“How Change Happens,” by Professor Cass R. Sunstein ’78 (MIT)

A single person cannot change a social norm; it requires a movement from people who disapprove of the norm, writes Sunstein. He explores how those movements, ranging from the fight for LGBTQ rights to white nationalism, take shape and effect change. Laws, such as those against sexual harassment, can change norms, as can “nudges,” which allow choice but influence people to make changes, such as adding warnings to cigarette packages to discourage smoking. People generally don’t speak out against norms, or they may even falsify what they believe in order to show adherence to them, he writes. But when people live with norms they don’t like, conditions are ripe for change—for good or for bad.

“How Finance Works: The HBR Guide to Thinking Smart About the Numbers,” by Professor Mihir A. Desai (Harvard Business Review Press)

Desai, who is on the faculty at Harvard Law School and Harvard Business School, has taught finance for years to students with a variety of backgrounds. Now he applies his methods in a book aiming to provide readers “with the most central intuitions of finance so that you will never find finance intimidating again.” He begins by delving into the expanse of figures that can make finance intimidating, explaining the ratios and numbers that make up a company’s balance sheet. Other chapters cover entities that make up the financial system, such as hedge funds and investment banks, and the art and science of company valuation. He also shares the perspectives of CFOs and investors to show how the lessons are put into practice.

“The Knowledge Economy,” by Professor Roberto Mangabeira Unger LL.M. ’70 S.J.D. ’76 (Verso)

The knowledge economy, which Unger defines as the “accumulation of capital, technology, technology-relevant capabilities, and science in the conduct of productive activity,” has the potential to dramatically increase growth and reduce inequality, he writes. Yet it has been confined to few workers under the control of elites, which he contends has been a cause of economic stagnation since the 1970s. To facilitate a more inclusive knowledge economy, he proposes a movement focused on changes in education, culture, and politics, which he writes will fulfill “the promise of a better chance to live larger lives and to become bigger together.”

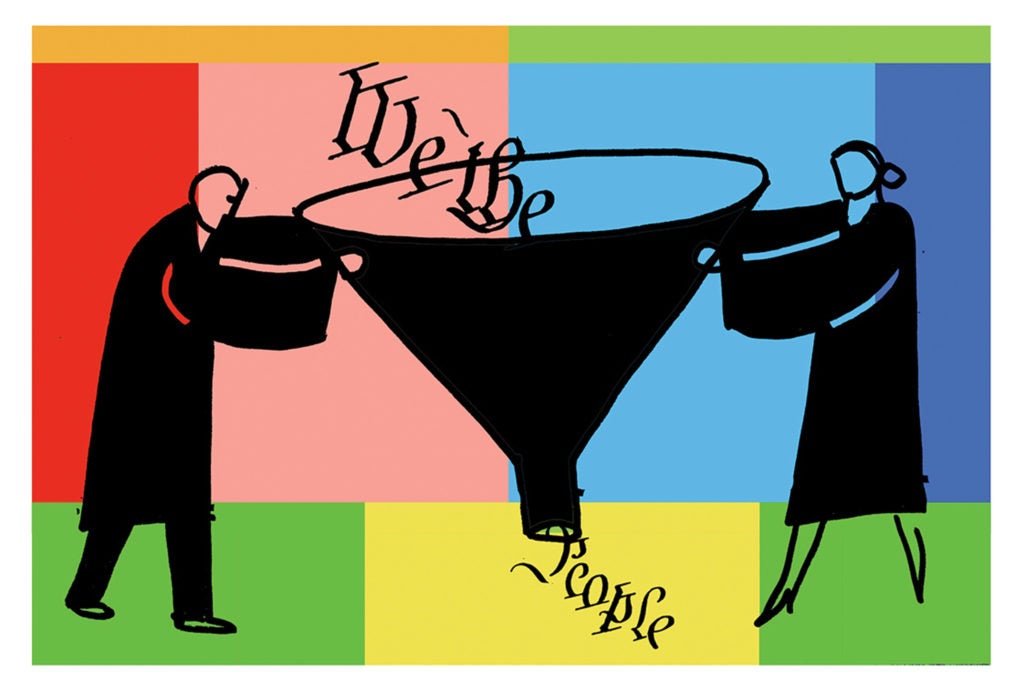

“The Nature of Constitutional Rights: The Invention and Logic of Strict Judicial Scrutiny,” by Professor Richard H. Fallon Jr. (Cambridge)

According to Fallon, we can’t understand what constitutional rights are today without understanding strict judicial scrutiny, which was developed in the 1960s. To pass this judicial test, legislation would be constitutional only if it were “necessary” or “narrowly tailored” to promote a “compelling government interest.” In his book, he examines the emergence of strict scrutiny and how it has applied to cases, including the flag-burning case Texas v. Johnson. Fallon supports aggressive judicial review, he writes, because “government ought not be able to act in ways that either the legislature or a reviewing court believes incompatible with a commitment to ensuring and enforcing a robust scheme of rights against the government.”