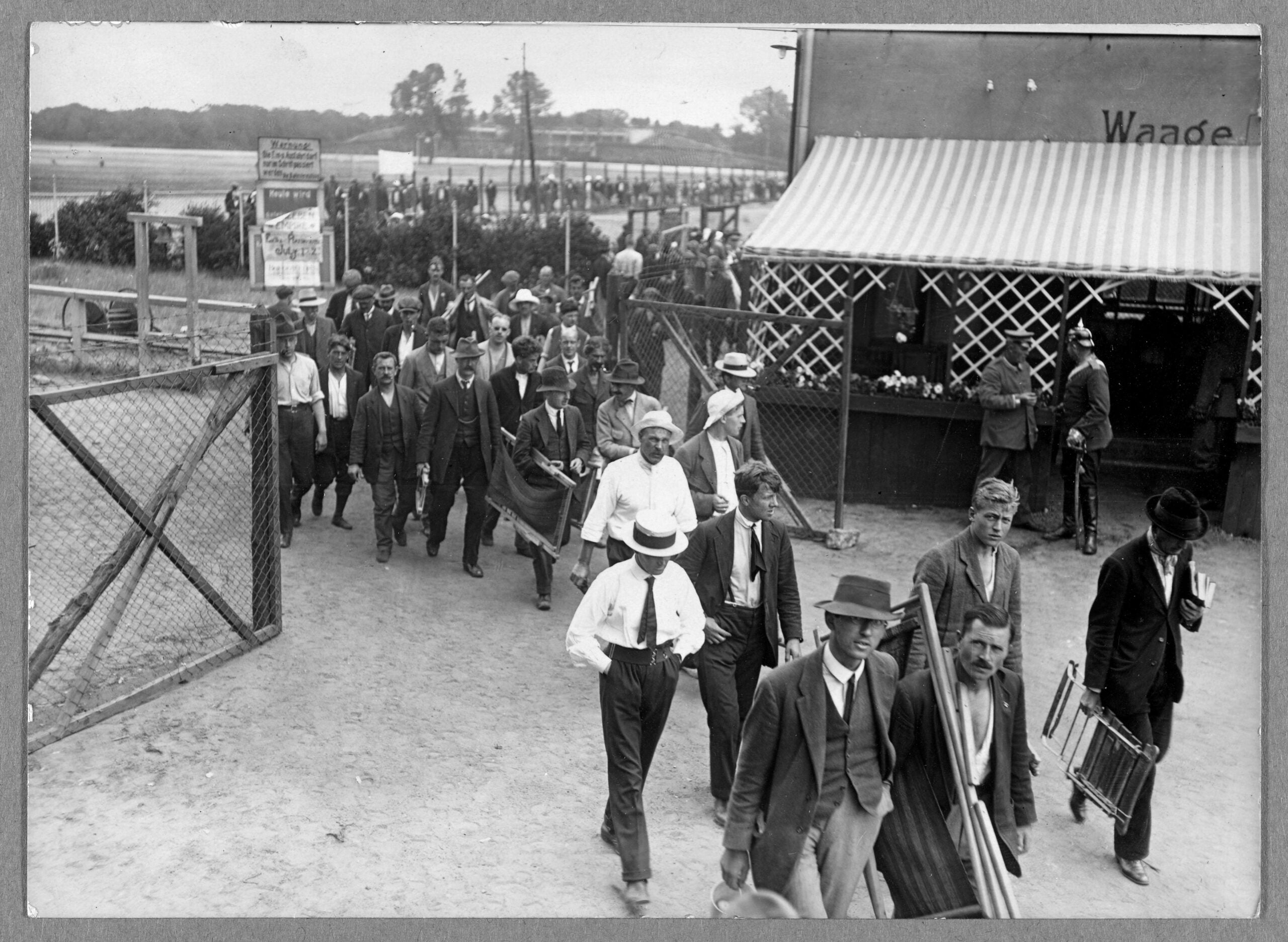

Ruhleben is a unique lens for viewing the fate of civilian prisoners. Following a declaration of war on Aug. 4, 1914, negotiations between Germany and Great Britain regarding an all-for-all trade of civilians quickly failed. On Nov. 6, about 4,000 British men aged 17 to 55—tourists, businessmen, expatriates and merchant seamen—were arrested and sent to Ruhleben. (Women, children and the elderly were exempt.) By February 1915, all other male Commonwealth civilians in Germany were detained, and Ruhleben’s wartime population peaked at 4,273.

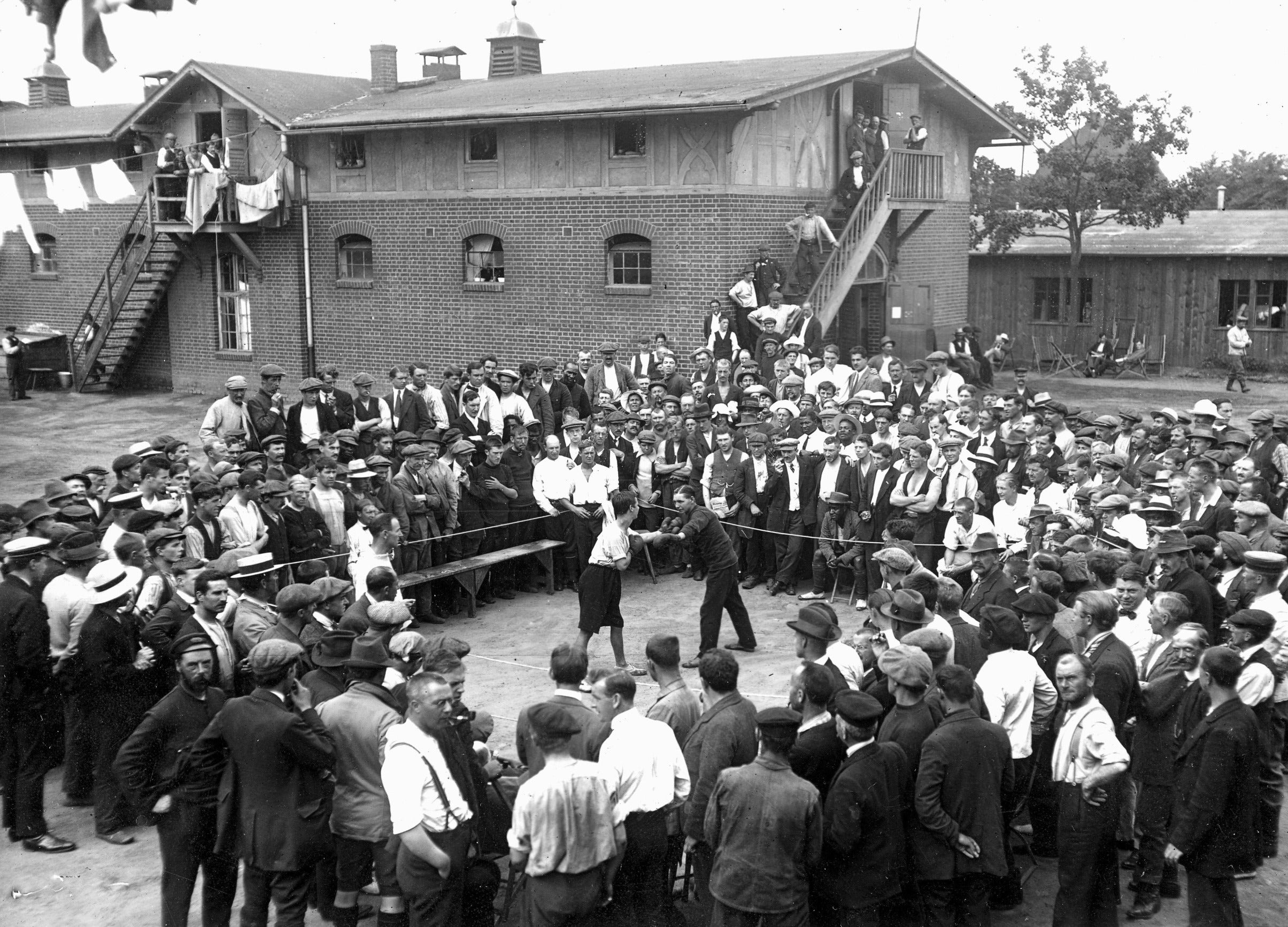

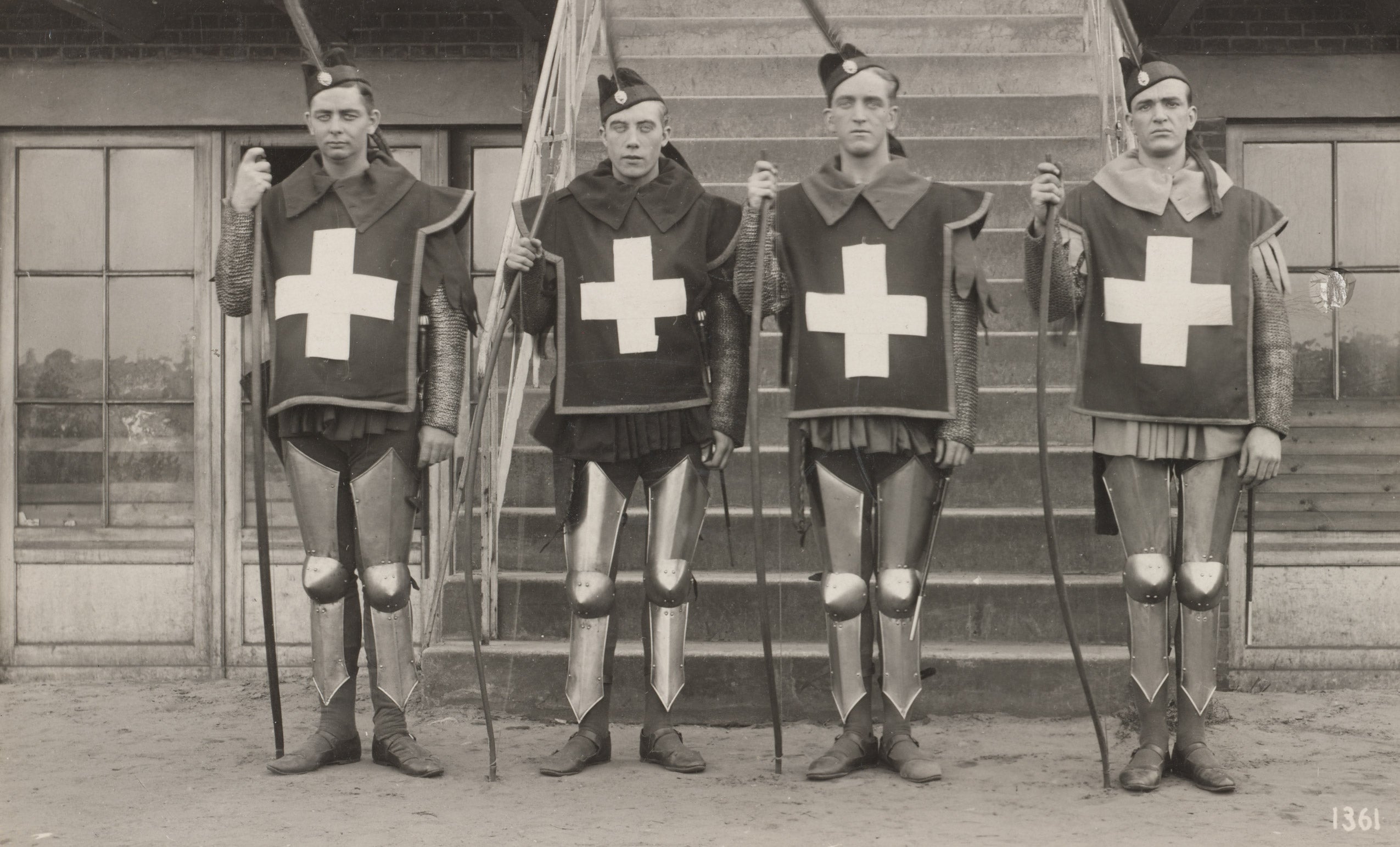

The first inmates were assigned freezing stalls in the former horseracing track, with no power or ventilation. But by 1915, inmates had gotten German authorities to let them take over the administration of the camp. In many ways, Ruhleben became a miniature Britain, with its own economy, a home-rule administration, elections, a clinic, a police force and sports teams. There were food and nursery gardens, theaters, and schools. (“There is so much studying,” wrote an Anglican bishop who visited in 1916, “that I call it the University of Ruhleben.”)

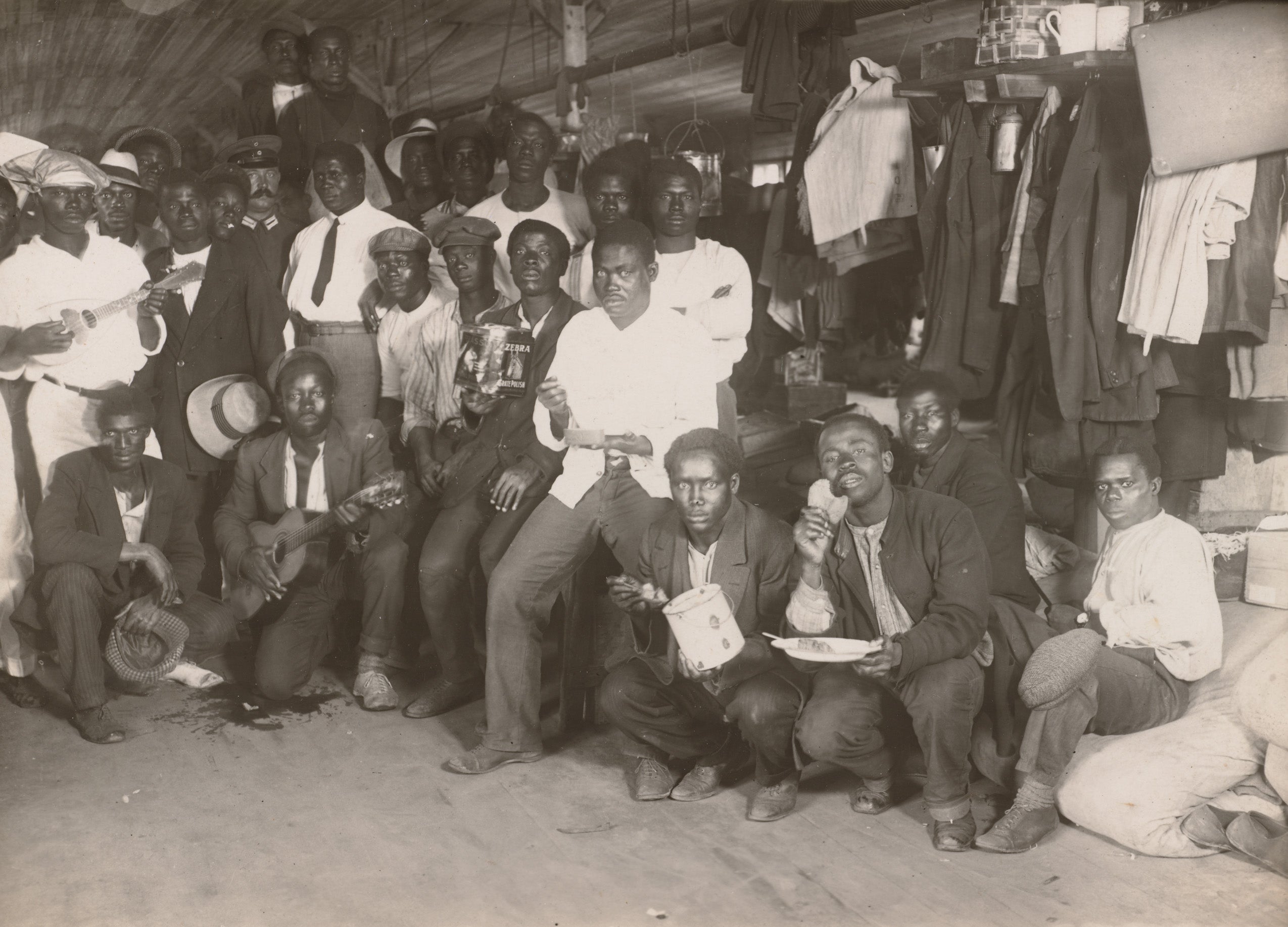

In this miniature Britain, however, English class distinctions still held sway. So did social prejudices. For a while, the camp’s 70 Jews were segregated in run-down Barrack 6; 100 black inmates, sailors from the West Indies and British West Africa, lived in Barrack 12—banned from all social activities except sports.

Ruhleben was no utopia, but fewer than 60 inmates died between 1914 and 1918, most from natural causes. Meanwhile, the war killed 16 million and wounded 20 million. In wartime military prisons, at least 750,000 died.

Since being digitized, the collections have only grown in popularity. With the centennial of World War I, history buffs are among those who add traffic to the site. So do those who research camps for war-displaced civilians—model or otherwise. “Unfortunately,” said Peachy, “that history is repeating itself.”