Mayor Anthony Williams steps out, digs deep, shapes up, takes pride, and takes charge on the streets of Washington, D.C.

Wednesday, July 11: It is barely 9 a.m. in Washington, D.C., and a crowd has already formed in a room on the tenth floor of Judiciary Square, the District’s equivalent of city hall.

Mayor Anthony Williams ’87 has called a press conference to announce the selection of his new chief of staff. Nearly 100 people have gathered, more staff than press. This cheery, talkative crowd greets Williams as he steps into the room, shaking hands and smiling on his way to the front.

Dressed in a dark gray suit, crisp white shirt, and his trademark bow tie in blue and white, Williams steps to the podium and simply stands in silence. He might as well have blown a whistle; the room instantly comes to attention.

Williams then proceeds to acknowledge the presence of various political allies and staff, the city council, the local Democratic committee, and his family, including his mother, the “First Lady of the District.”

“To everyone else here, if I haven’t recognized you by name, consider yourself recognized,” he says to light laughter.

Speaking without notes, Williams talks of the District’s improving financial situation. He says his new chief of staff, Kelvin Robinson, has the “best skill set” to work productively with the city council, a group that Williams is known to clash with on a regular basis. What he says next hints at the heat he took for hiring Robinson, a Florida transplant, over a local official. “In a perfect world, we’d have [those skills] in a person who’s been in D.C. a long time, but it’s not a perfect world.”

Credit: Steven Rubin Williams shovels dirt during a ceremony to mark the construction of a new retail center that will bring 800 jobs and more than $5 million in tax revenues to Washington, D.C.

It’s not an apology. Williams is, by now, used to controversy and the criticisms that come with what he will tell you are tough policies and decisive action. Since taking office in the District in January 1999, Williams has streamlined city services, reduced the bloated municipal payroll left by his predecessor, Marion Barry, and held all city agencies publicly accountable for improving budgets, services, and systems. He’s led the District out of receivership–one of Barry’s legacies–with full control of the city’s finances to be returned to the city council this fall. He’ll also take credit for improving school facilities and teaching programs, increasing the number of affordable housing units, and attracting significant commercial investment in the District’s poorer neighborhoods.

“I have this saying, that James Brown is the hardest working man in show business, and I’m the hardest working man in the country,” Williams says later in the day, in a conversation with the Bulletin. “I’m not entitled to this; I don’t have any grant to do this. Every day I’m doing this is really a privilege and an honor, and I’ve got to maximize my time in it.

“That’s why I’ve taken a lot of tough stands,” he continues. “I actually don’t consider losing the next election to be the worst thing in the world. I mean, I can live another life. I think that’s a healthy attitude. I’m totally subservient to the people that I work for–the citizens. I work for them and they’re the boss. I’m not saying I’m some saint or something. But I believe that there are certain key decisions where you have to stand up and be counted, and be willing to take short-term pain for long-term gain.”

Privatizing the District’s public hospital, D.C. General, was one such controversial decision. Another was moving the city’s school board from an all-elected board to one that is partly appointed. “I’m proud of that,” he says. “That took an enormous amount of work.”

Back at the press conference, Williams wraps up his remarks by quipping, “I’m not going to be like Fidel Castro, who passed out after a two-hour speech. I’m going to stop now.” He likes this joke, according to one of his press assistants, and he’s likely to use it again in another speech, maybe today, maybe later this week. Then he’ll find another joke and start all over.

The mayor’s next stop in this tightly scheduled day is a huge empty lot in the District’s Brentwood neighborhood, where a car impoundment lot is being transformed into a major shopping center, anchored by retail behemoths Kmart and Home Depot and the supermarket Giant Food. Though backhoes and dump trucks are already chugging around, preparing the site for construction, Williams is holding a groundbreaking ceremony to mark this major economic victory for the city.

While crews hurry to erect a stage and podium, a strong hot breeze toys with their progress, tipping flagpoles and unfastening corners of store banners. They are running a little late, and a member of the security team radios ahead to the mayor’s official SUV to tell the driver to take a detour, so he won’t arrive before everything is ready.

Area residents gather quickly in the lot, as do TV crews from three local stations. Members of the press mix with staffers they clearly know well. Employees from other Home Depot and Kmart stores collect in clusters of orange aprons and blue shirts. A handful of photographers mills about in a crowd that has ballooned to nearly 200 people when the mayor arrives to join the half-dozen other city officials, store representatives, and Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton on stage.

This is the mayor’s chance to bask in the fulfillment of a promise he made in his campaign–to boost economic prosperity to every ward of the District. The Home Depot on Brentwood Avenue will be the first ever inside the beltway. According to the mayor’s office, the retail center will bring 800 jobs and more than $5 million in tax revenues to the District, reversing what Williams calls the “hemorrhage of retail dollars out of the city.”

When the speeches end, the crowd follows Williams and the others to a pile of newly arrived soil for the requisite photos. Standing shoulder to shoulder, each with a shiny new Home Depot-issued shovel in hand, the officials take a swipe at the dirt while grinning brightly for the cameras. Williams hams it up, shakes hands with his constituents, lets them snap their own photos of him. All around them, the din of construction already under way seems to punctuate a sense of action and effectiveness that Williams personifies. Things are happening now, not next year. Now.

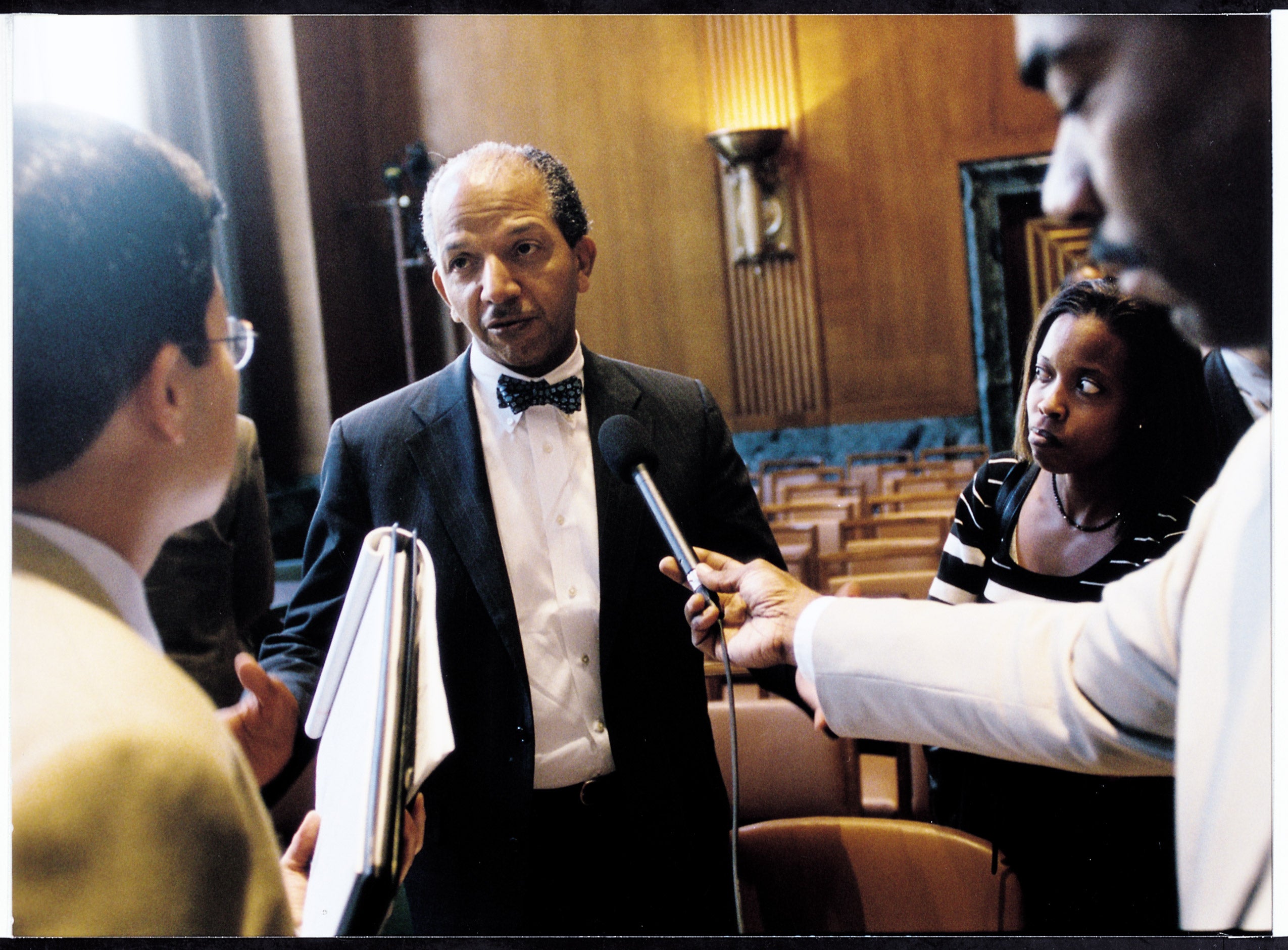

Credit: Steven Rubin Williams testifies before a U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations subcommittee. The federal government approves the budget of Washington, D.C.

Williams knows he’s having an impact on D.C. because he goes to great lengths to measure it, through a system of performance management that is rarely applied so rigorously in the public sphere. To help his staff and city agencies set and reach goals for service, he developed a citywide “strategic scorecard” program that spells out specific objectives. At the end of a defined time period, a scorecard is issued to the public that reports on whether each goal has been met. Williams has not been afraid to say what hasn’t been achieved and talks often about how the scorecards can help officials to learn and adjust efforts.

He also isn’t afraid to hear directly from residents and keeps a close eye on the comments that come through a dedicated hotline.

“You know you’re doing a good job because the complaints change,” he says. “The character of the complaints tells you that you’re improving. For example, if people were telling me there was a homicide down the street, some car was blown up, or just that there was serious crime on the street and the neighborhood was in mortal danger, that’s one set of problems. If people are complaining about trees not being trimmed, or that we’re not putting up signs quickly enough, or that phone calls aren’t returned quickly enough–you know you’re making progress. If you know where we’ve been in this city, going from bankruptcy to now, that tells you you’re making progress. People aren’t going to say you’re doing a great job, they’re going to always point out what more you need to do.”

Williams–who rose to prominence in the District as the maverick chief financial officer hired in 1995 by then-mayor Barry and proceeded to publicly criticize his boss’s management and fiscal activities–easily slips into a comparison of then and now.

“There’s a tremendous amount of faith in what I can do,” he says. “When Marion Barry was just about ready to leave, and the control board was in, and things were at their worst, we’d have a community meeting and there’d be five or six people there. No one bothered to come at that point. Now we can have meetings with 500 or 600 people. That’s a sign that people have a high level of expectation, and if we can deliver on that expectation, that’s a tremendous achievement.”

Healthy Living

The next stop for Williams is Freedom Plaza, an elevated concrete park between 13th and 14th Streets along Pennsylvania Avenue, NW. He arrives to find a long line of people waiting outside a white tent marked with signs offering free screenings for blood pressure, diabetes, and cholesterol. It’s just after 11 a.m., but already the sun has taken over the unshaded square, though its usual burn is tempered by the same strong breeze.

Credit: Steven Rubin Williams touts fitness efforts at the Mayors’ Health Challenge in Freedom Plaza.

Williams wastes no time in taking his place at a microphone set to one side of the tent, and a crowd of local newspaper photographers creeps forward for the best shots. This is another event in the Mayors’ Health Challenge, an ongoing program to promote positive health habits among residents of the District and other cities. Though he holds a set of notes, Williams speaks more often extemporaneously, warmly inviting citizens to join him in good diet and exercise habits. “Twenty-two percent of adult District residents have high cholesterol,” he tells the crowd. “And 50 percent of folks in D.C. are overweight; 20 percent of them are obese. Real health care is preventative care. What you’re doing here through these screenings, you’re doing for yourselves.”

The speech is quick and to the point: Williams wants his city to take responsibility for its health. He tells a local news station afterwards, “What we win in the health challenge besides better health is a better economy. We save money when less people are sick, and we can prevent needless loss of life.”

Williams spends nearly 25 minutes at the fair, shaking hands and talking with residents, before slipping away from the crowd to check his e-mail pager for messages. For a half-second, he appears to stand alone at the edge of the square, just another businessman. But Williams is never alone on the job. He is constantly surrounded–though at a respectful distance–by a handful of security agents, each dressed neatly in business attire with mirrored sunglasses and a telltale wire tucked behind one ear.

As Williams clips the pager back to his belt, Tom Sherwood, a correspondent for the NBC affiliate in D.C., steps forward with a microphone and a cameraman to ask Williams about his earlier announcement on the new chief of staff. Williams listens intently to Sherwood’s inquiry and then looks down at the pavement for a moment to gather his thoughts before answering. The exchange is done in five minutes, and Williams and his entourage move quickly to his waiting SUV. In the next minute, they pull away, headed to a luncheon with local education officials.

Though this day is busier than most summer days for Williams and his staff, downtime can be hard to come by even on a slow day. For someone who is not naturally outgoing, Williams has carefully honed an ability to be “on” for long days in public life. “I’m reserved and not automatically a hugging type of person,” he says later in the day. “But everyone brings a skill set to the job, and what you try to do is leverage your real skills and cover for your weakness. Unless you’re blind, you recognize your weaknesses and you cover for them in your life and your job.” He shares the reserve of his father, who, Williams says, “made about three or four phone calls his entire life. But in this job, not really liking to be on the phone is not the best attribute, so you’re constantly working against that.”

So far, Williams seems to be winning the battle. Even so, he will tell you he never wanted to go into politics–despite his Harvard Law degree and his master’s in public policy from the Kennedy School of Government.

“I had always wanted to go into public service–not politics–as an official,” says Williams. “[I felt] I could have a real impact as an appointed official. All my [previous] jobs have actually been as an appointed official. I’m proud of that.”

Indeed, with his reputation as a tough budget and accounting manager, Williams carved out a public career that has included a stint in the federal government as the first chief financial officer of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. He also served as the deputy state comptroller of Connecticut and as an assistant director of the Boston Redevelopment Authority.

But it was Williams’ impact on the District as its chief financial officer that made him rethink the elective side of politics. Along with core staff members, he had led the city from a deficit to a large surplus. Though he’d initially resisted an effort to draft him for the mayor’s race, Williams changed his mind in hopes of completing the turnaround he’d set in motion.

Now, looking at the most political role of his career, Williams compares the job to running a restaurant.

“You’re personally doing the valet parking. You’re the maÓtre d’. You’re doing the cooking, the servicing, and the supplying, all at the same time,” he says. “You’re managing all these things, moving from an extraordinary level of detail up to an abstract level of policy, and back down to that extraordinary level of detail. Constantly up and down, all day, from eight in the morning until ten at night.”

The job has taught him something about himself. “I always felt I was a patient person, but I have found out that I’m even more patient than I thought.”

In his personal life, Williams lives up to his own health challenge. With such long workdays, he tries to carve out at least 30 minutes for himself. “That’s hard,” he says. “I try to get up in the morning and exercise. In this job, really the only time to exercise is in the morning.”

Williams also takes his mind off work with piano lessons, marking a return to the instrument he had studied as a child. “It’s deceptive because on the one level it’s very easy to play, but on another level–to really get back and master it–that’s hard. It’s going to take years, so that’s a great project.” The rest of his free time is spent with his wife, Diane, and their family.

Up on the Hill

The air-conditioned corridors of the Dirksen Senate Office Building at the U.S. Capitol offer instant relief from D.C.’s afternoon heat. Room 192 is filling up fast as Williams, City Council Chairwoman Linda Cropp, and two budget officials for the District take their seats at a table in the front of the room. Across from them is the wooden half-circle bench where members of the U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on the District of Columbia will hear about the city’s financial needs for fiscal year 2002.

Credit: Steven Rubin At the end of the day, Williams answers questions inside his office in Judiciary Square.

Williams is used to coming to the Hill on behalf of the District. Washington, D.C., is the only city in the nation that must get its budgets approved directly by the federal government.

Senator Mary Landrieu, a Democrat from Louisiana and the subcommittee chair, is at first the only senator to arrive for the hearing. She wants to proceed, however, and no one seems irked by the lack of senators in the room.

“What a personal honor it is to have you here,” Landrieu says to Williams and his staff. “You’ve done a wonderful job and had a tremendous impact in a short period of time.”

After a brief speech, Landrieu is joined by Republican Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison of Texas, who enters through the chamber door behind the Senate desk. She continues the praise for Williams. “I’m so excited about what’s happening in the District,” she says.

The two senators then open the floor to Williams. Sitting up straight and leaning forward to the microphone, Williams clings–for the first time all day–to a carefully prepared speech, a budget request that has been distributed to everyone in the room. He will talk for the next ten minutes about the gains the District has made in boosting its bond rating, increasing its reserve funds, and scoring clean audits for four years running. He asks for millions to improve housing, education, family services, and infrastructure. Then he sits back and listens intently as his staff gives a thorough breakdown of the budget by the numbers.

Williams and his staff are prepared for the questions of the panel. After 90 minutes, the meeting ends with the promise of a future hearing to refine certain details. But the subcommittee is pleased with the ways that the Williams administration has put the city’s shaky finances back on solid ground.

It is nearly 5 p.m. by the time Williams retreats to his 11th floor office in Judiciary Square to finish some business before calling it a day. The executive suite is tastefully decorated and highly polished, with a few hints of the mayor’s sense of humor. On one wall hangs a brightly colored print of a bow tie, which has become a symbol of all the ways Williams is different from the previous mayor. It also exhibits his defiance of the political foes who, in the mayoral election, tagged him with the moniker “Mr. Bow Tie.” Next to it is a framed official-looking form showing the final ballot counts in that election–with Williams the winner by far.

Even if he wins reelection next year, Williams knows he’s got a short amount of time to fulfill his goals for the city, thanks to a two-term limit instituted after Barry’s tenure. “I really only want to serve two terms, for a lot of different reasons,” he says. “Philosophically, I think, in the District, where we don’t have full representation, everybody ought to get a shot at the top job.”

Vision without action is a daydream. Action without vision is a nightmare. So goes a favorite Japanese proverb that Williams quotes often. It is also something he works hard to get his staff and city officials to live by.

“We try to combine a real vision with some real day-to-day, measurable action,” he says. “It’s slow, but it is happening.”