Former solicitor general puts Alito memos in context

Judge Samuel A. Alito Jr.’s opponents have seized upon two memorandums he wrote when he was a junior lawyer in the office of the solicitor general….

“Determined to fit the man to the Scalito caricature with which they hope to defeat his nomination to the Supreme Court, Judge Alito’s detractors ignore the context and the content of both documents….

“What is remarkable … is that Judge Alito recommended against taking the position that more senior, politically appointed officials were urging the solicitor general to take before the court. In the abortion case, not only the head of the civil division but also other high-ranking officials were urging that I, as the solicitor general at the time, ask the court to overturn Roe v. Wade. The bottom line of Judge Alito’s memo was that I should not do that.

“Judge Alito did note that the lower courts’ decisions in Thornburgh were highly irregular on technical, procedural grounds (a position with which Justice Sandra Day O’Connor agreed, in her dissent when Thornburgh reached the Supreme Court), and that Roe might well be modified–as it has been–in less radical ways over the years….

“I did not follow Judge Alito’s advice and instead asked that Roe be reconsidered and overturned because I thought the administration had the right to have its position put before the Supreme Court in a forthright but professionally correct way. Judge Alito in his memo correctly predicted that the court would react with hostility to the administration’s argument.”

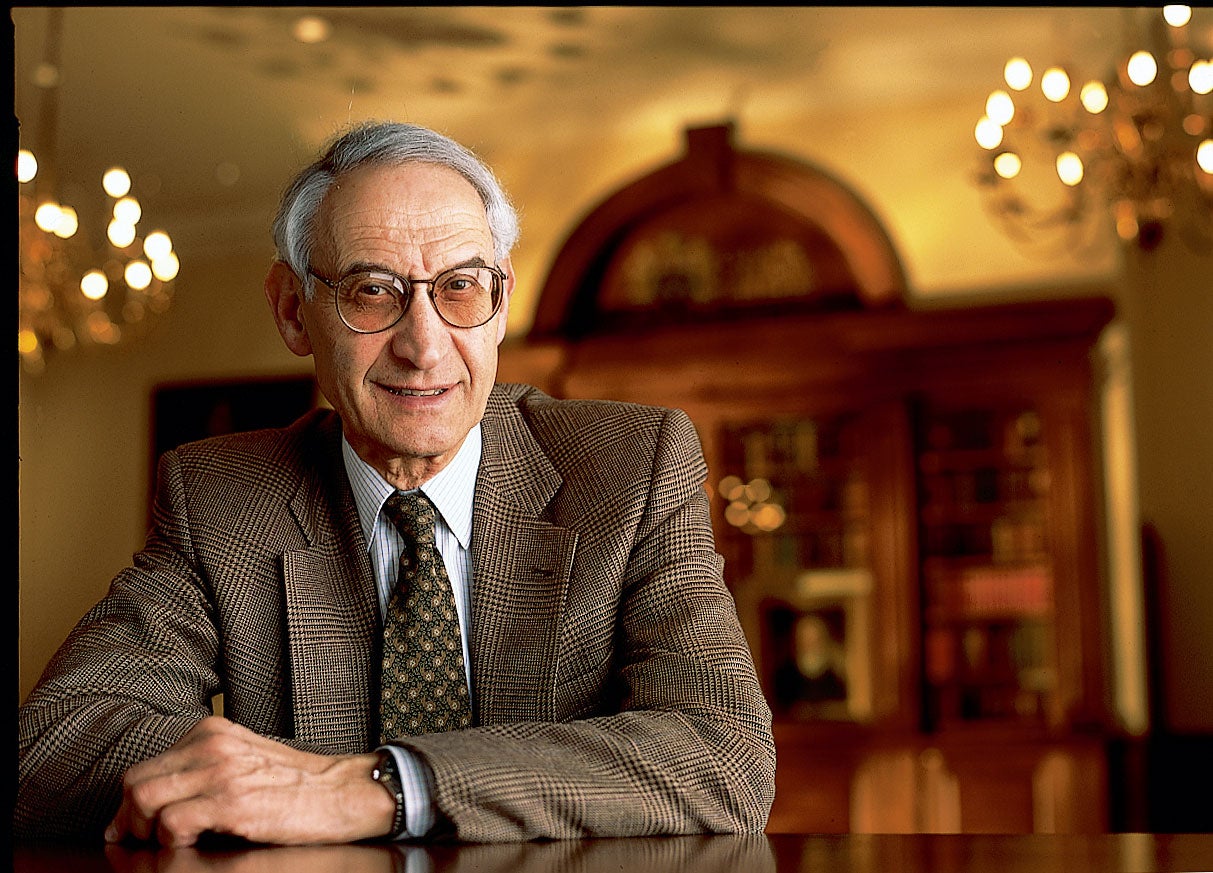

Professor Charles Fried, The New York Times, Jan. 3, 2006.

Balancing act

Some democratic members of the Senate Judiciary Committee have argued that Judge Samuel A. Alito’s nomination to succeed Justice Sandra Day O’Connor merits more thorough scrutiny, if not outright rejection, because it would disturb the ‘balance of the court.’…”

“As a matter of principle, to suggest that presidents should select nominees who will leave the court’s ideological composition intact implies that the court’s jurisprudence is always precisely where it should be–that nothing can ever be gained from a change in the perspective, experience or philosophy of any justice. Even more troubling still, the baseline for assessing ‘balance’ at any given moment is almost entirely arbitrary. If today’s balance differs from that of an earlier court, presumably past presidents and Senates already violated the balance principle when they selected and confirmed the members of the court that we now seek to preserve.”

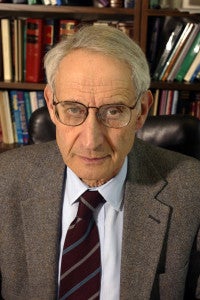

Professor John Manning ’85, The New York Times, Nov. 10, 2005.

Conservative hypocrisy

[C]onservatives are more or less devoted to a legal system and a policymaking approach that assume situational influence is, in the vast majority of circumstances, trivial and irrelevant. Get the government out of our lives so that we can be ‘free to choose,’ the argument goes. Unchain markets so that people can pursue their own ends as they see fit….

“But … the right does sometimes underscore the importance of situation. According to the conservative narrative, the situational force that is most harmful and significant is that of the ‘intellectual class’ and the institutions where its ideas are developed, employed and advanced….

“Hence, the same individuals who are eager to point out how Supreme Court justices are vulnerable to situational manipulation–who suggest that our country is being destroyed because of the powerful influence of liberal elites over our culture and, in turn, our culture over us–are otherwise adamant in denying the role of situation in the lives of consumers, workers, voters, parents, criminals and any justices who happen to be strict constructionists.”

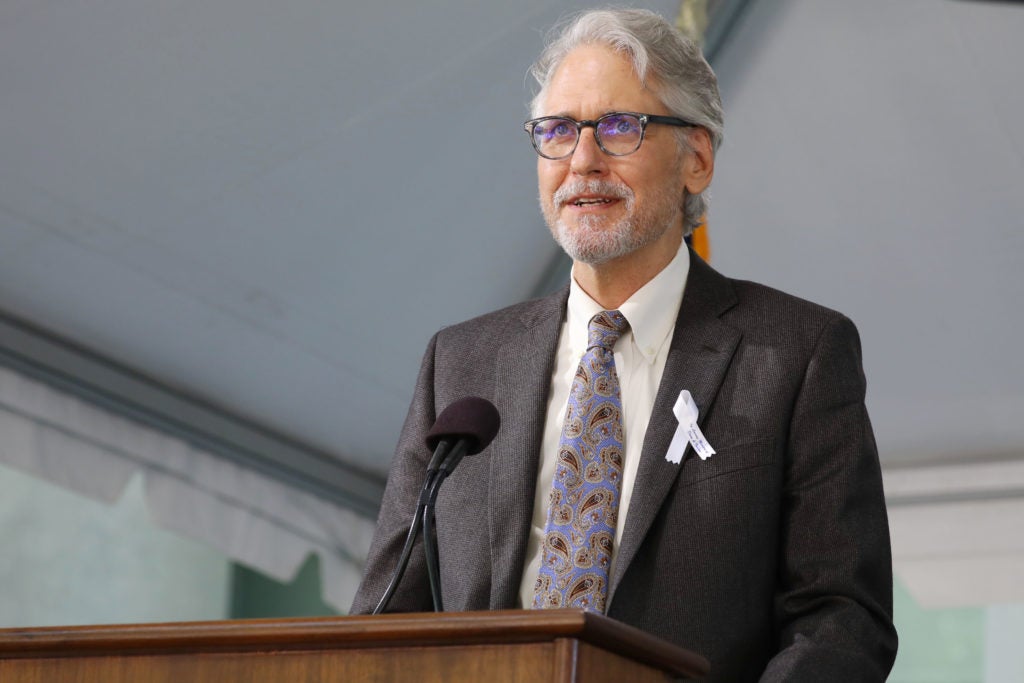

Professor Jon Hanson and Adam Benforado ’05, The Baltimore Sun, Dec. 12, 2005.

What’s wrong with the Court citing foreign law?

The problem is not reference to foreign law: It is how foreign law is used by judges who usurp powers reserved under the Constitution to the people and their elected representatives….

“Take Lawrence v. Texas, the decision striking down criminal penalties for homosexual sodomy, where Justice Kennedy, joined by Justice Breyer, wrote, ‘The right petitioners seek … has been accepted as an integral part of human freedom in many other countries. There has been no showing that in this country the governmental interest in circumscribing personal choice is somehow more legitimate or urgent.’ The remarkable implication is that it is up to our legislatures to justify a different view of human rights from that accepted elsewhere. This gives short shrift to the fundamental right of Americans to have a say in setting the conditions under which they live–the right that is at the very heart of our unique democratic experiment. Contrast the responsible use made of foreign law by Chief Justice William Rehnquist in Washington v. Glucksberg, to support Washington state’s legislative prohibition of assisted suicide in an opinion noting that in ‘almost every state–indeed, in almost every western democracy–it is a crime to assist a suicide.’

“The importance of the distinction between these two modes of use cannot be exaggerated. It is not only a question of respecting the separation of powers. Those who believe the Washington legislature got it wrong can work to change the law through the ordinary democratic processes of persuasion and voting. But in the U.S., unlike in countries whose constitutions are easier to amend, the court’s constitutional mistakes are exceedingly hard to correct. The unhealthy ripple effects of judicial adventurism are many: Legislatures are encouraged to punt controversial issues into the courts; political energy, lacking more constructive outlets, flows into litigation and the judicial selection process.”

Professor Mary Ann Glendon, The Wall Street Journal, Sept. 16, 2005.