At 10 a.m. on Friday, June 26, Evan Wolfson ’83 sat tied to his phone, repeatedly refreshing SCOTUSblog and Twitter.

He was surrounded, as he had been for days, by fellow staff members in a Manhattan conference room at the office of Freedom to Marry, the national advocacy group he had founded in 2003. Suddenly, the news broke. Justice Anthony Kennedy ’61 was reading the majority opinion in Obergefell v. Hodges, the decision holding that same-sex couples have a constitutional right to marry in all 50 states. Cheers erupted and champagne bottles popped open. Wolfson retired to his office to read the opinion in full, and was surprised to find himself in tears. Thirty-two years had passed since he wrote a paper as a student at Harvard Law School arguing for the right to same-sex marriage, and two decades since he had served as co-counsel in the first state case to gain real traction for that right. The legal battle was over. He was finally, gloriously, out of a job.

To call the legal and cultural battle for same-sex marriage Wolfson’s lifework is no exaggeration (presuming that for attorneys, life really begins in law school). At Harvard Law, in his 3L paper—the thesis then required for graduation—he developed an interdisciplinary argument for understanding marriage as a human, individual right guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution to all, including same-sex couples.

Wolfson was not the first to explore this topic. Three years earlier, the Harvard Law Review had published “The Right to Join a Family: Traditional Marriage and the Alternatives,” a student note setting out possible constitutional arguments in favor of same-sex marriage, notably that marriage is a fundamental right that the state lacks a sufficiently important interest to deny. Indeed, Wolfson wrote his paper 10 years after the first cases made their way through American courts seeking a right to marry, and failing to—as in the words of Baker v. Nelson, the only Supreme Court case on the matter pre-Obergefell—present “a substantial federal question.”

While for Wolfson, working on his paper was a personally profound experience melding law, history, culture, and political thought, he was met with mostly benign skepticism and indifference. He needed a faculty supervisor and was turned down by the obvious candidates, professors whose work directly involved issues of family law, constitutional law and even LGBT rights. Some thought the subject too trivial or, as the Baker Court had put it, too insubstantial, to serve as a capstone to three years of law school. Others found the topic not nearly radical enough, as it advocated for a traditional relationship that many feminist thinkers at the time opposed. Finally, Wolfson approached Professor David Westfall ’50, an expert on family law and trusts and estates, who agreed to oversee his work.

Wolfson thought of Professor Westfall as a very “bread and butter” man—not edgy at all. He is sure that the paper Westfall ultimately received was not the one he was expecting—relatively brief in its exploration of law, and sweeping in its engagement with questions of gay history and social change. Wolfson admits he was disappointed to receive a B. Years later, however, he was tickled to read Westfall interviewed about him saying simply, “It’s so refreshing to see a student apply something he learned in law school.”

If they lost Obergefell, they would pick up the pieces and start again. Wolfson was ready for that. “But, boy, was I glad not to have to,” he said.

Observers, including the dissenters in Obergefell, often note that the LGBT movement has seen swift change. Today, HLS’s LGBT student group Lambda boasts more than 100 members. A yearly career fair at the Lavender Law conference draws over 130 law firm recruiters seeking LGBT lawyers.

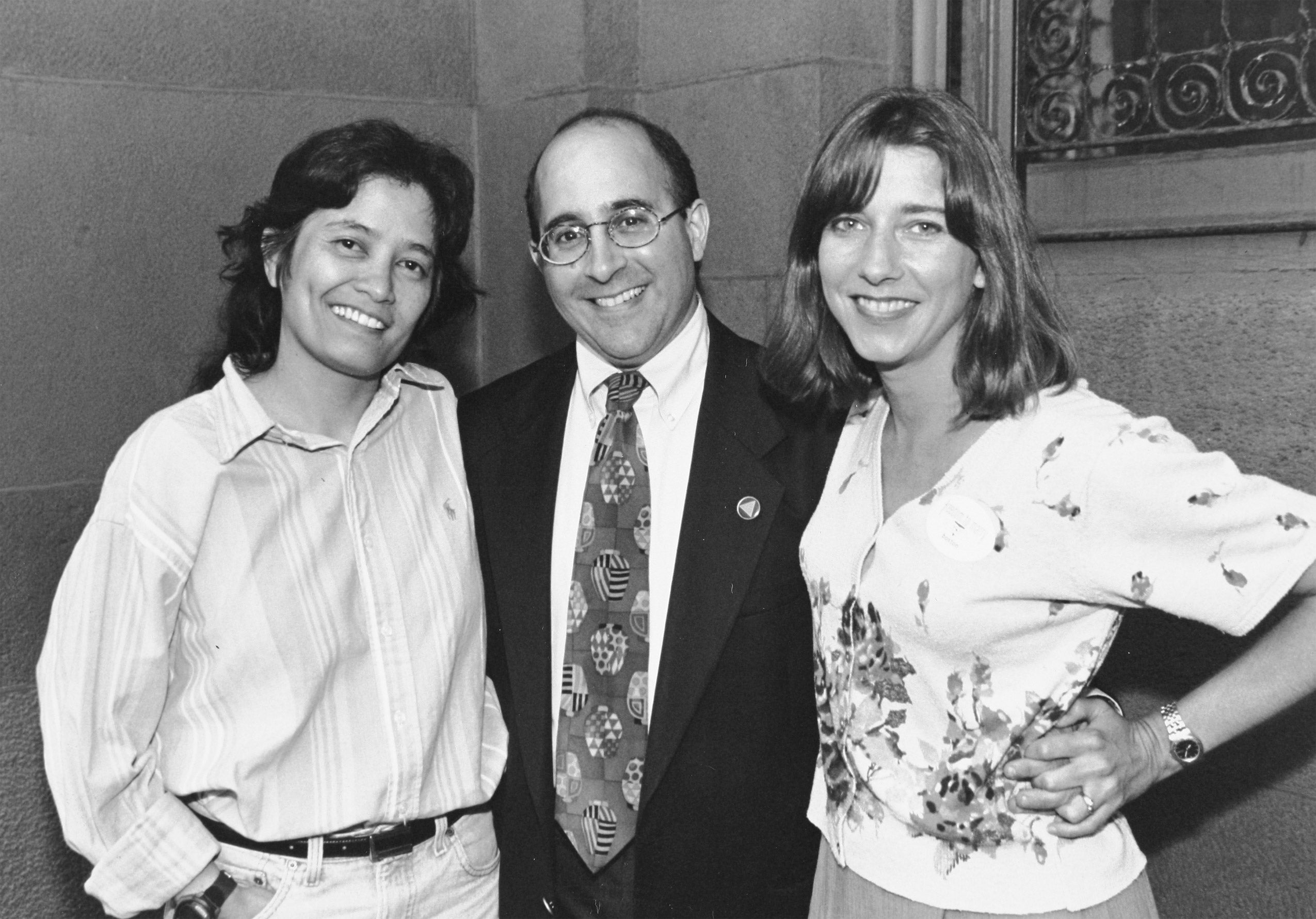

By comparison, in 1981, three years after the founding of HLS’s first LGBT group, the Committee on Gay and Lesbian Legal Issues, or COGLLI, was represented in the law school yearbook for the first time. Beneath the photo of six men and two women, a caption states that the members chose to appear “after careful consideration of the possible personal and professional ramifications, to give expression to the efforts of those who fight unjust discrimination on all fronts, especially with regard to the right to love.” The caption includes no student names. By Wolfson’s third year, a photo appears with IDs—but only a fraction of COGLLI members were pictured, and Wolfson was not among them.

One student smiling in the 1983 photo, however, was Wolfson’s close friend Brian Koukoutchos ’83. He was a double rarity—a student who was willing to be a public face for COGLLI, and a heterosexual member of the group. Koukoutchos felt he was essentially immune from attack, but he remembers walking into on-campus job interviews and being met with hostility. When he asked if there was an issue with COGLLI, the sole extracurricular activity listed on his resume, he faced an uncomfortable silence—and a quick end to the interviews.

In Wolfson’s years at Harvard, COGLLI became increasingly politically active. One project involved questioning employers who planned to interview at HLS about whether they would abide by Harvard’s nondiscrimination policy. And at a time when student identity groups frequently sponsored moot courts, COGLLI joined in with its own, focusing on issues involving LGBT rights.

Wolfson never published his paper, but in 2004, he published a book, “Why Marriage Matters: America, Equality, and Gay People’s Right to Marry,” that drew heavily on themes he had first explored 20 years prior. By then, despite an upswing in support for LGBT rights, he had endured a career filled with painful losses.

After law school, he worked with Koukoutchos, who pursued a career in appellate litigation, and Professor Laurence H. Tribe ’66 on Bowers v. Hardwick, a case that ultimately upheld a Georgia anti-sodomy law. In 1986, he sat in the audience of the Supreme Court’s oral arguments, holding hands with Koukoutchos and Michael Hardwick, the ultimately losing plaintiff, as Tribe faced questions from the justices comparing sodomy to incest and bigamy.

In 1996, Wolfson and the movement enjoyed a brief win when a Hawaii lower court held, in Baehr v. Miike, that the state had no rational reason to deny marriage licenses to same-sex couples under the state constitution, only to fall back again when Hawaii passed a constitutional amendment to prevent same-sex marriage and the U.S. Congress responded with the Defense of Marriage Act. In 2000, Wolfson argued before the Court in Boy Scouts of America v. Dale, in which the Court ultimately decided that the Boy Scouts had a First Amendment right to exclude openly gay men.

Fifteen years later, as Wolfson sat in his office—months away from finally shutting its doors for good—reading the Kennedy opinion, he was flooded with memories of conversations he had had over the years with the pioneers of a right to marry, the men and women who had brought cases throughout the ’70s and ’80s. They laid the groundwork for him and for other advocates such as Mary Bonauto, the movement’s lead lawyer in Obergefell. Everything they had been arguing for—the language of dignity and core, basic humanity—appeared on the screen before him in the majority opinion. At first, he thought that was what had made him so uncharacteristically emotional. But mostly, he realized afterward, he was relieved.

For decades, Wolfson had been Mr. Marriage (he was married himself, to Cheng He, in 2011). Wolfson never doubted that the marriage movement would eventually prevail, but it was easy to overlook, on such a jubilant day, how many losses the movement had suffered on the way. On the darkest of days, he would rally the troops and make speeches about moving forward. He knew that if they lost Obergefell, they would pick up the pieces and start again. “I was ready for that if I had to do it,” he said. “But, boy, was I glad not to have to.”