“Cooperation: A Political, Economic, and Social Theory,” by Bernard E. Harcourt ’89 (Columbia University Press)

In a world beset by serious crises such as climate change and threats to democracy, progress is hampered by conflict and polarization, according to Bernard Harcourt. Often one side preaches rugged individualism while the other preaches government intervention, with neither achieving the large-scale collective action to prevail. The author, a professor of law at Columbia University, charts a different course based on what he calls “coöperism,” in which “the well-being of everyone in society and the welfare of the environment are placed ahead of the profits of the few. He chronicles examples of cooperative efforts in business and daily living, such as credit unions, nonprofits, and mutual aid, and advocates for a cooperative democracy that draws on longstanding, successful practices, in which people work together to benefit all participants.

“Data and Democracy at Work: Advanced Information Technologies, Labor Law, and the New Working Class,” by Brishen Rogers ’06 (MIT Press)

In today’s labor politics, writes Brishen Rogers, “knowledge and control are centralized, surveillance is constant, and line-level workers have little autonomy and no voice on the job.” The professor at Georgetown University Law Center argues that workers’ power began to decrease in the 1970s, spurred by changes in laws that “treat the enterprise more like the employer’s sovereign property” along with technologies that monitor workers’ actions, including efforts to unionize. In addition, he writes, many major companies purchase labor without hiring workers as employees, thus avoiding legal responsibilities. Rogers advocates for reforms such as guaranteeing the rights of workers to participate in workplace governance through collective representation and banning forms of workplace surveillance.

“I Am Debra Lee: A Memoir,” by Debra Lee ’80 (Legacy Lit)

Once called too nice, Debra Lee shares her story of finding her voice and confidence to ascend to and succeed in the position of CEO of Black Entertainment Television. Raised in the segregated South, she recalls her student days at Brown University and Harvard Law, her decision to leave a large law firm for a general counsel position at BET, and her encounters with luminaries such as Aretha Franklin and Oprah Winfrey. She is frank about myriad challenges she faced in her 32 years at BET (the last 13 as CEO), including raising a young family while handling an overwhelming workload and managing a team of men. At the same time, she celebrates the opportunities she’s had to help showcase the power and beauty of Black culture that she cherishes.

“In a Bad State: Responding to State and Local Budget Crises,” by David Schleicher ’04 (Oxford)

A professor at Yale Law School and expert in local government law, David Schleicher offers guidance for federal officials on how to respond when a state or city faces fiscal crisis. He examines historical cases, from Alexander Hamilton’s plan for the federal government to assume state debts after the Revolutionary War through the federal government’s response to local and state fiscal distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. The U.S. government may provide money to indebted states or cities, encourage them to pay their debts, or allow them to default on their debts — all options that may lead to bad outcomes, Schleicher writes. He proposes steps that federal officials can take to facilitate fiscal stability in local jurisdictions and help the country be better able to deal with inevitable economic shocks.

“A Minor Revolution: How Prioritizing Kids Benefits Us All,” by Adam Benforado ’05 (Crown)

At the turn of the 20th century, reformers sought to improve the plight of children living in extreme poverty, who were relegated to working long hours in dangerous conditions. Despite much social progress since then, children still suffer due to a society that fails to focus on their welfare, argues Adam Benforado, a professor of law at Drexel University. Backed by research on children’s development and cognitive capacity, he proposes a list of core rights to which children should be entitled. He also calls for policies such as paid family leave and investment in early education, housing, and health care. We are now giving children a worse life than our parents gave us, he writes, and prioritizing children is the best way to address society’s major challenges.

“Roe: The History of a National Obsession,” by Mary Ziegler ’07 (Yale University Press)

Mary Ziegler, a professor at the University of California, Davis, School of Law, argues that Roe v. Wade has attracted more public scrutiny than perhaps any other Supreme Court case “because it has been used to express nuanced, complicated ideas about abortion that the Supreme Court supposedly put out of reach in 1973.” She shows how supporters and opponents of Roe have bolstered their cause by offering different perspectives on what the concept of “choice” means for women. Ziegler, who completed the book last year before the Court’s ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, wrote that even if Roe were reversed, it would “remain a rallying cry for those with different views about everything from race to religion.”

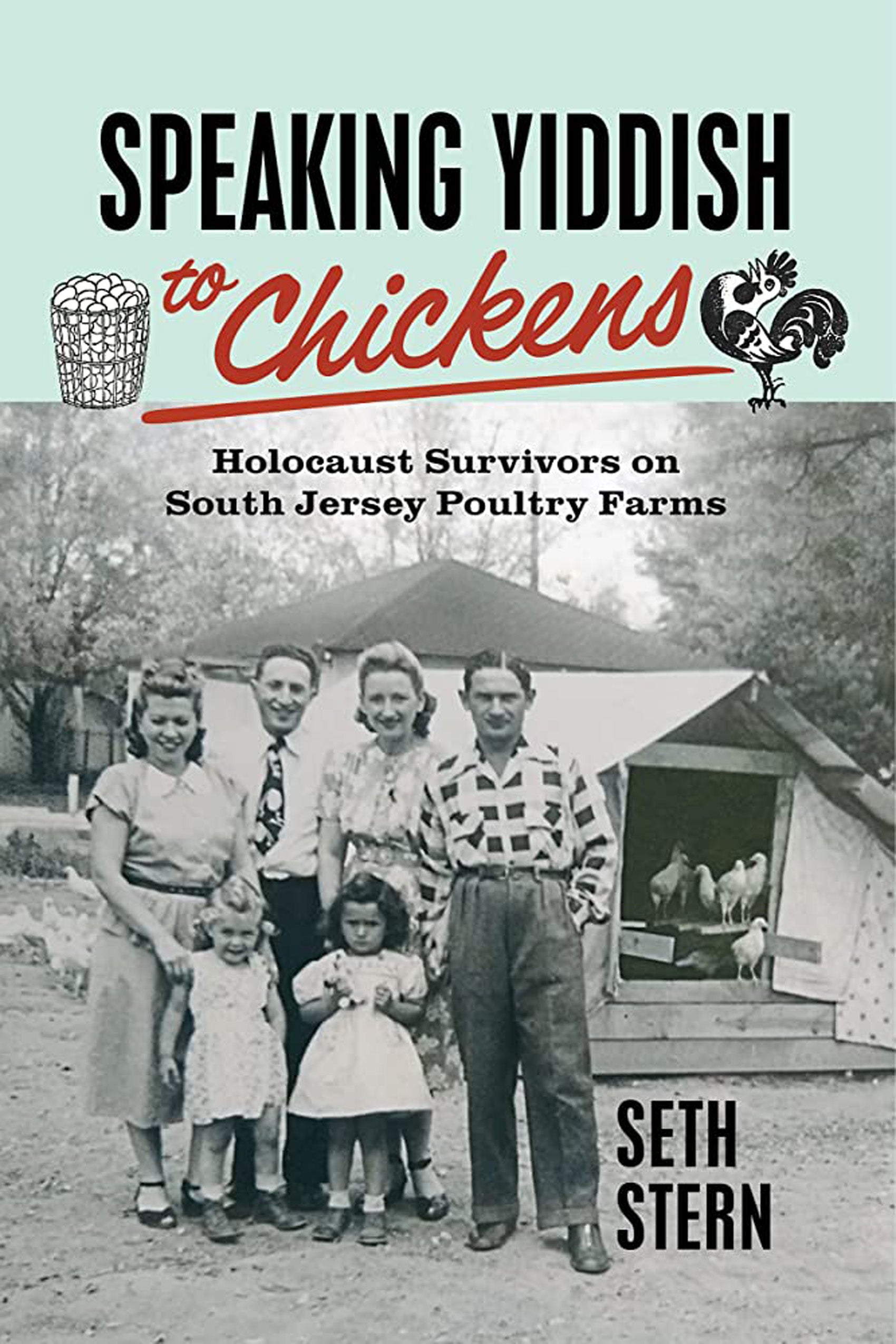

“Speaking Yiddish to Chickens: Holocaust Survivors on South Jersey Poultry Farms,” by Seth Stern ’01 (Rutgers University Press)

When he was home studying for his law school exams, Seth Stern had lunch daily with his grandmother, and conversations that inspired his book on the experiences of his family members and other Jewish immigrants who ushered in a largely forgotten era of Jewish poultry farming in south New Jersey. He traces their passage from Europe after World War II, the reception they received in their new homeland, and their efforts to build community. Known as “Grine,” a play on the Yiddish word for greenhorn, the farmers proved to be the final wave of American Jewish agricultural workers. Though the poultry business became unsustainable, Stern’s grandmother told him before she died at age 96 that she had no regrets about settling in rural New Jersey, and that they lived a good life.

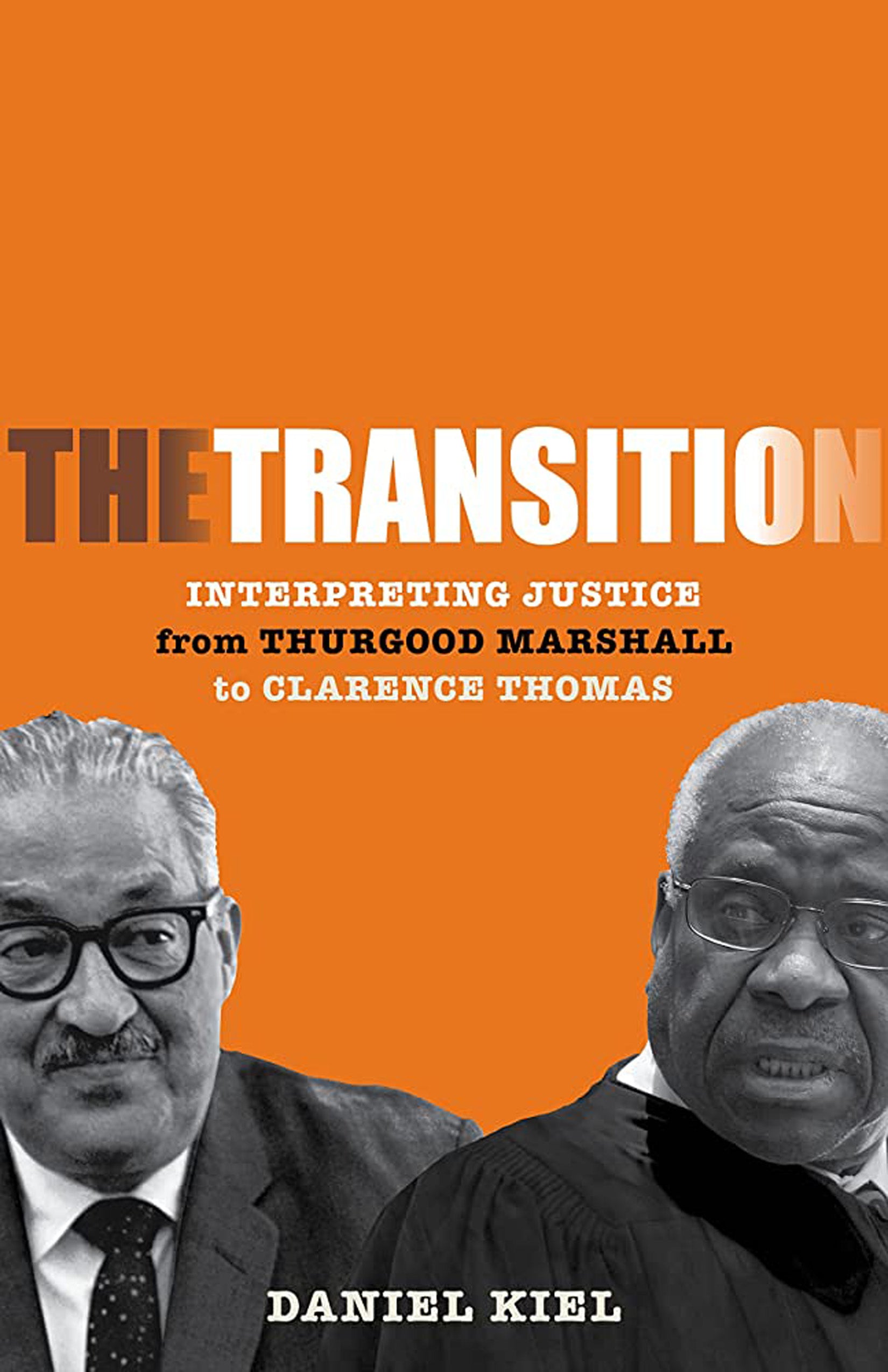

“The Transition: Interpreting Justice from Thurgood Marshall to Clarence Thomas,” by Daniel Kiel ’04 (Stanford University Press)

Clarence Thomas succeeded Thurgood Marshall on the Supreme Court. Their contrasting judicial philosophies give insight into the relationship between citizens and their government and the social, legal, and political debates that have defined the past century, writes Daniel Kiel, professor of law at the University of Memphis. The author examines how the justices’ upbringings shaped their views on race and their approaches to cases on the Court — particularly those involving education, an important factor in their lives — as well as the constitutional issues they encountered. Kiel surmises that the harm they both suffered as students led them to contradictory perspectives on achieving progress in the nation, including how to uplift Black citizens.

“Unwired: Gaining Control over Addictive Technologies,” by Gaia Bernstein LL.M. ’00 (Cambridge University Press)

Government intervention helped drastically reduce tobacco use. Gaia Bernstein argues that it should do the same for another addictive activity: technology use. A professor at Seton Hall University School of Law, she explores how tech companies manipulate people to use their products, and she also looks at the deleterious effects of screen time, especially on children. Potential remedies include regulations against addictive design and deceptive practices as well as laws that would raise awareness of the risk of overuse through labeling and advertising. We do not have to go back to a world of no online connection, she writes, but “[g]oing forward means finding a better balance between our technologies and ourselves.”

“Who Speaks for You?: The Inside Story of the Prosecutor Who Took Down Baltimore’s Most Crooked Cops,” by Leo Wise ’03 (Johns Hopkins University Press)

Leo Wise tells the story of the investigation and prosecution of the Baltimore Police Department’s Gun Trace Task Force. The book is based on his experience as the lead federal prosecutor of the police officers who robbed local residents. The victims charged that the police “acted like an occupying army” in overwhelmingly Black East and West Baltimore. All members of the task force were arrested on federal racketeering charges and two went to trial, which Wise also covers in the book. Both officers were found guilty, with the verdict read by the foreperson, the only Black male on the jury, speaking for the victims.