On May 14, 1874, for the first time, an intercollegiate “foot-ball” game, as Harvard’s Magenta newspaper called it, was played on what is now the Harvard Law School campus, on Jarvis Field near where Langdell Hall now stands.

The Crimson emerged victorious over McGill by a score of 3-0. A rematch the next day, played under rugby rules, ended 0-0. The rules of football were very much evolving, and Harvard followed “Boston rules,” closer to those of soccer. But after these matches with McGill, the Crimson incorporated elements of the game as played by the Canadians (running with the ball, downs, and tackling) into their first intercollegiate match with Yale in 1875, helping to shape football as it is played today.

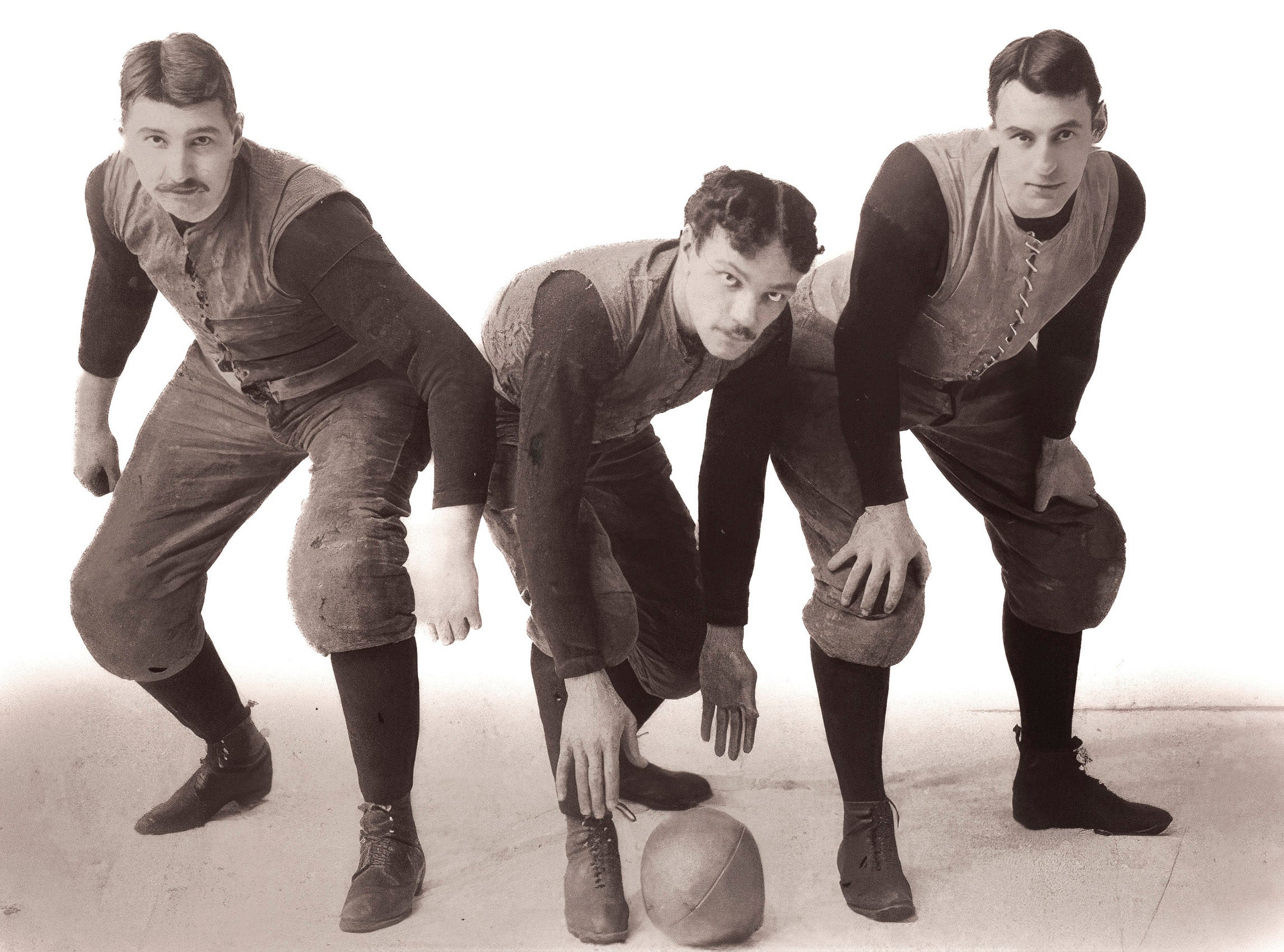

Less than 20 years after that doubleheader, William Henry Lewis LL.B. 1895, then a student at Harvard Law School, played football for two years for the college’s team (which eligibility rules then allowed), after having played as an undergraduate at Amherst. He was named to Walter Camp’s All-America team, the first Black player to receive that honor. He coached Harvard’s team for 12 seasons after he graduated, and he wrote one of the first books on the game he loved, “A Primer of College Football.” According to a 2005 profile of Lewis in Harvard Magazine, he continued to practice law much of that time, even serving as assistant U.S. attorney for Boston, a first for Black lawyers. He later served as assistant attorney general of the U.S. under President William Howard Taft (then the highest federal position ever held by a Black person). He was also a criminal defense attorney, heading one of the most successful practices in Boston.

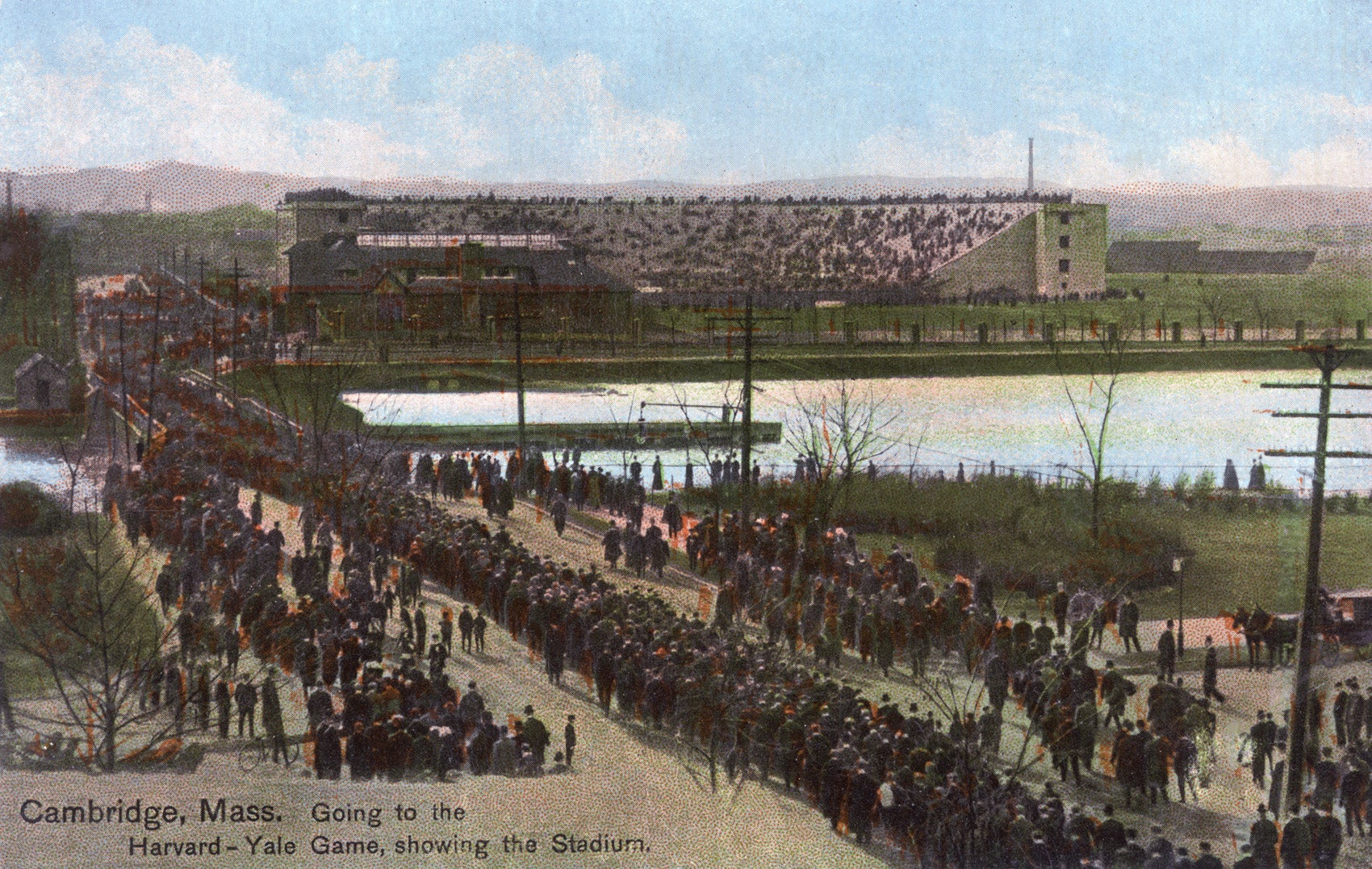

Even when intercollegiate matches were no longer being played on Jarvis Field after the construction of the Harvard Stadium in 1903, football, and in particular the Harvard-Yale game, continued then, as it does today, to play a role in the lives of students on the Harvard Law campus

That was true even for those who did not attend. The letters home of two HLS students that are part of the school’s collections attest to that fact. When he was a law student, Austin Wakeman Scott LL.B. 1909, who went on to be a professor at the school, wrote to his mother that although there had already been a “good deal of talk about the Yale game,” he wasn’t very interested, owing to his inability to “get quite enough spirit into the ‘Rah Rah Haavards.’” Student Albert Burt LL.B. 1914 wrote to his younger brother that following a Harvard win in New Haven, his fellow students returned to the dormitory “almost wild” with plans for “getting out and waking up the hall.”