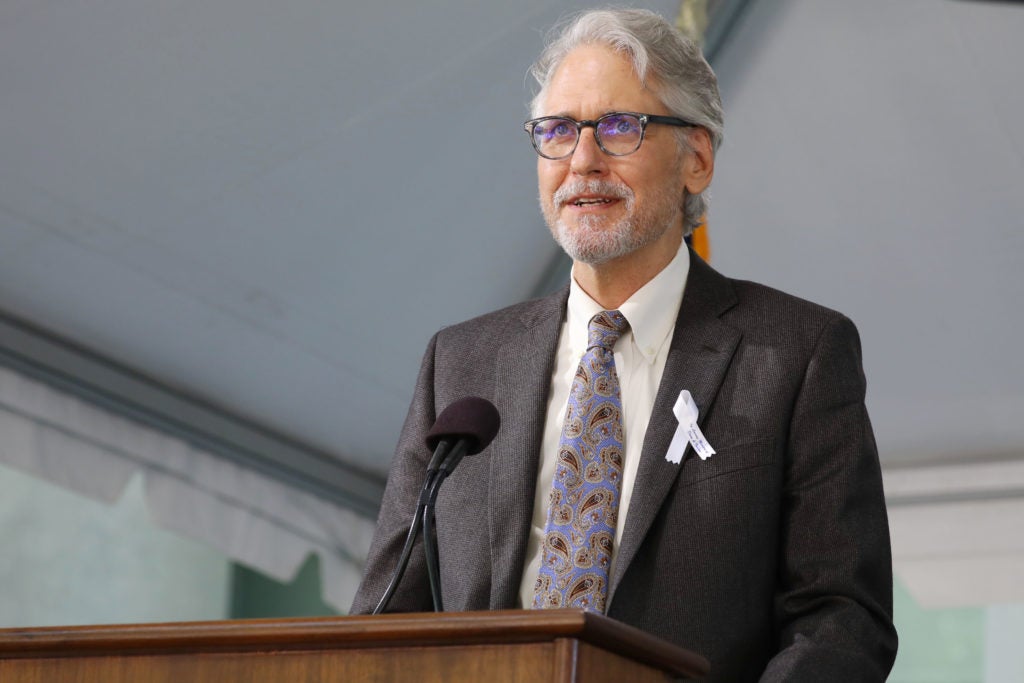

The Class of 2022 made Professor Jon Hanson a four-time Sacks-Freund Award winner at Class Day this week. Hanson was previously honored with the same award, which recognizes teaching ability, attentiveness to student concerns and general contributions to student life, by the Classes of 1999, 2011, and 2015.

“The Sacks-Freund Award is truly the greatest honor of my career. The fact that I’ve received it before does not mean that it was any less shocking, or any less of an honor to receive it, especially from this amazing class,” he told the graduates. “As someone whose life was transformed by teachers — including my fourth-grade teacher, who happened to be my mom — I consider teaching to be a calling, my way of giving to the world. It means more to me than you can know that you find it valuable.”

Hanson said he originally planned a more upbeat acceptance speech, but recent national events made him reconsider. “I must confess that my unbounded admiration and joy for this class has been mingling over the past few days with my angst about our world. It’s led me to compose remarks that are more sober and earnest, and a bit longer, than I intended.”

Continuing a thread from a Last Lecture he delivered last month, Hanson pondered the nature of justice and the goals of the legal profession — and warned graduates that those two goals can too easily diverge. He singled out a particular challenge that often confronts lawyers as they strive to uphold justice while making tough decisions. “It is predictable that you will feel both fatigue and futility as you struggle to do good and make your work meaningful in a legal system that has too often facilitated, ignored, and normalized injustice. … Eventually, you may even find yourself hating justice every time some young person or old professor invokes it.”

If the concept of hating justice seemed farfetched, Hanson cited the example of U.S. Supreme Court Justice and 1866 Harvard law graduate Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. Holmes, he said, often disparaged the idea of justice while on the bench, including during a conversation he once had with his friend, Judge Learned Hand 1896. When the latter greeted Holmes with an entreaty to “do justice, sir!,” Holmes shot back, “That is not my job. It is my job to apply the law.” Hanson found particular meaning in this statement. “It seems Holmes saw law and justice as mutually exclusive, and justice as completely irrelevant.”

Holmes’ reverence for the rule of law may seem admirable, but Hanson believes the concept is flawed in several ways. First, he noted that the law, strictly applied, has often produced injustice, citing statutes that authorized and fostered the institution of slavery as just one example. “The rule of law loses its appeal when the laws themselves are unjust,” he said. He also suggested that the rule of law is illusory. “As most law students discover in 1L, there really is no ‘rule of law,’ no ultimate source of determinate legal answers within the law.”

Like Hand and Holmes, Hanson stressed that the graduates are likely to face tension between their ideals and legal realities. “Legal staging, legal costuming, and legal thinking combine to render lawyers and judges but cogs, excusing the humans occupying those roles from any sense of responsibility for their choices. … By professing allegiance to fixed laws — ‘The law made me do it!’ — judges have found psychological sanctuary in the affirming claim of disempowerment.”

This is exactly the wrong time in history for that kind of cynicism, Hanson said. “You are an extraordinary class living at an extraordinary time. In light of injustices too obvious, too raw, and too ubiquitous for me to name, there has never in my lifetime been a more vital need for a group of justice-loving lawyers to get busy. In closing, he urged the graduates to heed the advice of Judge Learned Hand that Holmes chose to ignore: “Do justice, Class of ’22, do justice!”