An Iranian lawyer, already an envoy of sorts, hopes to make it official

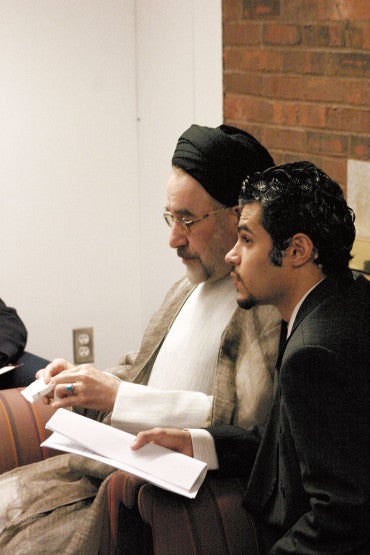

Last fall, when most new LL.M. students were just settling into their studies in Langdell Hall, Sajjad Khoshroo ’07 found himself on the other side of Harvard Square—and in the middle of a political demonstration. As Mohammad Khatami’s personal assistant and interpreter, he accompanied the former president of Iran to a conference at the John F. Kennedy School of Government.

Khatami’s trip—the most significant diplomatic visit since the United States and Iran severed relations in 1980—caused a stir. Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney ’75 refused to give him state police protection, calling him a “terrorist.” Two hundred anti-Khatami protesters lined up outside the Kennedy School, chanting “Shame on Harvard.”

What most of the protesters didn’t know, says Khoshroo, was that Khatami—an advocate of dialogue with the U.S.—was facing just as much criticism, if not more, from the new conservative administration in Tehran.

The son of a career diplomat, Khoshroo grew up fluent in English and Farsi in Tehran, New York and Canberra, Australia. He worked as an English-language journalist while earning his law degree in Iran, writing on the oil and gas sector, and attracted Khatami’s attention in early 2006, shortly after the president left office. “I was asked if I was interested in accompanying him on his travels and writing his speeches in English,” he recalls. “There was an element of trust because of my father’s position.”

Soon, Khoshroo was interpreting for Khatami in New York; Doha, Qatar; and Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. He translated during Khatami’s meetings with Archbishop Desmond Tutu and former U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan. He continued working for Khatami even after enrolling at HLS, where he focused on international finance—and on his country’s future.

In spite of international sanctions and internal obstructionism, says Khoshroo, “I think any change in Iran has to come from the Iranian people.” He is optimistic about their desire for progress, citing Iran’s thriving blogging community. “There’s a booming online culture, especially in the cities,” he says.

As for U.S.-Iranian relations, Khoshroo says a large majority of Iranians favor normalizing ties with the U.S., but he believes that matters weren’t helped in 2002 when President Bush labeled Iran part of the “axis of evil.” At the time, Iran’s nuclear program had been suspended and the country had been helping with the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan. “The comment came out of nowhere,” he says, “and insulted all Iranians.”

At the Kennedy School last fall, Khoshroo met Michael Gerson, who wrote the “axis” speech for President Bush. “I introduced myself,” Khoshroo remembers. “I said, ‘I am from an axis-of-evil country. This is who we are. We are these evil people you talk about.’” Gerson said the phrase was aimed at the Iranian government, not its people. Khoshroo replied that the same distinction could be made when Iranians refer to “the Great Satan.”

“In either instance,” Khoshroo says now, “you can’t use that kind of language. It’s not progress.”

Khoshroo believes that Islam will continue to dominate Iran’s political landscape, but he predicts that a more modern, liberal interpretation of the Quran will ultimately prevail.

He worries, though, that hard-liners may cause younger, reform-minded Iranians to become disenchanted with politics: “If they don’t vote, then the conservatives will continue to win.”

Hanging in the balance will be Khoshroo’s hopes for a political career. “I would love to be Iran’s first ambassador to the United States since the revolution,” he says. “That’s something I would love to do for my country.”