Professor Noah Feldman has a knack for picking the right book topics at the right time.

Professor Noah Feldman has a knack for picking the right book topics at the right time.

He began work on his first book, “After Jihad: America and the Struggle for Islamic Democracy,” long before the topic became of intense interest after the 9/11 attacks. And he started working on his latest, about four of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Supreme Court justices, in 2005, years before the New Deal era suddenly became newly relevant.

“I obviously had no idea we were headed for this big recession we are in or that Wall Street would be the subject of so much criticism or that the parallels with the progressive era and FDR’s presidency would become so central,” Feldman says. “It was just serendipity.”

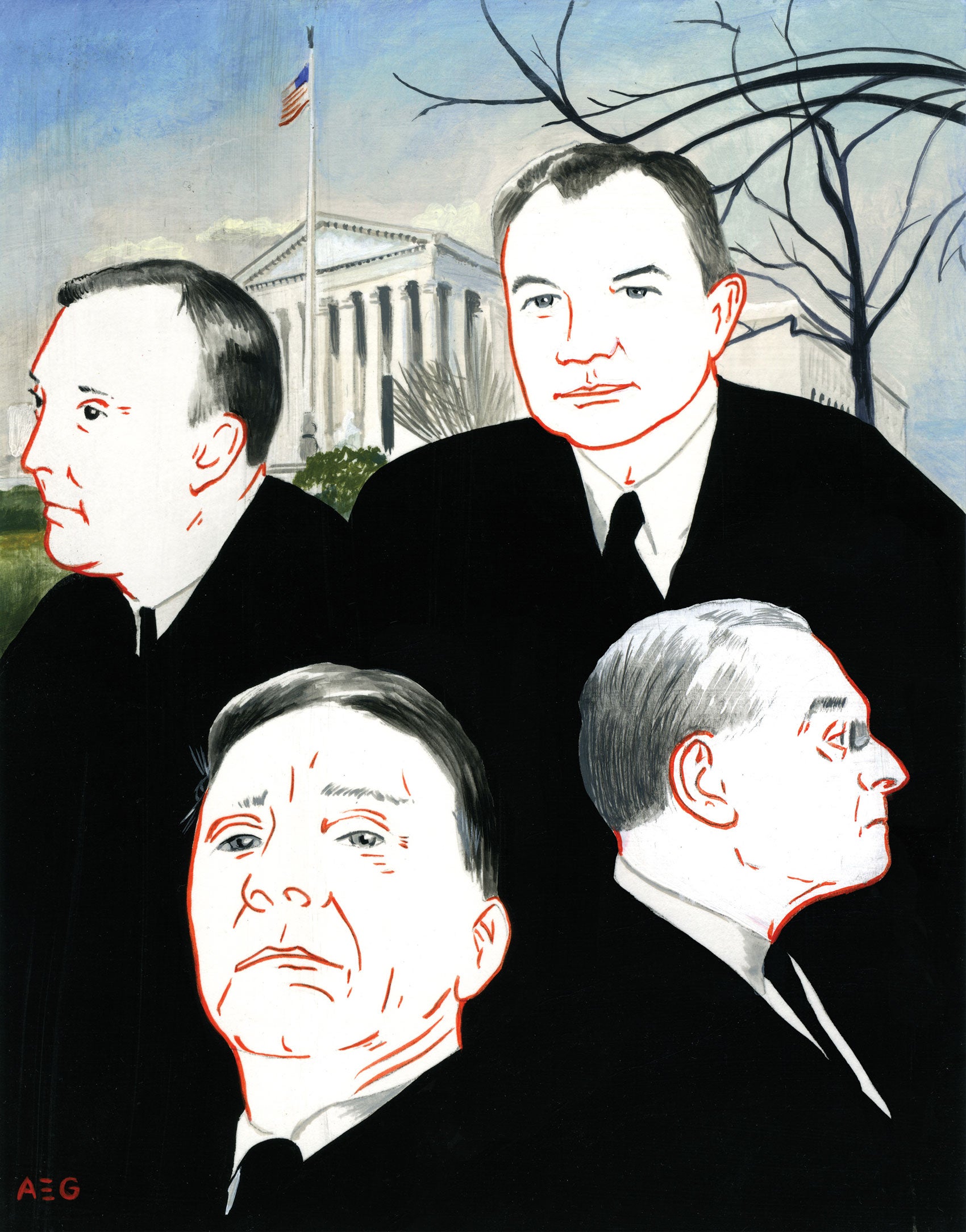

In “Scorpions: The Battles and Triumphs of FDR’s Great Supreme Court Justices,” Feldman focuses on four men with remarkably diverse resumes, who, despite shared links to Roosevelt, often found themselves at odds once they joined the Court.

Related video: Noah Feldman and NPR’s Christopher Lydon discuss the professor’s latest book

While much scholarship has focused on the justices of the Warren Court of the 1960s, Feldman says, “it seems to me many of the most important ideas we think of as our constitutional ideas were actually created in the years of the Roosevelt Court.”

Feldman says he focused on Hugo Black, William O. Douglas, Felix Frankfurter LL.B. 1906 and Robert Jackson because “these four justices were all chosen in an era when life experience was central to getting to be a justice, and they had fascinating life stories and backgrounds which they then brought to bear when they were on the Court.”

Black, an Alabamian and former Ku Klux Klan member, came to the Court directly from the U.S. Senate, where he had a reputation as something of a radical.

Douglas had headed the Securities and Exchange Commission and made a name for himself as a critic of Wall Street.

Jackson had served as Roosevelt’s solicitor general and attorney general during World War II and the president’s most important wartime legal adviser. He later took a leave from the Court to serve as chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg war crimes trials.

Frankfurter, a professor at Harvard Law School at the time of his nomination, had been an important—and often controversial—figure in American liberalism, coming to the defense of Italian-American anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti, who, despite his efforts, were executed in 1927.

“These are people with huge life experiences, and they also had huge personalities,” Feldman says. “They had no judicial experience, but by any measure they are four of the greatest justices we’ve ever had.”

These four interwoven biographies are a change in direction for Feldman, whose last book, “The Fall and Rise of the Islamic State,” traced the history of Shari’ah law. But he says he tends to track back and forth between a focus on the Islamic world and U.S. constitutional history. He says he got the idea for this book while teaching constitutional law.

“I became fascinated with the way different personalities of the justices reflect and create their beliefs and ideas,” Feldman says. “These are real human beings and not just names on a page.”

He details the common ground these four justices shared when they joined the Court between 1937 and 1941 and how their relations frayed in subsequent years as each refined a different judicial philosophy.

But Feldman doesn’t think it’s necessarily a bad thing that they came to dislike each other and argue so much.

“We live at a time when we believe everyone should be collegial—including Supreme Court justices—but these justices made greatness out of their differences,” Feldman says.

Looking back half a century after the quartet served together, Feldman says each of the justices continues to be influential.

He credits Black as an early voice for originalism, Douglas as the “intellectual father of the rights-expanding school of constitutional thought,” and Jackson as the progenitor of the sort of pragmatism adopted more recently by Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and Stephen Breyer ’64, while Frankfurter was the strongest advocate of judicial restraint.

Of the four, Feldman views Frankfurter as deserving more credit than he gets. “Republicans don’t like him because he was a New Dealer, and Democrats don’t like him because he was a judicial conservative,” he says. “But even though nobody practices it, everybody preaches judicial restraint, and that’s Frankfurter.”

Feldman says all four would find confirmation to the Supreme Court hard going today, a reality which he thinks is regrettable.

“There’s something to be said for people with broad life experiences, big ideas and strong personalities.”