“Outside of this context of shared assumptions, e-mail functions like bad poetry where any meaning can be put into the e-mail depending on what you’re trying to see. And that makes it a very dangerous type of document outside of context that people can control.”

-Professor Lawrence Lessig, during March 11 interview about e-mail as legal evidence in court on “Morning Edition,” National Public Radio.

“The construction of a state that prohibits discrimination and protects the rights of minorities is now a central aspiration of civilization in this century. The entire human rights corpus is premised on these preeminent norms. Living with difference and ‘otherness’ within the borders of a state is required — and assumed to be essential for human development. The very legitimacy of a state partially depends on its relationships with different communities. But as the examination of the former Yugoslavia clearly demonstrates, living with difference is much more difficult than international society is willing to acknowledge.”

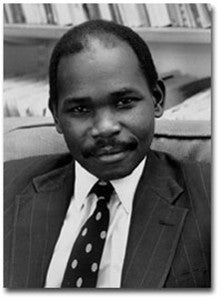

-Makau Mutua LL.M. ’85 S.J.D. ’87, visiting HLS professor, from his April 21 op-ed in the Boston Globe.

“A Web page simulating, or even glorifying, violence and hatred is not outside the First Amendment’s protection any more than are disgusting board games, magazines, or political tracts. The same First Amendment that safeguards the right of Nazis to march through Skokie protects the right of an adult to put virtual machine guns aimed at lifelike human targets on his or her computer screen.

“At the same time, Internet speech doesn’t have more constitutional protection than speech disseminated in a more old-fashioned and limited manner. In particular, direct threats or other messages that by their very utterance cause harm receive no more protection on the Internet than anyplace else. Releasing a computer virus through e-mail deserves no greater immunity than crying ‘Fire’ in a crowded theater.”

–Professor Laurence Tribe ’66, from his April 28 op-ed in the New York Times, occasioned by national debate about the possible role in the Littleton, Colorado, school massacre of hate speech and violent computer game playing over the Internet.

“I have a question about whether we should be inducing women to sell their eggs and to sell parenting rights.”

-Professor Elizabeth Bartholet ’65 —who has called for a halt to egg donations and other uses of reproductive technology until a national commission is formed to set rules—in U.S. News & World Report, April 12.

“Much of medieval canon law has passed over—often unnoticed—into the laws of the state. And many of the legal reforms the medieval papacy promoted [such as rational trial procedures, legal protection of the poor] command respect even seven and eight centuries later.”

-Harold Berman, professor emeritus, quoted in “2000 Years of Jesus,”Newsweek, March 29, about the influence of Christian ideas on the modern world.

“Sacco and Vanzetti [the famous case] plays a role in the psyche of some Massachusetts people. Indeed, I think it probably explains why the message of the Vatican has taken hold, I think, more strongly among Irish Catholics and Italian Catholics in Massachusetts than elsewhere. I think people with immigrant backgrounds have been told terrible stories of discriminatory application of the death penalty against immigrants.”

-Professor Alan Dershowitz, during March 23 report on Massachusetts’ death penalty debate, “All Things Considered,” National Public Radio. Massachusetts is one of only 12 states that do not have the death penalty. Sacco and Vanzetti were executed in 1919, with many believing the anarchists were convicted due to prejudice against immigrants.

“The inherent faults in the Independent Counsel Act cannot be fixed merely by tinkering with the law’s details. But it would be a mistake for Congress simply to let the act expire without replacing it with a different system. Doing so would mean that the next time serious charges of criminal misconduct are raised against a President or other top officials, much of the public will be left with suspicions that any investigation might be influenced by politics or personal interest. . . .

“[A way to] quiet such fears while also avoiding the institutional flaws [of the current system] is to assign the investigation and prosecution of criminal charges against high officials to a pre-existent, permanent unit of government, and then to couple the assignment with strong safeguards against outside influence. The most suitable unit is the Justice Department’s criminal division, which is headed by an Assistant Attorney General. In fact, such a system was in place from 1979 to 1981, after Watergate and before the Independent Counsel Act took full effect.”

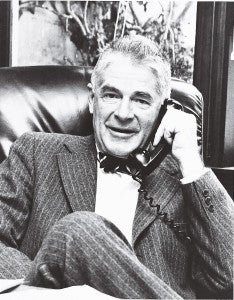

–Archibald Cox ’37, professor emeritus, and Professor Philip Heymann ’60, from their March 10 op-ed in the New York Times.