As admirers across the United States and around the globe mourn the passing of former President Jimmy Carter on Dec. 29, 2024 at the age of 100, three current and former Harvard Law professors share their memories of working with him and reflect on his life and legacy.

Retired U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer ’64, now the Byrne Professor of Administrative Law and Process, worked with the Carter administration as an aide to Senator Ted Kennedy before the late president appointed him to serve on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. William Alford ’77, the Jerome A. and Joan L. Cohen Professor of Law, recalls briefing President Carter about the People’s Republic of China, and recounts how Carter helped free a fellow scholar from imprisonment in Sudan. And in an op-ed published in The New York Times, USAID Administrator Samantha Power ’99 argued that while much attention is paid to his post-presidential work, “Jimmy Carter’s elevation of human rights in U.S. foreign policy offers many urgent lessons for today.”

Read their reflections below.

Former President Jimmy Carter was extraordinary.

In 1984, desperate to help secure the release of the noted Sudanese scholar Abdullahi An-Na’im from imprisonment for his political and religious views, and possible execution, I reached out to President Carter (for whom I had earlier done briefings on China). Invited to meet in Plains, I don’t think I have ever been more anxious, as I thought the fate of my classmate and dear friend Abdu turned on that meeting, earlier efforts (e.g., an Amnesty International campaign) had not yet been successful. But before I was halfway through my presentation, President Carter said he had heard enough, especially in light of the memo I had sent ahead (which he knew in detail). He pulled out pen and paper to write a personal letter to then President Gaafar Nimeiry saying that he understood some underling had mistakenly imprisoned Professor An-Na’im and that he was sure President Nimeiry would want to remedy this mistake (and, by the way, also come meet the Carters once again). President Carter then via an aide sent the letter off to the Sudanese Embassy. Not too long after, Professor An-Na’im was released from prison and on his way to UCLA (where I then taught). While other factors (on-going campaigns, political changes in Sudan, etc.) may also have played a role, I am in awe of President Carter’s generosity, the instant eloquence of his letter, and, of course, its result.

In a fitting irony, after being a fellow in the Human Rights Program at Harvard Law School in 1991 and later executive director of Human Rights Watch/Africa, Abdullahi An-Na’im in 1995 joined the faculty of the Emory University School of Law, where he was the Charles Howard Candler Professor (now emeritus) and, fittingly, a source of wisdom for the Carter Center.

My other interactions with President Carter were certainly less consequential but also evidenced how remarkable he was. I had the privilege of briefing him and Mrs. Carter prior to their first trip to the People’s Republic of China in 1981 (he had been to China during its civil war in 1949 while he was in the Navy, but he was unable to go while president even though he had normalized relations) and of giving a talk at the Carter Center before his final trip to China. What stands out, even after more than 40 years, is his blend of incisiveness, humility, and graciousness. Even as he was grilling me, I was struck, sitting his living room, by how most of the artwork and photographs were about or by family, rather than his career. And I was flattered when, after our session, he invited me into his woodworking shop and took the time to explain the qualities of different kinds of wood from maple to pine (something new to this city boy).

He was an extraordinary person and I feel so grateful for these interactions and his example.

— William Alford, Jerome A. and Joan L. Cohen Professor of Law, director of the East Asian Legal Studies Program, and chair of the Harvard Law School Project on Disability

During several years of the Carter presidency, I worked in the Senate on the Judiciary Committee staff. We worked closely with the White House. And I learned several things about President Carter.

For one thing, he was interested in the judiciary, in part because he was interested in the Constitution. He was interested in the way in which that document has held a broad diverse population together. He was interested in the strength that that document, with its rules and principles, gave to the nation it created. President Carter appointed more than 250 new federal judges, whom we, on the judiciary staff worked to confirm. Those new appointments included me, whom he appointed to the federal appeals court for the First Circuit. And I am grateful.

President Carter was pragmatic. He recognized, for example, that neither pure laissez faire economics nor total regulation of industry was desirable for this country. And we consequently worked together — White House and Senate — to bring about, for example, airline deregulation. The object was to lower prices so that Americans who could not afford to fly would be able to do so. And that happened. By trying to solve economic problems pragmatically, he left more political space open for dealing with problems directly related to basic American values, such as democracy, equality, human rights, and the rule of law.

President Carter did not focus simply upon short term political interests. He appointed Paul Volcker to run the Federal Reserve Board, for example, knowing that doing so might help the nation’s economy but hurt his chances of re-election. He acted on principle. I have tried to follow what he taught — acting on principle — throughout my forty years on the bench.

President Carter was a thoroughly decent man. That is how he thought and acted, both when he was president and in his career afterwards. We are grateful for the good that he has done, for the nation, and, through his embrace of principle, for the world. We mourn his passing.

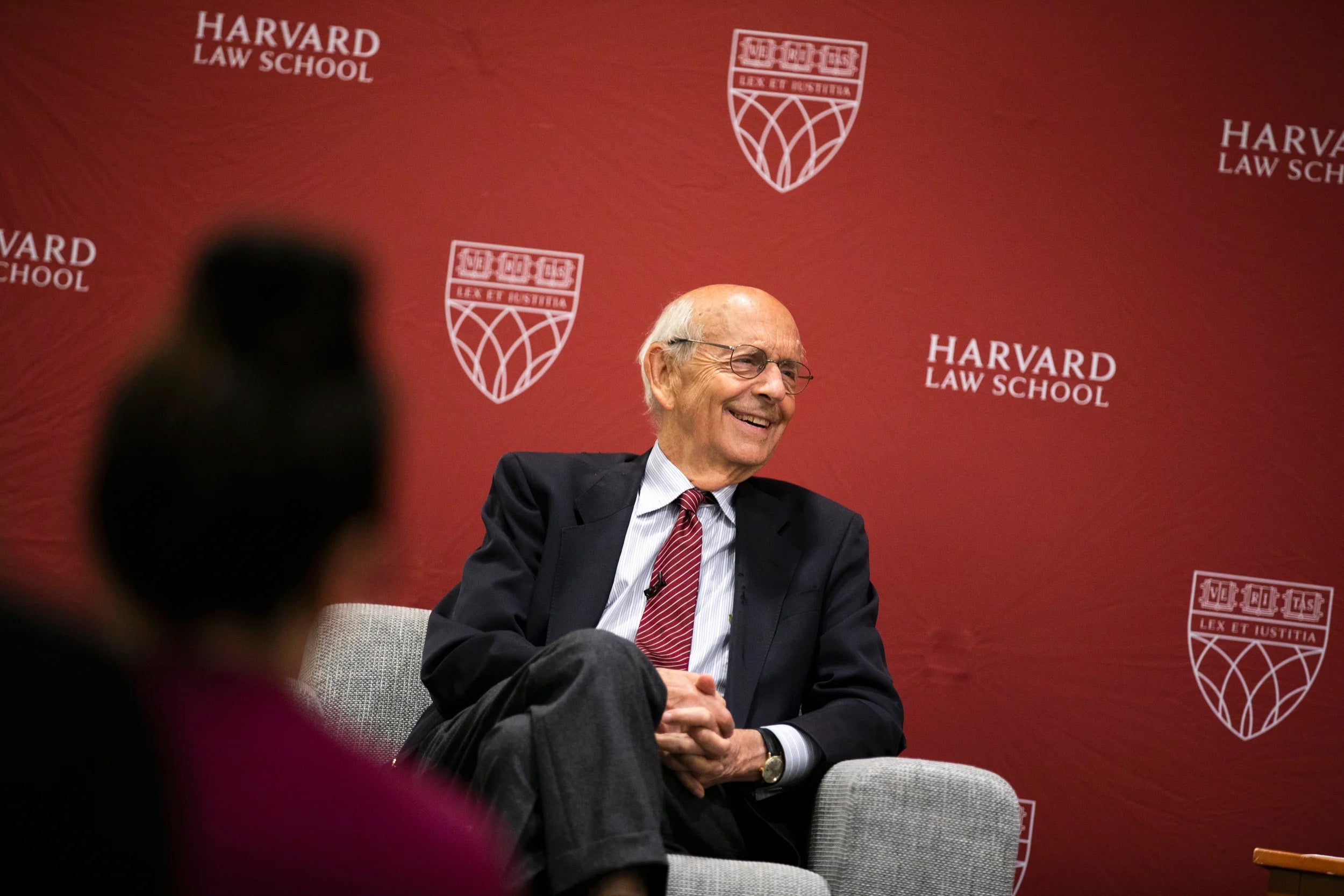

— Stephen Breyer ’64, Byrne Professor of Administrative Law and Process and retired associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

Credit: Stephen Kelleghan

Jimmy Carter’s elevation of human rights in U.S. foreign policy offers many urgent lessons for today. Whatever challenges he faced consistently applying the principles he championed as the 39th president, he made a radical break with decades of foreign policy tradition, changed the world’s understanding of America’s aspirations, showed deep empathy for individuals who had suffered human rights abuse and, in so doing, made a lasting impact on both the United States and the world.

Much of the celebration of Mr. Carter’s legacy has centered on his groundbreaking post-presidential work. Understandably so: Beyond his tireless volunteering, working to build affordable homes with Habitat for Humanity well into his 90s, the Carter Center — his passion for the past 42 years — has worked with USAID and others to nearly eliminate river blindness in the Western Hemisphere and to decrease the number of reported Guinea worm cases from more than three million per year in the mid-1980s to just 14 in 2023. Mr. Carter also changed the global understanding of what a free and fair election requires by pioneering the dispatch of diverse teams of impartial observers, which have monitored 125 elections in 40 countries. And after leaving office in 1981, he lent his mediation services to successive administrations, defusing tensions in such places as Guyana, Liberia and Sudan.

As president, his foreign policy legacy was also consequential. It includes the negotiation of the Camp David Accords, which brought about an enduring peace between Israel and Egypt, and the establishment of diplomatic relations with China (after the rapprochement begun under President Richard Nixon). Mr. Carter also negotiated the Panama Canal treaties and pushed them through the Senate, in that way removing a source of anti-American feeling in Latin America and showing that the United States, in Mr. Carter’s words, would “deal fairly and honorably” with smaller nations.

— Samantha Power ’99, USAID Administrator and former U.S. Permanent Representative to the United Nations

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.