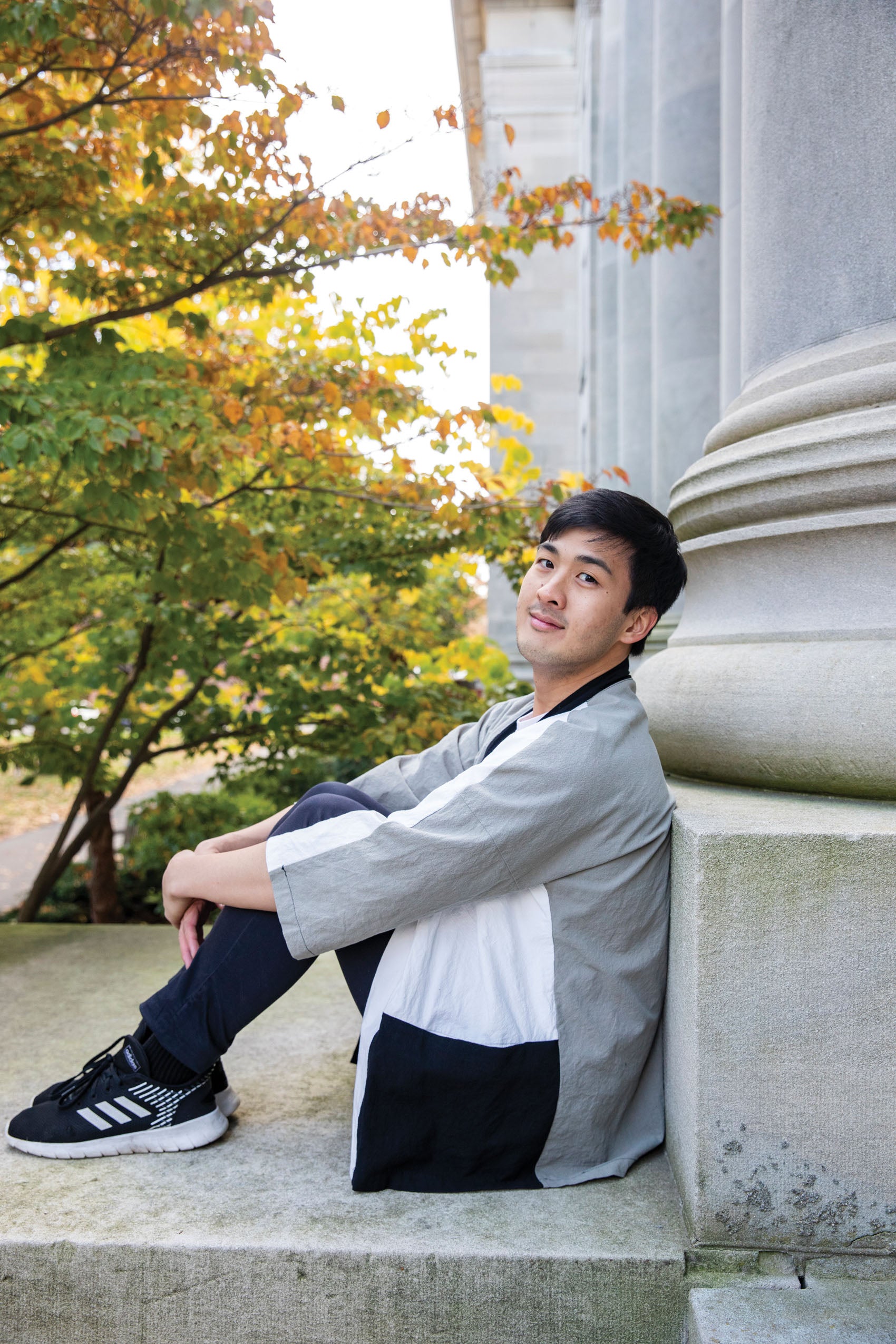

Julian Morimoto ’21 was born and raised in Honolulu, where he shared a two-bedroom apartment with nine family members including his mother, a waitress, and his stepfather, a cook. He sometimes studied in the stairwell because there was no other space, and the neighborhood could be violent. “A lot of people have the impression that Hawaii is this really magical place, but if you’re not rich or if your parents aren’t well connected, the Hawaii you live in is different,” says Morimoto.

As he headed to Harvard Law School, Morimoto says he really wanted to make sure he could find a space where he “could share these experiences and be around people who could understand them better,” and with whom he could bond. A new student organization, First Class, is the space he sought.

First Class was launched in the winter of 2017-2018 by Li Reed ’20, Ariel Ashtamker ’19, and Richard Barbecho ’19, who saw a need for support, community, and advocacy for first-generation college and/or low-income students. (It followed on Supero, a similar organization started several years earlier.) First Class holds monthly dinners and an annual welcome dinner; advocates for tailored programming at the law school; and supports members in their career aspirations. The organization currently has about 160 members.

“I think the most important thing was creating community for a group of people who otherwise didn’t have an easy way to connect with each other,” says Reed, the 2019-2020 president of the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau, who, like many in First Class, describes herself as both first-gen and low-income. “Being from a low-income family or being a first-generation student is not a visible affinity group,” she says, yet these students often face similar challenges, from seemingly small things, like not being able to connect socially with section mates due to budget constraints, to not having lawyers in the family to ask basic questions about the profession.

The organization exists to serve its members, its board members emphasize. About 40 to 50 students attend each monthly dinner, which—like all of First Class’s events and services—is free. The dinners are also a time when students can get information about things they may be unfamiliar with, such as how to compete for the Harvard Law Review or a position at the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau, says Morimoto, who this year serves as co-executive director.

Last year, First Class created a “Low-Income Survival Guide,” which provides tips and resources to help students from low-income backgrounds navigate the financial demands of law school and life in the Cambridge area—everything from strategies for finding affordable housing in Cambridge to information on scholarships and financial aid. (HLS provides tens of millions of dollars in financial aid annually, all of it need-based, and is one of only two law schools in the country to provide 100% need-based aid.)

First Class members also successfully advocated for the elimination of the minimum borrowing requirement for need-based grant recipients. Changes the school has made to its policy now allow students who reduce their living expenses to also reduce their student loans.

First Class is also looking to create a fund to assist students in purchasing clothes for job interviews. The organization has worked with the Office of Career Services and the Office of Public Interest Advising to develop programming tailored to first-generation and low-income law students, such as presenting them with options if a student can’t afford to travel for a job interview.

“People seemed to have some kind of rule book … you don’t have access to.”

Joey Bui ’21

The HLS administration was strongly supportive from the start, says Reed. Mark C. Jefferson, assistant dean for community engagement and equity, a first-generation college student who graduated from the University of Michigan Law School, has been a force behind starting and supporting the organization, and he was the keynote speaker at this year’s First Class welcome dinner in August.

“Enter Harvard Law School with your whole self, and explore each and every thing this venerable place has to offer,” said Jefferson in his keynote. “Everything here is just as much yours as it is anyone else’s, and don’t allow anyone to convince you otherwise.” He received a standing ovation.

HLS Dean John F. Manning ’85 and Professor I. Glenn Cohen ’03, faculty director of the Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics, are also first-generation students, and both have spoken at the First Class welcome dinners that are organized by the Dean of Students Office.

“I remember what it was like to arrive here as the first in my family to graduate from college and the first to go to law school,” says Manning. “I was thankful to be able to learn from other students as I figured things out. I’m very grateful to First Class members for all they do.”

“Neither of my parents finished high school,” says Cohen. “I couldn’t be prouder of or more grateful to them, but as with many first-gen students, I definitely felt there was a steep on-ramp to law school as a result. I’m so glad the students and administration have supported this effort to make the law school more welcoming to first-gen students.”

Joey Bui ’21 is the daughter of Vietnamese refugees who lived in refugee camps after the Vietnam War before they immigrated to Melbourne, Australia, where Bui was born. After attending NYU Abu Dhabi on full scholarship, Bui, the first in her family to go to college, decided to become a lawyer and headed to Harvard Law School. When she landed on campus, she felt that, in terms of navigating legal education and the profession, “people seemed to have some kind of rule book or outside resources you don’t have access to,” she says. By connecting with other students in First Class, “I felt so much better because I was really dreading that I would be a fish out of water,” says Bui, who is this year’s co-executive director with Morimoto.

Juan Espinoza ’21, whose parents are farmers and in the service industry in Palm Springs, California, says, “Not many of my peers here understand what it means to be working-class.” He joined First Class because he “was looking for community,” he says, for students who would understand “what it means to be low-income at an elite institution.” Before he chose HLS, Espinoza attended a reception for Latinx students at another Ivy League law school, where a student mentioned that his aunt and uncle were justices in the Venezuela courts. “That’s very different than to say, ‘My parents are farmers or in the service industry and have never gotten a formal education,’” says Espinoza, who is studying law in order to analyze power structures that maintain systems of poverty and disenfranchisement.

Even though First Class is growing, student outreach presents a bit of a challenge, Bui says. “Some people may not want to be known as low-income, and we want to respect that as well even though we hope some people will find pride in growing up in low-income backgrounds and being able to make it here,” she says. And, she adds, while each student’s personal history informs who they are, “now that we’re at HLS, we are extremely privileged people. The question is, What are we going to do with that privilege?”